If you could create a world of your own, what would it be like? Would you roll back time, would gravity exist? Would you take advantage of the infinite possibilities before you?

Sally Cruikshank’s animations delight in those possibilities, pushing beyond standard notions of how cartoons should look, move, and sound, unleashing a flock of bizarro creatures and their bold accoutrements. With her award-winning 1975 film Quasi at the Quackadero, Cruikshank created a surrealist gem of unearthly landscapes and outrageous characters. The film earned her international attention, an entry into the National Film Registry, features in books with the word “Greatest” in their title, and spots in major museum exhibits.

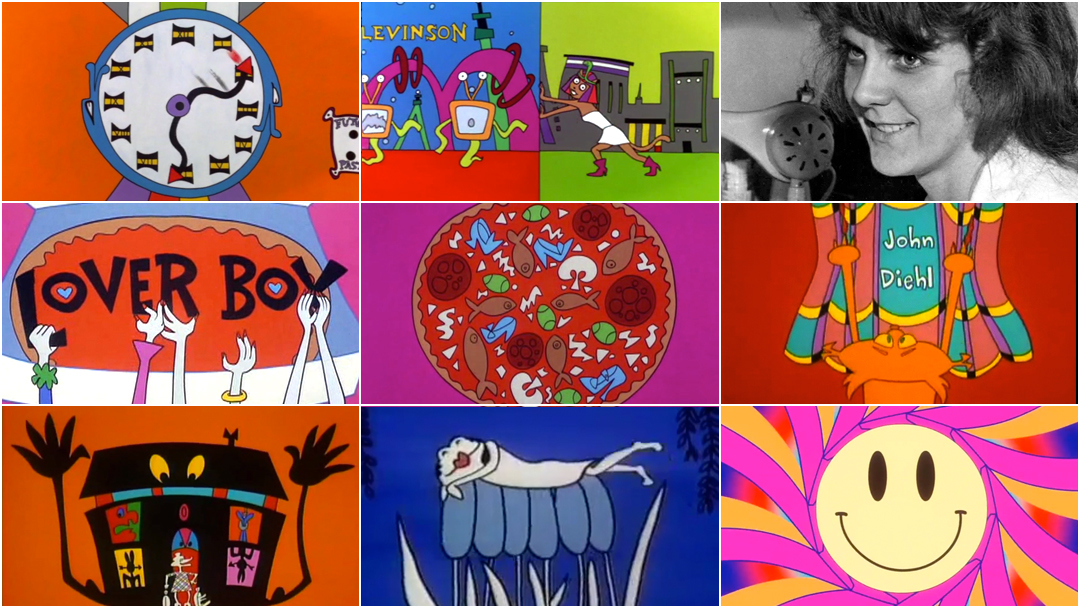

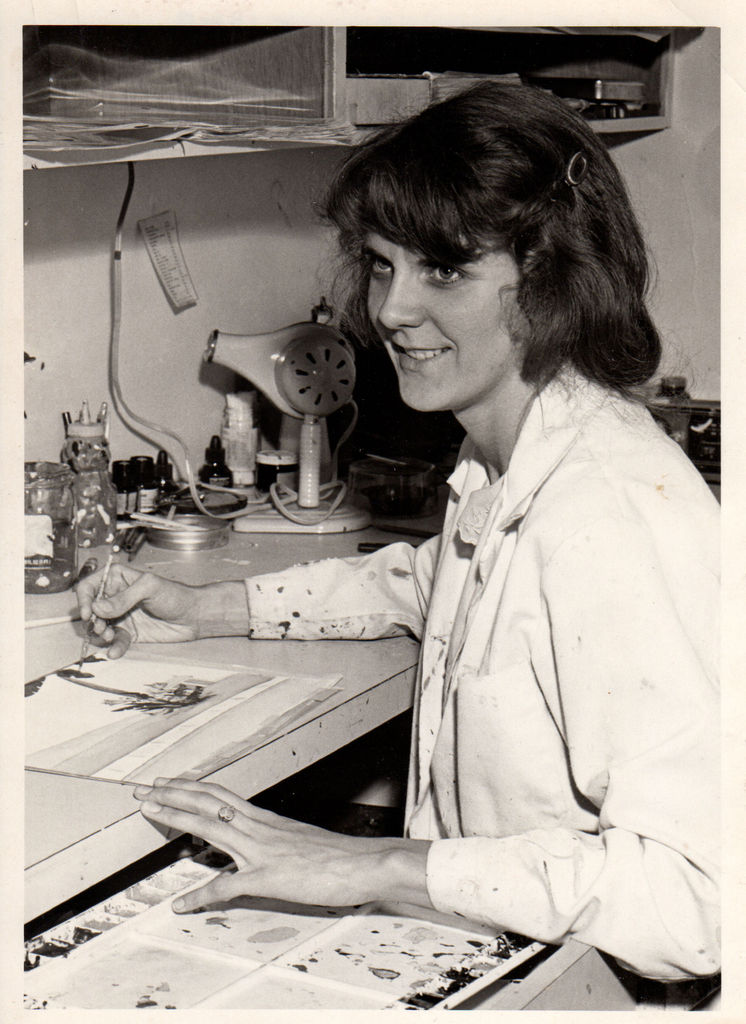

Sally Cruikshank at Snazelle Films, 1978

After Quasi came several more shorts, a number of innovative commercials, and Hollywood. Throughout the ’80s, Cruikshank found herself being courted to create opening titles for major motion pictures. Her first, Ruthless People, opened the door to others. In each of her title sequences for Mannequin, Loverboy, and Madhouse, Cruikshank leads viewers into weird and wacky territory. The credits are dismantled, dismembered, and done away with. In a flurry of Memphis design and greed, Ancient Egypt, aliens, and Philadelphia, love, lust, and anchovies, and houseguests gone awry, Cruikshank weaves a series of journeys loaded with narrative clues, historical references, and hilarious gags. Soon, however, her talents were snatched up by Sesame Street, a veritable dream job for animators of the time, where she stayed for more than a decade.

As the ’90s slowed their roll and the Internet began to gain momentum, Cruikshank saw an opportunity. She learned Javascript and PHP, Flash animation, created sassy interactive games, and experimented with cartoons for mobile phones.

Throughout her career, Cruikshank’s evocative work has been a door to fantasy, to radiant visions on the edge of dreams, to worlds both past and possible. In experimenting with the bounds of imagination and humour, Cruikshank took to any medium available to her, from cel to film to digital to code, and pushed its buttons.

Have you read Part One? Read Sally Cruikshank: A Career Retrospective, Part 1

To be a formidable cartoonist and animator, one must build a world of one’s own. Sally Cruikshank does just that.

In Part Two of our two-part feature interview with Sally Cruikshank, we dive into her film title sequences, her animations for famed children’s show Sesame Street, her pioneering experiments in interactive digital art, and her advice for animators working today.

So, you had just wrapped up some commercials and your first title sequence project, for Ruthless People. We're still in the late ’80s. What came next for you?

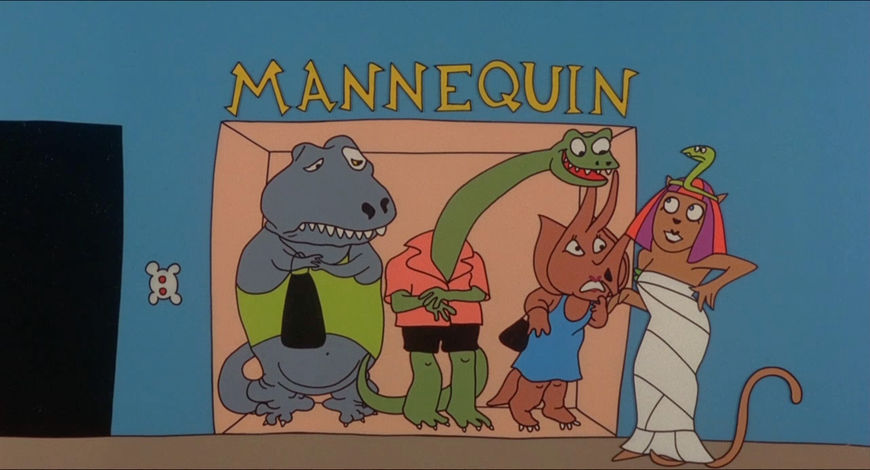

SC: I think it was Mannequin! Yeah. I still have all of the storyboards. They’re very pretty. I would do them in an 8.5x11 format, which isn’t usually how people did storyboards, but it made it easy to Xerox.

I saw the movie and I didn’t think much of it. I believe it was the editor who brought me in, Richard Halsey, and they had a problem. They were aware that they had a problem in their story. They had to get the main character, the mannequin, from Ancient Egypt to modern-day Philadelphia, so they thought that the animation would help cover for this gap in the story.

Image Set: Original storyboards by Sally Cruikshank for the opening title sequence to Mannequin (1987). The main character travels from Ancient Egypt to modern-day Philadelphia, meeting a slew of interesting characters along the way.

It’s not the best way to be doing animated titles – ideally they’re just going to warm up the audience and have them feeling good and then the movie begins, right? Not struggling through getting the audience through all that time! So I pictured it as being… Well, originally I was going to have the sequence be more about this little elevator operator who features in the film, where he’s taking [the characters] to different floors and there’s a different period of time on each floor, but that doesn’t… you hardly grasp that with what’s going on.

They had hoped to get the song “Walk Like an Egyptian,” which would’ve been really great, but they couldn’t get the rights to it so they got Belinda Carlisle to record “In My Wildest Dreams.”

Mannequin (1987) main titles designed by Sally Cruikshank

Apparently, this is a song that you can’t get now! That movie was so popular for people of a certain age. I could never understand it. And there’s no version available of that song without the stupid sound effects on it that are in the titles. This was the only thing that I had a disagreement about – the sound effects. I don’t like sound effects done like that – boing, boing! – it was an old fashioned style of sound effects. Doesn’t go well with the song.

Yeah, it’s a bit cheesy, right?

Cheesy. Yeah. That’s a good word for it.

Did you work with Ted & Gerry Woolery at Playhouse again for this one?

Yes. I think for most of these titles I did, yeah. I think that was followed by… Loverboy, which I have almost no memory of because I was pregnant at the time! Ted and Gerry probably took over at the time.

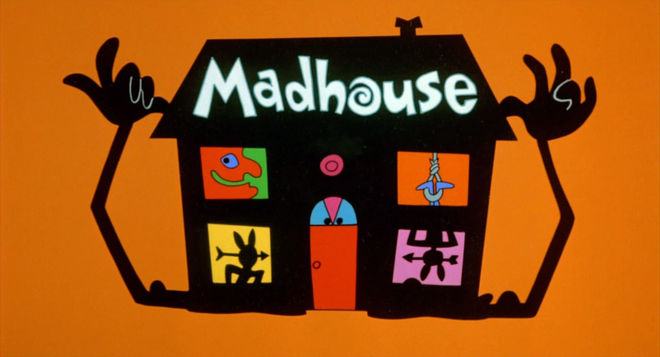

No, wait, there’s Madhouse! Madhouse came before that.

I looked at those titles today and I thought, you know, I like this. This one was one where I liked the song. “Let’s Dance” by Chris Rea. We had the music in advance. I could direct the animators very closely to the music.

Madhouse (1990) opening title sequence designed by Sally Cruikshank

I think the goofy character with the buns on her hair – I really liked the way she’s animated. I really like the way we did all the looks. Except for the sound effects, again! Haha. Playhouse was producing it and they just had different ideas about sound and how to design that.

Did you get any direction from the filmmakers for Madhouse?

Well, I was directing the sequence, but, you know, I designed it and then I would pass on the layouts and Gerry would talk to the animators about what I wanted. They really did a good job on that one. Because it was about a whole bunch of people coming to stay in one house, it has a lot of little shots in the titles where there are many characters, and everybody’s doing something different. And they’re doing it to the music, too!

And then of course there’s that cat…

That cat, yeah! The titles look better on film and cel than they do on YouTube, of course. That’s always the way.

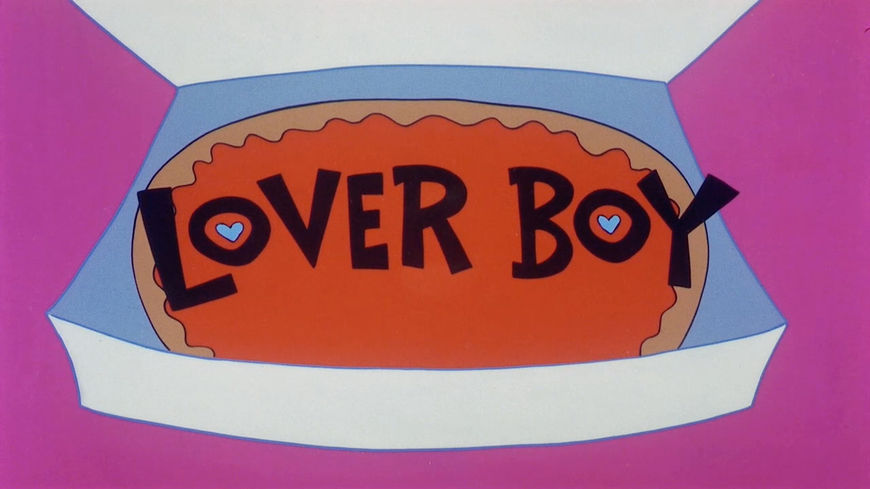

Let’s talk a little bit about Loverboy.

On that one, I can’t remember it very well! The couple – Ropelewski and Dixon – they had been the ones who had brought me in on Madhouse as well. But I was pregnant, close to having my daughter at that time, so there’s a memory gap there! I may have just done the basic drawings and turned them over.

When I looked at the titles again recently I thought, it’s not so bad! I remember thinking the movie was awful, even though [Joan Micklin Silver] was a very respected director.

Loverboy (1989) main titles designed by Sally Cruikshank

Whose idea was it to jumble up the letters so that the credits read as something else first?

Well, I would think it was mine, because I was thinking of pizza toppings. Probably was. That’s the kind of thing I would do… how my mind works.

Still from Loverboy's opening title sequence by Sally Cruikshank featuring a pizza loaded with anchovies.

Would you ever order extra anchovies, like in the movie?

Yeah! I love anchovies.

Did you switch out of doing title design after this consciously? Or did it just sort of happen?

No, I just never had an agent! All the work that came to me just came to me – and then it stopped. It didn’t seem like there were many animated titles for a brief period in the ’90s. As you know, animated titles go in and out of fashion so much. Styles go in and out of fashion. I did notice that when I looked at the Woolery's Playhouse archive, there were so many animated commercials for beer. And it was all pitched to men! Black and white commercials of men going to the fridge to get beer. It seemed odd.

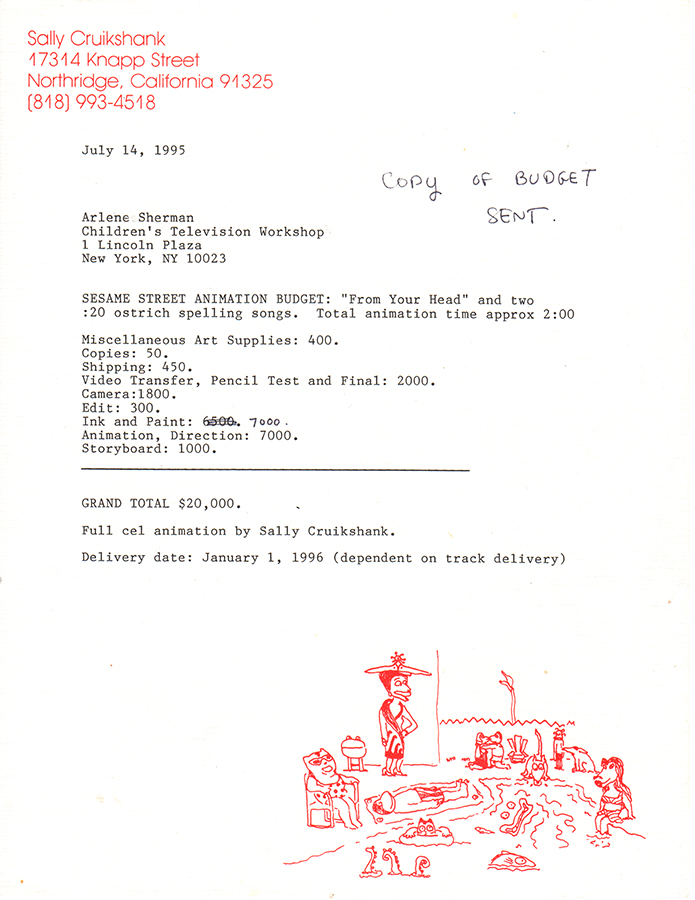

I would have liked to continue to do titles, but I didn’t have an agent. Then Sesame Street contacted me out of the blue! This wonderful woman Arlene Sherman called me up and it was amazing. After all that time – I’d always hoped I could get Sesame Street work – and finally it just happened. They hired me to do three songs right away around 1989 or 1990 and she was just a wonderful person to work for.

The original budget for the animated sequence "From Your Head" featured on Sesame Street, on Sally Cruikshank's letterhead, 1995.

It was so easy. She would send a song, I’d send back storyboards, she’d almost always approve them unless there was something that violated the Children’s Television Workshop bible laws. Then I’d go ahead and animate them, send her pencil tests and she’d approve that, I’d do the ink and paint, and it was over!

And the tracks were always so lively and witty.

What was Arlene’s role?

She was a producer, and she was there for maybe 15 years. She died four or five years ago and I could never find out much information about that. She was so great to animators. I wasn’t the only independent animator that she gave these opportunities to, but I seem to have gotten the most songs. I remember being on a panel with her in Pasadena, and she was just swamped with people saying, “Would you look at my portfolio? Would you look at my reel?” because it was one of the main chances people had as independent animators to break in. She had to really be stern about it because it was so overwhelming.

Original storyboards for "From Your Head" animated sequence by Sally Cruikshank for Sesame Street

Working on Sesame Street was really fun. I really liked the work I did for them and they rarely seemed to be teaching you anything! And folks on YouTube, they post the loveliest messages about how they see the video and, you know, “I’m back eating a peanut butter sandwich. I loved this.” But my own daughter couldn’t have cared less! She was exactly the right age for it, and she would leave the room when Sesame Street came on.

It just wasn’t her thing?

She didn’t care for television! That was different.

What were some of your favourite projects that you completed for Sesame Street?

Well, my favourite is “From Your Head.” It was so challenging to come up with images because the lyrics were so abstract – thoughts come from your head, dreams come from your head, songs come from your head. The lyrics were very hard to get a hold of.

Some others were, too, like “Beginning, Middle, and End.” That was a tough one to come up with images for. I like “Your Feet’s Too Big,” I like “I’m Curious” … there are quite a few of ‘em! But “From Your Head” was my favourite.

They were all satirizing music. They had very clever lyrics and clever music, which sometimes I was not aware was taking off on current music of the time. Like, “Beginning, Middle, and End” people kept saying it was like some other song… but I wasn’t very into contemporary music. “Above It All” was one that people just love, and I just thought it was awful. People always say, “Oh, I love it so much, I remember this one” though.

They were easy to produce because I did all the animation, so it was all me. I didn’t have to be giving instructions to someone else and explain what I was trying to do. I didn’t do the ink and paint, and sent it off to Canada to be Xeroxed.

You sent it off to Canada?

Oh right, you’re in Canada, yes! The Xerox folks were in Vancouver. By that time, the Xerox technology was appealing to me more. I would just trace the pencil drawings on paper, first with a Nietzsche Stylus pen, in the early days. Then I started experimenting and found I could use a nice Tombow marker. I don’t know if they still make those or not, but it had a very flexible felt point and I could get a thick and thin line that didn’t look like the usual Xerox line. I was very happy with that. So I would send them over, and they would Xerox it, and get it all registered correctly, and send them back to me, and then I had them photographed in Los Angeles.

From Your Head animated by Sally Cruikshank for Sesame Street

How long did you work with Sesame Street?

I think it was fourteen years or something like that. My whole life, it’s been a sort of – they call me, or nothing happens.

A very serendipitous sort of career.

Yeah. I did have an unusual job briefly, working at a think tank in Palo Alto, called Interval Research. It was a Paul Allen think tank and they were designing a game that was way ahead of its time, in which a child would dance in front of a computer and see himself in animation doing the dance on the computer screen. I was doing some animation for it, but I’d never even used a computer before! They ran into problems because at that time nothing was wireless. So if people even had a computer, it was probably in a little office with a whole lot of wires all over the place, and it was probably their parents’ computer. And then the camera would’ve been on a tripod and so… the whole thing just kind of fell apart. This was the mid-late ’90s.

So it was just before that bubble?

Yeah. And that got me started on computers! I thought that it was so wonderful that you could self-publish on the Internet. Aw man, I thought, this is the greatest thing! So I learned how to do animated GIFs and I made a little comic strip with my character Anita and another character, Whinsey. I tried to publish one every week.

Talking horse Whinsey works in an appliance store in an alternate universe in Whinsey On The Phone, one of Sally Cruikshank's cartoons made with Flash.

You know, now I see this was the beginning of the whole free content thing which has really taken artists down, but at the time it just seemed amazing. I learned code to try to make them interactive.

First I was doing it with GIFs and Javascript, and then I was doing it with Flash and ActionScript. I developed a chatbot that you could type anything into and she would have a sort of wacky but vaguely reasonable reply to what you said. I used all sorts of PHP scripts. I mean, I was deep into code!

I think we all were, at that point!

Yeah, haha. As I got the chatbot smarter and smarter, I would have these external scripts that would go to places like Google. It would grab one word from the user, and then throw that out to Google, and get a reply, almost a definition, and break it up to sound almost conversational and a little wacky as she returned it. But every time the source changed the layout of their pages the scripts would fail, because it was so dependent on the PHP reading the exact code.

The other thing was, I was trying to make her smart. I was trying to make her so smart that you could say, “Who is Sylvia Plath?” and she would come up with a funny reply. But all people wanted to do was say dirty things! And she’d say, “Oh no, jeez, gross. Get a life!” She’d say, “Ask me something smart!” you know?

Screenshot of Whinsey the chatbot developed by Sally Cruikshank

So she was like a sassy, proto-Siri?

Yeah! She was. She was a talking horse, though. She was sitting in a barn talking to you. She had this little TV on her desk. So it would take the word which seemed the most significant in anything that you said to her, which is usually the one with the most letters, and it’d send that to Google Image and then it’d pull back the first image there, and it would go on her TV, and you’d think, “Wow, how’d that happen?” It was obviously much more surprising in those days, you know, not like now where you have Siri and so on. It seemed really like, “Whoa!”

But, you know, I got very discouraged because of how rapidly, in computer-land, formats become obsolete. I did all these games that worked in the Internet Explorer browser version 5 or 6, but they don’t work anymore. And I did an extended series where my characters went on the Titanic, using a lot of script. This was before Flash was entirely scriptable. I mean, I spent a lot of time on the artwork and story, there was even music and this wasn’t that long ago, but it’s all obsolete now! It’s just amazing how quickly digital formats can just no longer work. There was all this Internet work but nothing was really on a screen that a large group of people could see.

I didn’t really do much design-wise until Smiley Face.

Smiley Face (2007) main titles designed by Sally Cruikshank

How did Smiley Face come to you, after all those years away from feature films?

I think it was through someone named Marcus Hu who’d been a fan of mine for a long time, though I didn’t know it until later.

With Smiley Face, I did it in Flash, and it was very difficult to get it from Flash to film. Film was still the medium then. Had it been like three years later, it would have been a breeze! By then, movies were all digital. But for the Smiley Face process, it was not that easy. I had to output a stream of TIFFs and I wasn’t there when they did the colour correction, so I think a lot of the gradation turned out pretty crappy. You could get these wonderful gradations in Flash, but I don’t think they turned out right in the film.

Then, right around the time the film was to be released, there was some awful falling apart with the production company and the distribution company, I never quite understood what happened, but the film was sold and dumped and it didn’t get properly cared for as it went out. I’m not even sure it got a US release!

Gregg insisted that I caricature all of the major actors. I was like, “Aw man, I gotta do people? I can’t do cats and ducks?”

For me, that was a challenge. I wanted to do more involving the smiley face and circles and things changing into other things – more of a style I’m comfortable with – but he wanted the caricatures.

He also wanted it to be a really fast tempo, with short cuts on each person’s credit. I was looking at it today and I thought, “Wow, that goes by so fast!”

Were you able to work with the music when you were animating?

I don’t think I was working with the music. It seems to be working pretty well with the beat, though. Animation can be deceiving that way – your eye wants to sync up music to animation. I can’t remember if I came in and did my work ahead of it or if I just jiggled with it enough that it eventually synced together.

Looking back at this, seeing as you’ve just rewatched it, what do you think the title sequence gives to the film?

Well, it doesn’t even come in at the beginning! It comes in quite a ways into the film. It gives you that dopey, doped-out feeling pretty well. It shows that she’s going into this weird world.

Do you think you have any personal favourite title sequences?

The Pink Panther ones are so great! And I do think Saul Bass’s titles are really great but there’s nothing there to surprise you or anything.

I think title sequences are underappreciated. People remember them as being good, but they don’t really have a proper knowledge of them… they haven’t been collected very carefully, right? That’s probably what you’re doing!

Yes, exactly.

Haha. It really can have an effect in an audience situation, rather than when you’re sitting at home with a little screen. Certainly they can jolly up a big audience, warm them up to what they’re gonna see, whether it’s making them laugh or feeling kinda good.

Right, and there’s actually been kind of a resurgence in animated sequences, especially for end credits. Did you notice that?

No, I haven’t noticed that! That’s nice, that’s good.

Maybe you can dive back into it.

Haha. Yeah! I don’t know, I might be done. The last animation I did was for the song Nite Owl, just ‘cause I like the song. I did it with Flash. But for all the time I spent on Flash, I never felt like I could completely get what I wanted to get out of it. The look I wanted. I would always settle for much less, but I would never do that with regular animation. Often when you’re working with code, you just want to see if the code works. But then you don’t go back and fix it so that it looks great.

So, are there any cartoons or animated films that you would recommend? Ones that had an effect on you?

A still from Makin’ ’Em Move aka In A Cartoon Studio (1931) by Studio Van Beuren.

Oh sure! I wasn’t that big a Disney fan, ever. And I’m not a big fan of animators like Tex Avery, like most people are. I love the Felix the Cat shorts from the ’20s, the Max Fleischer cartoons, Betty Boop and Bimbo from the early ’30s, the ones from Studio Van Beuren. They had one called Makin’ ’Em Move, and then it was called In A Cartoon Studio, and it was a really funny vision of how cartoons were made. I liked some Warner Bros. Oh, Winsor McCay, you know!

Also there was Story From North America, about this boy that sees a spider under his bed and he sings in this really rough voice, “Daddy daddy” and he comes in and he looks like God. It’s just odd, and I like that.

Did you ever check out some of the NFB’s films?

Oh yeah, I liked this one – I think it was put out by the NFB – called The Street, by Caroline something?

Oh, Caroline Leaf! Yeah, I love that one. It’s so nice, and smudgy. What kind of advice would you give to someone thinking of a career in animation? There’s a whole new generation of animators these days.

Haha, I don’t know. You might consider science, instead! I’d say to learn code, actually. The way I learned code was just seeing other people’s code and switching out variables and seeing how things work. You can teach yourself code, and that’s what I did.

And keep drawing! It’s a very pleasurable thing and it’s very exciting to see your drawings move. A basic knowledge of code would help you transfer to digital formats.

Thank you, Sally.