The wooden case is opened and inside, an array of tiny accoutrements. From it a tiny hat is removed while the credits sidle in, superimposed. And as a mouse figurine has her hair dyed vermilion, Paul McCartney's melancholic voice shepherds us through the opening titles for the delightfully downcast 2010 screwball comedy, Dinner for Schmucks.

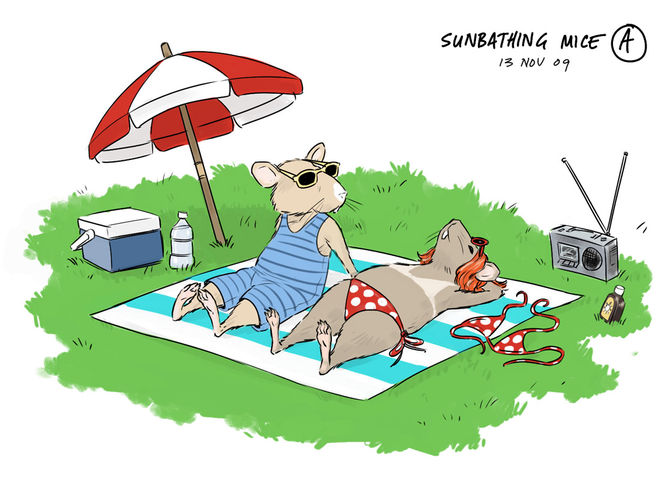

The song, "The Fool on the Hill," kicks off a journey through a series of close-ups of itty-bitty objects being selected, constructed, and assembled. The minutiae gives way to several astonishing tableau vivants of miniatures created by the Chiodo Bros., a trio of fantastically talented craftsmen who produce everything from stop-motion animation and puppetry to make-up effects and animatronics. In the opening of Dinner for Schmucks, a tiny bespectacled mouse and his redheaded mousette engage in the sweetest of romantic clichés, demonstrating an artistry so fine it leans toward obsession. The cherry on top is the whimsical and varied custom typography: the letters slink in and out of sight, vulnerable and idiosyncratic, wavering between wide and narrow, further lending the titles a sense of clumsy sensitivity.

Kyle Snarr at StruckAxiom on the delicate type design:

We wanted to create a naive type face that would feel done by Steve's character's hand without it being too precious or quirky. Likewise the animation had to tread lightly on the picture so as to support and not distract from the action on screen.

A discussion with Title Sequence Director, and Executive Producer and Co-Editor JON POLL, Storyboard and Concept Artist JOEL VENTI and Diorama Creators THE CHIODO BROS (Charlie, Edward, and Steve Chiodo).

Can you give us some background on how this sequence came about?

JP: This sequence sprang from the mind of the film's director Jay Roach as a way to introduce Barry, the lead character, without ever seeing him.

JV: One of the biggest problems that we had—and Jay was always thinking about this—was that we don't see Barry for about 20 minutes into the film. Then, he’s hit with a car and here he is with all of his mice and... is that enough? Do we need any character development earlier on and how do you deal with that?

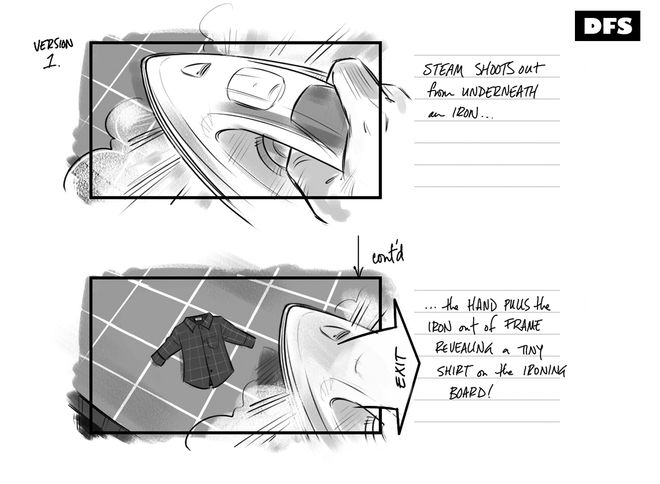

Storyboard examples

JP: And when we find him, he's an oddball: he's running across the street, he's got dioramas. I mean, this is a comedy and comedies always deal with things that are on the edge. But we're also supposed to love him. How do we get to that place? So the idea was that we would show, in the beginning, that he's an artist. It's all about the care that Barry puts in.

JV: At one point, Jay talked to Jon and I about an opening sequence that introduced the mice and Mouseland and in half a day I just worked out the storyboard sequence for what I thought Mouseland could be. It was already built, so I was able to look at it and look at the drawings and try to figure out how we could implement these characters. I did the whole sequence trying to show this unseen character building a Utopian world with mice. And if you follow the progression—because for me it's all about the story—it's all about building a character so that when we do see Barry later on we actually know a little bit about him.

We’ve seen him lovingly and carefully put together this world, build it from scratch. We’ve seen his little workshop, so you're getting a sense that there's a person here who really cares about this. And we're hoping that you make the link between his character, Barry, and the mice that we saw at the beginning of the movie. I'm really glad that Jay decided to do it because it turned out great.

EC: For us, Mouseland was the first look into Barry's world. The idyllic day in his life with his wife that he is now separated from. So from our perspective, the whole extension into the main titles was kind of an afterthought.

JV: Yup. Jay and I would sit there and he'd have me draw the different possibilities of what the mice could be. He kept saying, 'what would an idyllic life be like in this park setting? A day in the life of Barry and what he thought his life should have been like with Martha?' He's building up this relationship to what he wanted to have. And we see the longing, the sadness of love not fulfilled.

Diorama concepts

EC: What was really important to Jay was that connection between them. I remember going back and forth about the placement of the [miniatures’] hands in each others' pockets. That was a really intimate, touching little moment.

CC: Well, those personal mouse dioramas gave the character his heart. You connect with the guy, so he’s not just a wacky artist. He’s a sensitive, tragic character. And there were two levels of the mouse dioramas; one was a re-creation of the artistic masterpieces with mice in them from The Last Supper to the Mona Lisa to the American Gothic, and then there was the personal stuff from Barry’s life.

SC: The detail he put into the dioramas is the amount he would have put into the relationship.

Diorama example

So Edward, you folks worked on both the set piece dioramas and Mouseland?

EC: Yeah, we did all the mice. Everything that Barry is purported to do in the movie, we did. So the main titles, again, grew out of the Mouseland that was in the movie proper from day one.

CC: What was it, about 20 people that did the work of Steve Carell’s character?

EC: Thirty people did the work that Barry did in his garage. [laughter]

SC: In the beginning when we had our meetings with Jay and Walter Parkes, they wanted realistic mice. And then when we looked at a real mouse, we found out that they weren’t very attractive; they weren’t really endearing.

CC: Yeah, go to crappytaxidermy.com! [laughter]

SC: For the poses that they wanted us to create, the real arms weren’t long enough. They didn’t have any necks, so you couldn’t put a jacket on them!

EC: Yeah. Not enough shoulder, really.

SC: So we really had to redefine. They are realistic but there’s a characterization. No real mice were used or killed in the making of this.

CC: And real mice are smaller than what we created, because to get the tiny details of the hands and the fingers and the feet—a real mouse would have been impossible. So we suggested that we scale it up just a little bit to make it more manageable.

Mice set-piece details

EC: Yeah, it was very helpful. Real taxidermy wouldn’t have held up to the detail and the scrutiny that these things had to.

SC: I think the hands were maybe three millimeters long and two millimeters wide—very, very tiny.

CC: Well, there was a cuteness and an empathy that you wanted from them. If you filled the screen with a mouse face, it would have taken the essence of the scale away.

SC: It would be a King Kong mouse! It had to remain small relative to the frame of the screen. And actually even in the context of the dioramas themselves, there was an effort to make them smaller in the box so they didn’t look like giants. They were still mouse-sized within the environments. It kept them cute.

Finished mice ready for the shoot

JV: The taxidermy question gets brought up a lot. “How did you get the real mice to do that? How did you learn taxidermy?” The fact that so many people question that those mice are real is a testament to these guys.

EC: Well, them and the people we work with. A husband and wife team, Mark and Heidi Tyler, did all the fur work on it—amazing work—and then Joanne Bloomfield did all the wigs. Really an amazing team. We’re only as good as the people we work with.

CC: And how many mice were there all in all?

EC: Oh, I know. Absolutely. We made 121 mice.

Can you talk a bit about how the sequence was shot?

JP: I tried to shoot it as if everything was real size—not to treat it like a miniature. But it is very difficult to do that—it's the tiniest and most delicate moves. We were lucky enough to get the best dolly grip off the [first unit] and people liked working on it because it's a fun little sequence. So most of it—about three-quarters of it—was shot the first day. There are shots that we tried 8 or 10 takes where the tiniest little nudge that you would never see on a regular dolly shot would all of a sudden look like somebody bounced 30 feet, you know?

Title shoot on-set photos

Right. But that is part of its strength—the fact that it is shot that way, with dolly moves and tracking. Techniques that you wouldn’t normally see on something so small.

JP: Exactly! Normally that would be incredibly difficult to do; and it was sort of difficult to do! We did go back later because the movie had so many name titles. I think we ended up going back and re-shooting and getting six or seven new shots. Amazingly almost everything we shot made it in.

Is it all manual shooting versus a computer-controlled camera?

JP: All manual, yes. Just regular people working on the back of the main set, trying to shoot the sequence between first unit shooting, and trying to be quiet.

JV: Right. Even as it was, we found out when Jon and I were doing all the second unit stuff, you can only get so close on a mouse before some of the little hairs and details of the actual mouse doesn’t hold up on a huge theater screen. So we had to make sure that we never were more than a medium shot on a mouse. We didn’t do any ECUs on there or anything like that. It’s not anything against these guys, it’s just that you are dealing with a four-and-a-half-inch tall creation. They are beautiful beyond words, but you have to be careful when you are getting too close on them.

EC: There was a conversation of doing it in motion control, where you could reprogram and everything like that. But that was maybe a little too precise.

JV: And also with the motion control, we had potential problems in getting the lenses in the right place. We wanted to have more hand-held maneuverability with it, so we could make changes on the fly, instead of being locked into motion control because once it’s in, it’s in.

What was the process like for planning those shots?

JP: Joel, Jay and I would get together every Saturday during prep and work on storyboarding the movie, and while that was going on, [the title sequence] was always a part of it. And just like everything that gets storyboarded, you get there and you change things. Joel and I often went back and forth about what would work and then we'd go to Jay. He had just given me this great little Canon camera and I went in at six in the morning before shooting and I would just play with the set to work out shots. Probably three-quarters of the shots were predetermined on that little thing. Then ultimately the Chiodos would build everything that Joel had drawn and add to that. In fact, the opening of the title sequence with the work bench and the parts case...

Storyboard planning

Where we see the hands opening it?

JP: Yeah, and the dying of the wig. Those were things that we came up with especially to show the care, and when we came to shoot it, there was almost nothing from the main art department available. So, we asked the Chiodos to bring everything that they could carry from their workshop. The best example is the eyeglasses. I mean, they must have made dozens of pairs of eyeglasses for different mice. And there's that little wood dowel thing, and I saw that and I was like, "Oh, man. This is great! This is perfect!" It just seemed fitting that, here were these crazy artisans, the Chiodos, and we were actually using their elements in the sequence.

You guys are the real “Barrys” of the film!

EC: Yeah! It was unbelievable the amount of art that went into it, in terms of the reference material, the discussions, and in terms of the execution.

CC: I mean, the wardrobe and accessories were extraordinary. That was Mary E. Vogt.

She was the costume designer on the film?

CC: Yeah. Again, just supreme craftsmanship.

JV: And also Michael Corenblith, the production designer of the film, he was a big part of coming up with the environment for the dioramas, making sure that we were on task.

EC: Yeah, absolutely. He set the tone that was translated to Mouseland and evolved into the main titles.

CC: Yeah, just conceptualising with Joel, Michael was deciding what the spaces would be like, from the padded cell in the insane asylum to the destroyed mansion, to the colors of the books.

JV: And the color of the wood framing of the entire dioramas. I mean, every detail was thought of.

The finger-like monument

SC: And there was a meaning and a purpose to it all. A little anecdote that I remember was the finger sculpture that Joel had me working on. First it was a finger—just a sculpture of a finger. And then I started sculpting it, and then Joel was like 'Well no it's not really a finger, it's more like this'. And then it took me a while to figure out that it wasn't really a finger, it was a monument that happened to be finger-like.

JV: Yeah, I mean, the finger comes from that artist [César Baldaccini] who made the big thumb sculpture [in Paris].... So I wanted to show that Barry had a sense of art in some way, you know.

What about the titles themselves, the typographic treatment? Can you talk a little about StruckAxiom’s involvement?

JP: Axiom were great. They were already onboard creating the gallery artwork for the Kieran Vollard character, portrayed by Jemaine Clement, so they handmade the titles and did a whole bunch of type styles for us to see. They did a really good job of showing the handmade side, but that it wasn’t crude. I know there’s a temptation when you’re doing titles to get very flashy and I was glad that they knew how to fit right into it.

Type examples

So in terms of the time involved, how long did it take you to create the set piece dioramas and Mouseland? How long were you working on this?

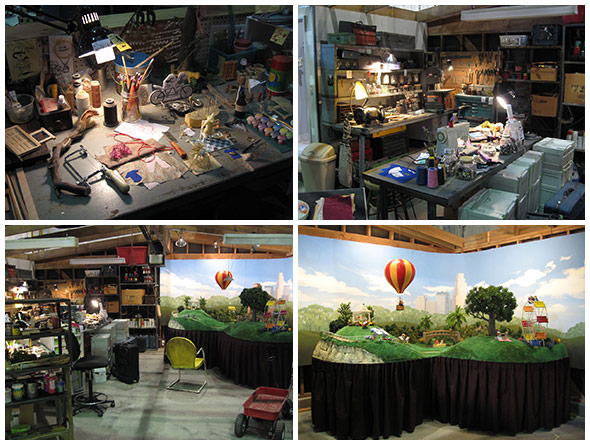

EC: We worked on the movie proper for about six months. To make all the pieces including Mouseland. And then we came back and worked another five or six weeks on Mouseland and all the other dioramas, and the extensions for the main title. So, that was probably a good two or three months’ worth of work.

How large was your team?

EC: We had thirty people come through the shop, on and off. Pretty consistently it was ten to twelve people.

CC: Every element was built from scratch. We had to have electronics and lighting put into each of the boxes. And we had a mechanical guy, and we had to have someone to actually make the wood-stained boxes.

EC: You know, we had to engage a pyro-technician to light the little tennis balls. We had to research what materials we could use to make the tennis balls and then light them on fire and still be convincing before they were lit.

CC: We had to fireproof the mice!

SC: The real issue was the hair. The hair styling. The red wig was a real challenge, to get the curl and the flip at that scale was a real challenge.

Chiodo Brothers studio staff

JV: I do want to take the opportunity to say that when you’re drawing this stuff you really aren't thinking about the ramifications of what you're coming up with. You're creating without accountability and these guys were so great in taking whatever I gave them and saying, "Let's figure out a way to make this happen." They were on board from the beginning.

SC: That was our job and that's our challenge. When we see a board that we think works really well—a beautiful drawing that expresses something—it's our job to create that in three dimensions. Like the little turntable, the spinning wheel, you had Barry just touching it with one tiny little finger hanging on, so it was a challenge to create a model that would have the mouse's little arm suspended on his finger on that one arm and then also have it spin. It was a little mechanical challenge there. And we did it and it was great.

CC: By the way, thank you, Joel, for that crystal chandelier that had to be made.

JV: Yeah, I'll take credit for that. You can't buy those in the store. You had to make every little crystal! See, that's the stuff that your readers and people who watch the film never know the full extent of—the real love and care that goes into every detail. So yeah, if the chandelier didn't exist they had to make it themselves and I think Ed said this to me at one point, "If you draw it we can make it." And that gave me the freedom to design whatever I wanted, whatever Jay wanted.

CC: Yeah, but you took it literally! [laughter]

The Spinning Wheel

How does this compare, in terms of the amount of detail and craftsmanship that was involved, to other projects that you’ve done?

EC: For us, it’s right up there in terms of the art. The only thing that would maybe rival it would be something like Team America, where again, the movie was about the art, the precision, the execution, the puppets, the wardrobe…very similar, in fact. It’s the same discipline.

SC: Yeah, the level of artwork that was required is about the same. It was just consummate, perfect art.

CC: This one was smaller than Team America. What saves it in terms of the scale is that we didn’t have to make every little piece. We were able to buy some tables and chairs and modify them. So it saved us a bit of work.

EC: But the big difference in Dinner for Schmucks, was the respect given the art. Everybody in production, the producers, everybody understood and respected the art, and I think the audience respects it as well. Overall, people really respond to it and they appreciate it. And at the end of the day, that’s what it’s all about.

And how did you feel about the music that was chosen to go with it?

SC: We were very pleased. It really showcased our work like never before. Thank you Sir Paul!

The Chiodo Brothers workshop

How much of your work comes back to you after a film has wrapped?

EC: It varies on the production. On something like Schmucks, they own it so we get very little back. On other projects, on a lower budget thing, we get to keep a lot of stuff because it’s assets that we’ve reused from our stock, so we maintain it. But, on something like this it’s all gone.

Where are all the mice now? Mouseland and the dioramas? Are they in your workshop?

CC: Like in Indiana Jones, they’re all in a crate at the back of a warehouse. Maybe not all of Mouseland, but the terrain itself is probably in a warehouse someplace. The individual boxes, I’m sure some executives have them.

EC: Actually they’re all in Paramount storage. Rumor has it that Paramount is opening up a museum on the lot and they hope to display them there. The Tower of Dreams will live someday and hopefully Mouseland as well.

JV: You know, The Tower of Dreams was actually on display at the Arclight theater in Hollywood for a couple of weeks, which was pretty cool to see. It gives the audience an opportunity to see the dioramas in real life.

So I have to ask, where are the Killer Klowns?

EC: The Klowns we have. [Edward shows us a display case in his office]

SC: There they are!

Oh wow! Are they ever going to make a comeback?

EC: Uh, yeah. You know, we’re in the process of doing some kind of sequel. We just have to wait for the… money.

CC: The money!

Yeah, it always comes down to that in the end.

Mouse couple

LIKE THIS FEATURE?