“You gotta keep moving.” This is the advice that Pablo Ferro’s grandfather gave him about avoiding scorpion stings when he was a boy and a code Pablo has ascribed to throughout his life and career. But Pablo did get stung – and it nearly killed him. In Part Two of our feature interview with the legendary title designer and his son Allen, we delve deeper into the man behind the legend.

Make sure to read Part One of our interview with Pablo Ferro

As a young man, Pablo gravitated to comics, moved over to animation, and quickly became one of the most well-known and sought-after commercial and title designers of the last 60 years. After all, his ethos is based entirely on motion. Exploring ways to imply it, to create it, and to innovate with it would become the foundation of everything he produced.

During the ’60s, Pablo collaborated with director Stanley Kubrick on the trailer and titles to the uproarious Dr. Strangelove, and with his agency Ferro, Mogubgub, and Schwartz, designed and executed numerous commercials. While working on Norman Jewison’s 1968 film The Thomas Crown Affair, he pioneered a multiple screen technique and became friends with actor and “King of Cool” Steve McQueen.

We begin part two at this juncture: Pablo and McQueen reunite to work on Bullitt, Pablo travels to the UK to once again work with Kubrick, this time on A Clockwork Orange, he returns to New York, and has a harrowing encounter with a hitman.

Part Two

So, in 1968 you were working on the titles for Bullitt. How did that come about?

Pablo: That was because of Thomas Crown Affair – Steve McQueen loved me. He said I had to come to San Francisco, to give him an idea for a title. I said, “Okay, I’ll give you a month.”

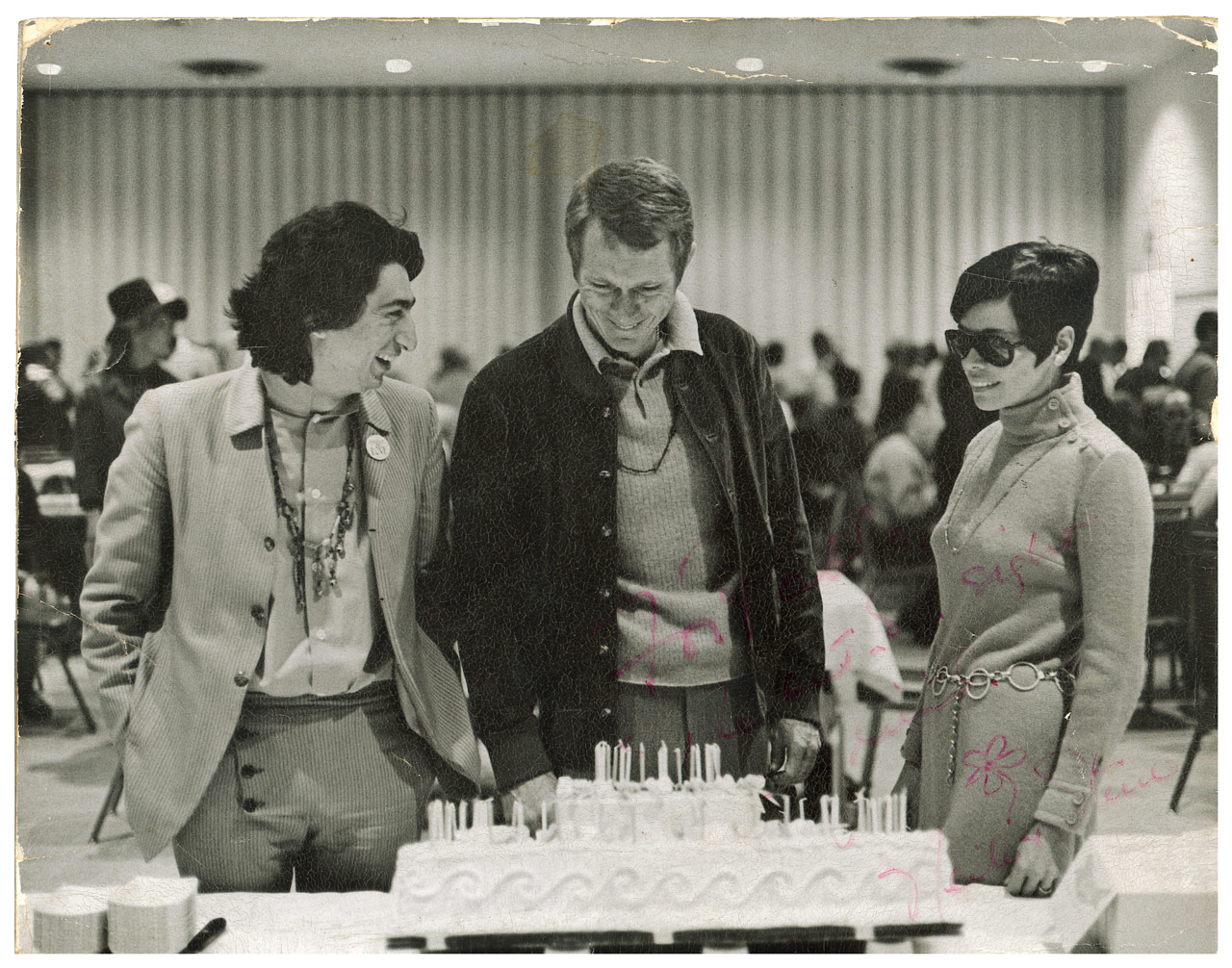

Pablo with Steve McQueen and Neile Adams, 1967

Steve got me a great place in San Francisco overlooking the bay. It must have been a week or two, and the idea came to me. I took a black and white photograph and I cut out the word “Bullitt” and I got Steve to come over. We went outside and I got this car and moved it into his eye, into one of the letters. In his eyes all he saw was color and he said, “I love it. Let’s do it.” I never got such a fast reaction to an idea!

He was great – he just knew. Me, I didn’t know – it was just an idea. Again, that was something that I just kept moving. And in those days you would always get a jump in one of the movements.

The titles had a story to tell. My instruction [to Director Peter Yates] was to move – never stop the camera unless there was something that you wanted to see move. And they did that. Peter Yates did exactly what I had in mind. It helped. The lettering is also moving so it creates another design completely, which makes it very interesting – and it's very simple, when it's moving from right to left.

Allen: It doesn’t interfere with the story. In fact, it aids with the storytelling in the narrative.

Bullitt main titles (1968)

Were you involved in shooting the interior and exterior location shots for Bullitt?

Pablo: I couldn’t do it because time ran out and I had to work on other jobs. I did shoot one shot where they needed to show Chicago so I went to Chicago to this hotel balcony by the Chicago Sun-Times building.

Oh, the opening.

Pablo: Yeah, the first shot. We did two or three takes and that was it, we left Chicago. The next day was the Chicago riots. If I had stayed another day I would never have gotten out of Chicago. Luck was on my side, you know.

How did you composite the title sequence, given the tools you were using at the time?

Allen: It’s multi-pass opticals.

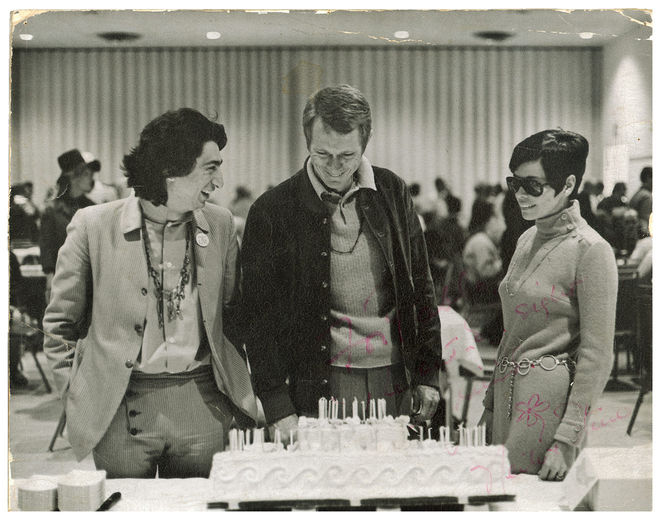

Actor Robert Vaughn, Pablo Ferro, and Allen Ferro at a Bullitt tribute screening, 2010

Pablo: Those shots that go through, we did it twice, one with a matte, with black all around the lettering. Inside the lettering, you have an image and that image stays there as you go through it, then you go back to your black and white image outside.

Allen: He had to look at the dailies, to time them, plot where the text is going to go and how it’s going to move. He edited the sequence first.

Pablo: They assembled one that was pretty good, that told me everything. The editor was very good.

Allen: But that’s the process: you look at it, you take your text, you plot your move.

Pablo: Also, at that time, you had to match – you had to do a tiny image to a big image – so you had to have different passes and the camera could only move so far and then you had to match that movement so that you could continue. If something goes wrong, you get a click, you jump. You gotta do that optical quite a few times before you arrive.

Now it’s a different story. When I did To Die For the artwork is a circle to the picture to the dots. We did it on the computer.

To Die For main titles (1995)

It looks like one piece of art but it was many pieces! It is the same as with Bullitt, only with Bullitt we had to do it twice: once black and white and once for the color. Happy things would happen with the lettering, because the background is moving and the lettering was moving also – unexpected things happened. That's extra, thank you!

I started those titles in San Francisco and I finished in New York, sending it to Peter Yates. He wanted me to come back to Los Angeles and live there. I said, not again! Another Stanley Kubrick.

Allen: The one thing I learned from my father in this kind of two-dimensional-meets-three-dimensional world is that you do have a timeline, but you can work within that timeline to utilize what you have, you know? If it's 24 frames per second, yes, you could turn 24 frames per second, but you could also lengthen the scene, you could hold frames – there's all kinds of trickery to create an illusion. That's really what he specialized in. That's why the animation is such a large component of the creative process here. The process of understanding layout. Otherwise you can't see anything, you know?

Pablo: And when you go frame-by-frame, it's a timed exposure, so you get the image much better than usual, because sometimes you have to change the exposure in every frame.

Citizens Band (aka Handle with Care) main titles (1977)

Allen: Yeah, you look at Citizens Band and that's a great example because it looks like it's live – like a live dolly shot – but it's all animation.

Pablo: Yeah, the reason it looks like it's live is because it's three-dimensional objects that are moving. When I put that in the animation stand, I put the hole in the middle and I placed the CB and lit it. That one had a motorized animation camera, the first one. And that's frame-by-frame exposure. I call that the “silent cut” because you don't feel it. By the time you're in a new scene, the cut went by already and you didn't see it because everything is exactly the same speed, so the thing that makes a cut jump is changing the speed. Here it's exactly the same, so it's smooth.

We’re so used to computers now, but for certain things you get nowhere near the same effect as if you're actually shooting live, whether it's frame by frame or in the studio.

Pablo: Yeah, and if I shot that with a regular camera at 24 frames a second you wouldn't get the image so sharp. That's what made it even more interesting. All of a sudden you're seeing something that is sharp, not soft. And that's the time exposure.

So Bullitt was ’68 and then in the ’70s and ’80s it seems like your work was more focused on main title design or logo design as opposed to the whole sequence.

Pablo: Well, it was always mixed. Sometimes I would do a montage and then end up doing the titles.

For Midnight Cowboy (1969), I did the montage for the television set changing channels while they're on the bed, in the bedroom scene. The remote control falls on the bed and [Sylvia Miles as Cass] falls on top of it and Jon falls on top of her and then the channel changes.

Midnight Cowboy (1969) TV sex montage

And then they wanted me to do the main title. I looked at it and I could see it really needed some new shots because the director, John Schlesinger, had shot multiple long shots and it was just okay.

So I went to New Jersey and shot all the close-ups. The camera assistant was the same size as Jon Voight. John Schlesinger came in while I was shooting and he said, “Pablo, I think he's holding the radio in the wrong hand.” I said I don’t think so, flipped out a clip, and said, take a look at this, tell me what it is. He said, oh, all right.

Allen: Yeah, he’s very meticulous about continuity. Is this where you met Harry Nilsson as well?

Pablo: Yeah. After that, John just left and said see you later. Harry Nilsson was trying to sell his song, “Everybody’s Talkin'.”

Midnight Cowboy main titles (1969)

The Tumultuous ’70s

Richard Greenberg is a title designer and a co-founder of R/Greenberg Associates, now R/GA. Early in his career he worked for Pablo Ferro as a PA. Read his amusing anecdote about this job, and much more, in our feature article R/Greenberg Associates: A Film Title Retrospective.

When we talked to Richard Greenberg, he mentioned working for you and your brother as a PA in the ’70s. Do you remember that?

Pablo: I tried to forget, it was not a very good experience.

Allen: With Richard Greenberg?

Pablo: No, with my brother. It was in the early ’70s. Sometimes I would give [José] some work, but he wasn't on staff. He was not a very good person. And people caught on right away because even though he sounded just like me on the phone, he did terrible things to people.

We don’t have to discuss him if you’d rather not. You moved from New York to LA in December 1979, right?

Pablo: Yeah, I left in December ’79 and I changed the company name. I didn't want to use “Ferro” for a long time because of the situation with my brother.

—Pablo FerroI didn’t move fast enough to close the door.

Allen: There is a back story. José, Pablo's brother, had acquired the company surreptitiously – he took it over – so there was strife. This all started with an incident which turned out to be almost a home invasion. Pablo was injured.

What year was that?

Pablo: It was 1970 I think, January 12th. What happened is, a hit man came to my door and it was the wrong door.

Allen: Let me explain. Pablo had a brownstone on 2nd Avenue in Lower Manhattan, a factory loft with 5 stories, that had apartments starting with Apartment A on the ground floor. Pablo was in “1A” on the second floor, above Pablo were friends of his in 2A, a couple. Above them, apparently, were bad guys or drug dealers and they made so much noise that they drove my dad’s friends crazy. Later, my father found out that they had called the drug dealers up and said that the police are on their way and so they cleared out.

Then, this guy shows up to my father’s apartment and tries to shoot him. The apartments had fire doors so they were full-on metal doors and the guy probably shot a .38 or .22. When my dad opened the door, the guy looked very pensive, thinking, wait, you are not the guy? But he shot anyway. The bullet hit the door and then hit my father.

Pablo: He was pointing the gun at me when I foolishly opened the door and his hands went up because he already pulled the trigger. It hit the steel door and ricocheted and got me in the neck. I didn’t move fast enough to close the door.

Allen: Which is another miracle in itself because my father was completely paralyzed and he completely rehabilitated himself. He was able to do that and then work later on.

Pablo: So I took a year off.

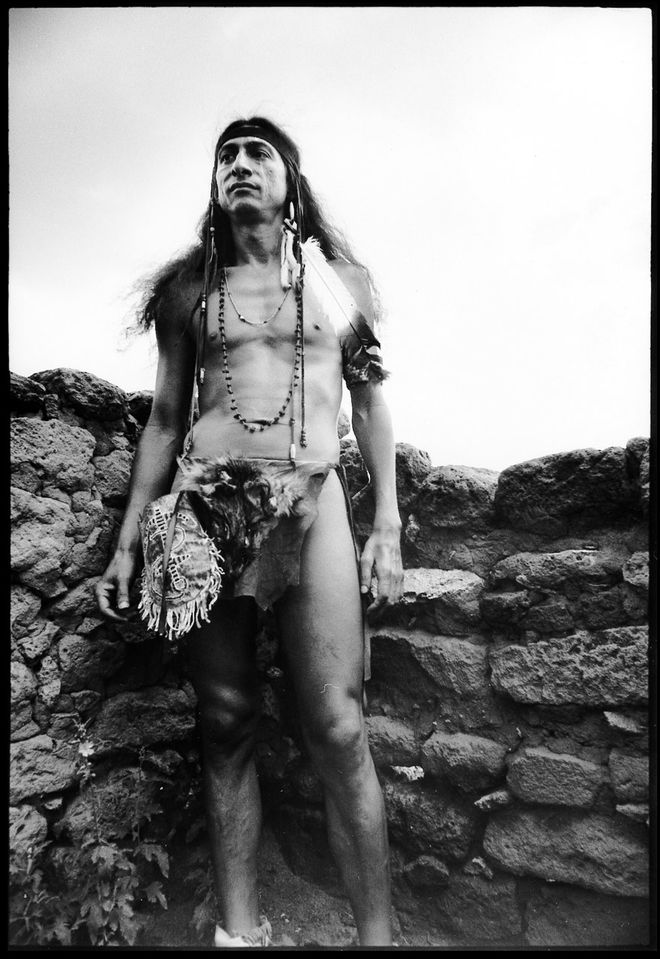

Pablo as the 'Indian' in Robert Downey Sr.'s Greaser's Palace (1972)

And then José took over the company?

Allen: José took advantage of the fact that Pablo spent months in the hospital recuperating and drove it into the ground. But it got worse, because he started saying that he was Pablo.

Pablo: People got wise that it wasn't me and wouldn't give him work and he was doing very badly.

After a year, I was back in pretty good shape, and it was about that time that Bob Downey [Robert Downey, Sr.] asked me to act in Greaser's Palace.

When I finished Greaser's Palace, Bob Downey and I went to visit Hal Ashby who was working on Harold and Maude. They asked me if I wanted to work on that and I said sure, so I stayed.

A Clockwork Orange (1971)

Let's talk a little about A Clockwork Orange. You went back to the UK to work with Stanley around that time, right?

Pablo: Yeah, he called just at the right time. I said sure.

Was this another marketing campaign, including the trailer?

Pablo: Yeah. I asked him if he had any shots that he would like to use for the trailer and he looked at me and said, “Why ask me, Pablo? You're doing it.” I said okay. He let me go along until I finished it and when I showed it to him, he said that’s great man, that is better than the film. I said no, this is just a bit of the film. The film is great.

Allen: One thing that I found amazing – I found this out recently, too – was that Pablo used only dailies because Stanley doesn't let his negatives get touched.

Pablo: Yeah, he does a lot of takes so I had a lot of choice. I took the best outtakes which look very much like the takes he used. For the Clockwork trailer, it’s all outtakes.

A Clockwork Orange trailer (1971)

How did you come up with the concept? The typography and the music?

Pablo: The music influenced me. I love all the music. The rape [scene] music was beautiful. The overture alone. What he did, he sped it up so it’s a version of...

Allen: "The William Tell Overture," which was used for the orgy scene. Malcolm gets these two girls in a mall or a store and drags them in...

Pablo: I forgot all about that and I also sped it up a bit more. The music was telling me what to do. I liked the lettering and the posters with the girl. I took those pieces and made a graphic movement with the live shots. Usually I don't work with music, I'd put that in later, but this one you can’t do that. So what I did was get a grease pencil and play the music on the Moviola and mark all the beats.

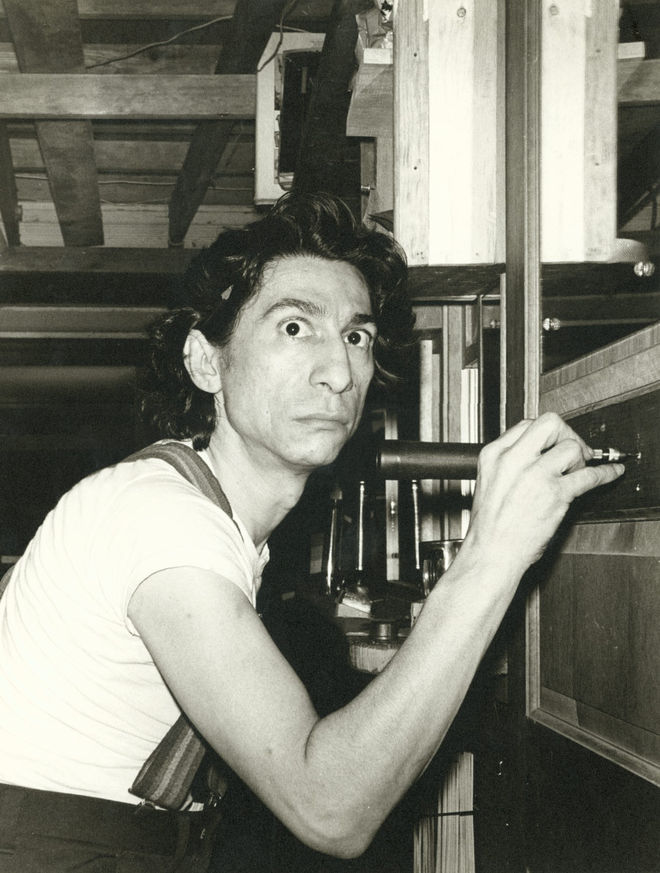

Pablo laying out a credit screen at his 2nd Ave. apartment/studio, 1972

Allen: You put on the synchronizer, yeah. It’s amazing. I’ve seen him do it many times.

Pablo: I did it like that – here, I would only have 4 frames, here, I could do 8 frames. But it was tough to do, trying to cut that fast. The cut had to match the next cut, it can’t jump. You have to go slowly so the images will get you to the left side and to the right side. I must have learned the entire film like an actor learned all his lines.

Allen: I haven’t seen a trailer like that since.

Pablo: I didn’t know how to end it. It just never stopped, so, boom! I saw it with an audience and they all reacted to the cut.

Allen: [laughs] Music and all, it just cuts! It’s hilarious! It’s so serendipitous.

Pablo: I had double takes on it because it would rip in the Moviola! It’s very hard to do, that one.

Allen: On film, anyway.

Pablo: Everybody imitates work that I've done, but for that one I haven't seen an imitation yet.

Did you also do the main titles, the different colors that appear in the front of the film?

Pablo: No, no. Stanley did that.

Main title stills from A Clockwork Orange (1971)

The End of Pablo Ferro, Films

What happened after Clockwork?

Pablo: When I came back I went to the loft and the door was sort of half open, and I see a policeman there and guys with suits. I said, "What are you doing here?" He said, "Oh, we just got to get all this stuff and put it in the street." I said, "What do you mean?" They said, "No rent has been paid here for several months."

Pablo at his 2nd Ave. studio/apartment, 1975

I mean, it was pretty scary because if I was there a day later my stuff would've been on the street. But I called José up and I said you'd better get somebody, I don't know how much is owed, but you'd better get it to me right now – and he did. That was the end of the relationship.

He tried to pull a fast one by calling it José Ferro, Films with the same type that I had so people would think that's me.

Allen: That's why Pablo basically changed his working name to “De Pablo, De Pablo” because – it wasn't really paranoia or anything – but José was running around New York saying that he was Pablo. The relationship sullied everything.

Can you tell us about Zardoz (1974)?

Allen: It really shows the creative process of how Pablo thinks visually. It is a visual thing always – it is always a visual solution that comes out of his mind. If he can think it, he’s going to damn well do it, with film, or paper, or a sculpture. With Zardoz, there was sculpture involved.

And how did you film the trailer?

Pablo: I got this special lens that was used for a spotlight. And I filmed the artwork through that. I like to do light effects more than optically put it together.

Allen: What Pablo’s describing is that he found this lens which really was – when I look at it now it’s a focus lens for a high intensity light – like a spotlight. But he found this lens and he used it on the optical bench for Zardoz.

What about the actual design, the lettering that’s seen in the trailer?

Pablo: That was done by the studio.

Zardoz teaser trailer (1974)

It was around this time that you moved to California, right?

Pablo: Yes. In 1979, it was around December I think. I couldn’t take the cold anymore! It was too cold and humid. I needed a place where it was sunny.

CONTINUE on to Part Three, in which Pablo moves to LA, partners with Hal Ashby, works with The Rolling Stones, and moves into the digital era. He speaks about his work on The Addams Family, Men In Black, L.A. Confidential, the experience of updating a Saul Bass design, and his upcoming projects.

Special thanks to Allen Ferro for his assistance in researching this article.

Support for Art of the Title comes from