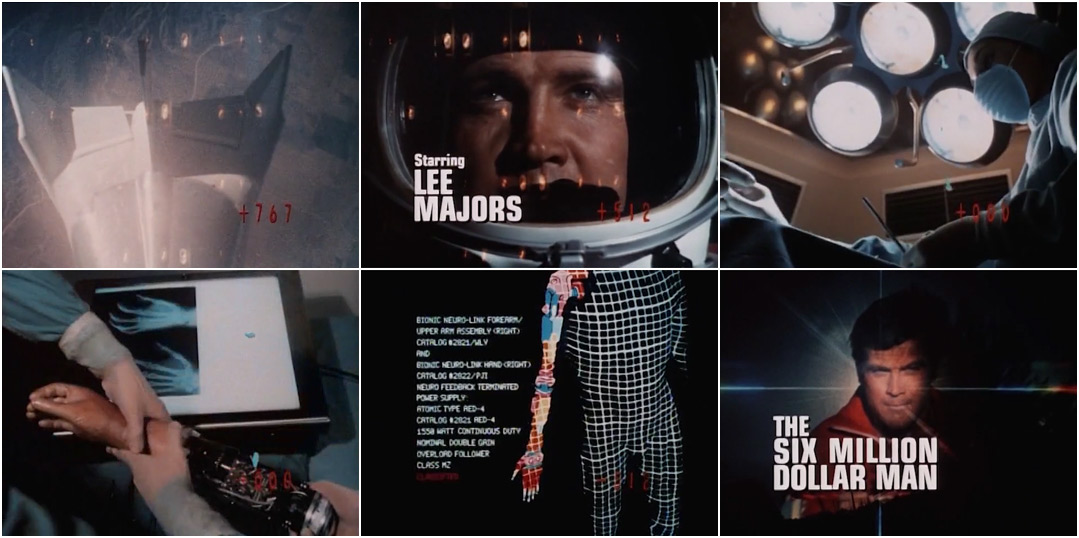

A horrific accident, a life-altering surgery, and one very expensive, very suave superhuman add up to one of the most memorable title sequences ever created for television. It's The Six Million Dollar Man.

To create the show’s opening, Universal looked to stalwart title designer Jack Cole, whose previous work for the studio included intros for TV shows like Ironside and The Name of the Game. Unlike Cole’s other sequences, however, the main titles for The Six Million Dollar Man needed to perform some narrative heavy lifting if the show was to succeed. In just under 90 seconds, the opening had to recount not only how Austin became the titular cyborg, but it also had to communicate the very nature of bionics to an audience who, at the time, was largely unfamiliar with the concept.

JACK COLE on the role of the title designer from the short documentary An Iconic Opening featured on The Six Million Dollar Man: The Complete Series DVD collection:

There’s a major misconception about what we do – everybody thinks we sit around picking out typefaces and that’s the beginning and end of it. The truth of the matter is we create the opening sequence of the show. We create the texture, the backstory, the visual quality that is going to follow in the show. So we have a lot of things to do and also have to hook an audience into watching the show.

In The Six Million Dollar Man, that hook takes the form of the explosive plane crash that set the stage for Austin’s bionic transformation. First depicted in the 1973 TV movie of the same name, again in openings of the telefilms Wine, Women and War and The Solid Gold Kidnapping, and then the series proper, Austin’s ill-fated flight was not a special effect, but instead an assembly of archival footage from the real-life May 10, 1967 crash of the Northrop M2-F2 and flights made by its successor, the HL-10.

NASA/USAF lifting body test flight footage

Developed by NASA and the United States Air Force, these experimental wingless aircraft called lifting bodies (used interchangeably in the sequence) were actually precursors to the Space Shuttle, making Austin’s fictional title of astronaut quite apt.

Part of what makes the inclusion of the M2-F2 crash in the sequence particularly fitting, though, is the fact that the real-life accident served as a major inspiration for author Martin Caidin’s Cyborg – the novel on which the TV series is based. Caidin, both a writer and pilot himself, actually witnessed the 1967 crash that nearly killed test pilot Bruce Peterson.

The injuries sustained by Steve Austin in the opening were not unlike those that Peterson himself suffered when his experimental craft plowed into a lakebed near present-day Edwards Air Force Base. Peterson, however, eventually lost sight in his right eye as a result of the accident. He went on to have a long and successful career as a pilot before his death in 2006. He is said to have disliked seeing the M2-F2 crash replayed on television so often.

Test pilot Bruce Peterson and the M2-F2

To flesh out the crash montage, Cole intercut the archival footage with shots of series star Lee Majors inside the real HL-10 cockpit. These shots were then overlaid with various elements, including blinking computer lights, flickering numbers, and a frantically sweeping radar display. To simulate the “squeeze and static” of Austin’s communications with the control tower, Cole had Majors record all of his dialogue through a real flight oxygen mask that had been rigged with a microphone. These audiovisual effects were added to make the sequence appear as though it was a computerized recording of the accident and, more generally, to ramp up the feeling of tension.

Lee Majors shooting scenes in the HL-10 cockpit

At this point the title sequence moves into Austin’s transformative and life-saving surgery. The disembodied voice that introduces the wounded astronaut as “a man barely alive" is that of Six Million Dollar Man producer Harve Bennett. As schematics of Austin’s bionic upgrades flash across the screen, Bennett’s narration is supplanted by actor Richard Anderson’s now-classic refrain: “Gentlemen, we can rebuild him. We have the technology. We have the capability to make the world's first bionic man. Steve Austin will be that man. Better than he was before. Better... stronger... faster." This monologue would later be shortened significantly for syndicated versions of the show.

While Austin’s limbs and eye are replaced by bionic upgrades, the crippled pilot’s vitals are put front and center, heartbeats displayed as spikes and waves on an electroencephalograph machine. The prosthetic leg used during the surgery montage was actually a heavily-modified hand-me-down prop created for the 1971 Civil War drama The Beguiled, where it doubled as actor Clint Eastwood’s amputated limb. Cole himself makes an appearance during this part of the sequence – it's his hands that pass one of the bionic legs to the surgeon. Though footage of Austin’s operation was created specifically for use in the series’ title sequence, certain elements were eventually edited into the syndicated version of The Six Million Dollar Man pilot in order to maintain continuity and to enhance the original scene.

The 2011 documentary An Iconic Opening from the The Six Million Dollar Man Season 1 DVD

The finale of the sequence features Steve Austin back on his feet and in full Bionic Man mode, running on a treadmill, running through a field, and running towards the camera like it’s his damn job. Although it was actually sped up, the shot of Austin sprinting alongside the white fence is a rare instance of his superhuman abilities being depicted at so-called “regular” speed.

For the concluding shot, Majors was filmed using high speed cameras. By slowing down this footage and overlaying it with fast moving images, Cole and the producers hoped to evoke a feeling of great speed and power as Austin basically ran into living rooms across North America. According to Harve Bennett, who got the idea from watching NFL sports documentaries, the title sequence was the first time that Austin’s powers were portrayed in such a way. The slow-motion effect became the guideline for how the series would depict bionic powers in action and ultimately became one of the show’s hallmarks.

Title Designer Wayne Fitzgerald's main titles from the 1973 Six Million Dollar Man TV movie Wine, Women and War

Cole’s Six Million Dollar Man title sequence is certainly an iconic piece of design and the intro that most people associate with the show. However, Cole was not the first designer to take on Steve Austin. That honor belongs to legendary title designer Wayne Fitzgerald, who created the opening and end titles used in Wine, Women and War and The Solid Gold Kidnapping – two of the TV movies that preceded the series.

Fitzgerald’s intro begins not unlike Cole’s effort – highlighting Austin’s aeronautical exploits, accident, and augmentation – but it quickly takes on a slightly goofy, James Bond-esque tone. These titles also featured a truly insufferable theme song, courtesy of singer Dusty Springfield, which was thankfully not used for the series.

LIKE THIS ARTICLE?