It is a feat of power and vision, flexibility and choreography; awe-inducing movement that is beyond description. A moment to revisit. What would it be like to hold the camera and do this, to push the story, to really exert a vision, to strain the frame in service to it?

The liquid-like immersion into story deepens with these shining selections of streaming sight lines.

We have a few categories we’ll break out over the coming months. In keeping with the long “single take” theme, we are going to take our time with this feature post. When we are near the end we will put a call out for suggestions. Until then, tuck away your title lists and revisit your favorite films.

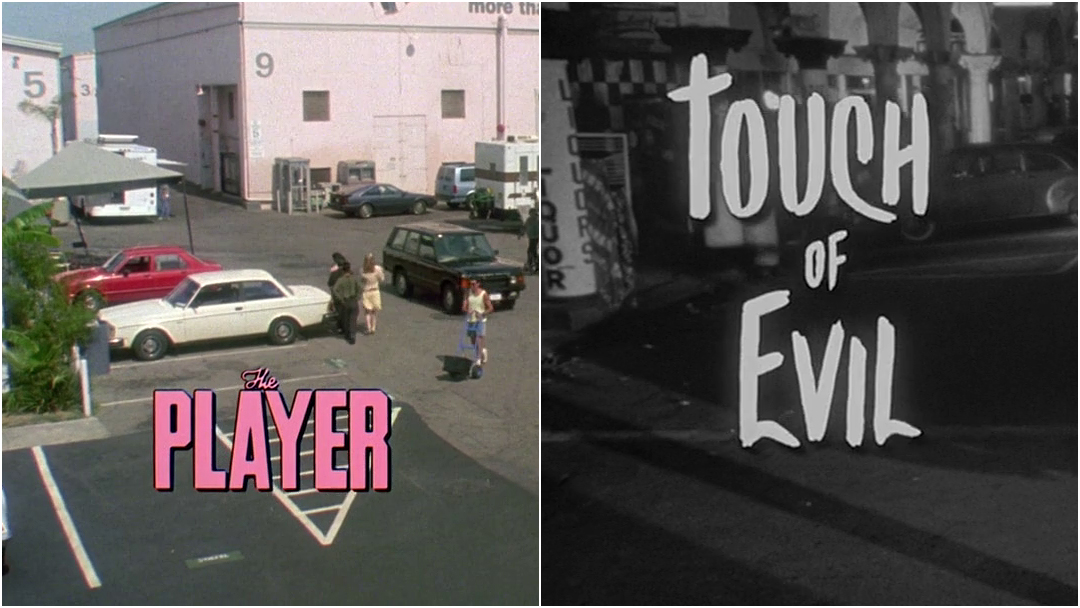

The Player

A self-referential introduction to the world of make believe, the opening single take sequence to Robert Altman’s The Player is a formula-bending ode to a classic. Altman’s wonderful analog parlor patter follows the scenery as the storyline unfolds between storylines. Clever quickly turns classic as the film is established as something more visual flourish than acerbic satire. The sequence segues nicely to the next title in this ongoing “Single Take Titles” feature post.

From the 1997 New Line Platinum Series DVD, Robert Altman on The Player:

I had to set up the movie studio and wanted to set up the characters that we were going to be dealing with and I wanted to get the audience’s attention, to tell them that they had to pay attention. And I actually built a scale model of the set with a crane to see where I could go. Then we choreographed all the positions. We introduced this [film] in one reel, which was nine minutes.

All of the various things that happen were all planned pretty well, but none of the dialog was. It was all improvised…We did about 15 takes, with 11 microphones. We rehearsed it for a day, we lit it and came back the next day, which was a Sunday, and we shot it in half a day. It turned out to be a very efficient way to get ten minutes of film. And you save your editor’s fee. It’s a very conceited thing, this shot with no cuts, it draws attention; it’s of the mode of people who make pictures. It is showing off. It sets the picture up…it’s like music [in that] it tells you what kind of deal you’re in. It’s a satire on the way people behave in these movie studios.

There was such a fuss about it. People were afraid I was going to do this or that. The more afraid they got, the more ideas they gave me. Looking back on this picture, it is a pretty tame satire. This is no big indictment. Things are much, much worse than this picture seems to say. The truth of the matter is I cannot make the kind of movies [Hollywood] wants to make. The kind of movies that I like to make, and can make, and make are not the kind of films they know how to distribute. So we basically aren’t in the same business. There’s no point in calling me to make a pair of gloves for you when I make shoes.

Touch of Evil

Ticking tension takes a ride.

A classic Mexican mop up with bang bang follow-through, the opening sequence to Orson Welles' Touch of Evil is the granddaddy of the long take title. Every element is note perfect from the off screen ambling death psychology of a 1956 Chrysler New Yorker to the protagonists' own circumnavigation at the mention of "the Grandi business."

Note that the theatrical version has titles and Henry Mancini's theme music while the restored version, closer to Welles' vision, is without titles and features "a succession of different and contrasting Latin American musical numbers – the effect, that is, of our passing one cabaret orchestra after another." (quote from Orson Welles' legendary memo to Universal)

Theatrical Version feature audio commentary excerpt with Writer/Filmmaker F.X. Feeney from the Universal Studios' 50th Anniversary Edition DVD:

Welcome to the 1958 release cut of Touch of Evil. This little egg timer is set for precisely three and a half minutes. Tick, tick, tick we're embarking on a combination thrill-ride morality tale bursting with the energy of its co-star, writer and director Orson Welles. I love the fast-running shadow along the wall. Of the three versions that exist of Touch of Evil this is the fastest-paced, the most energetic. It's missing about six minutes of material Welles would have preferred to include. In harmony with our ticking timer and our deadly bomb this astonishingly complex master shot is going to unfold across precisely three and a half minutes. Shadows are like a Greek chorus commenting on the action in Welles-O-Vision, so is this airborne camera moving like a winged serpent over these rooftops and streets.

We are in the mythical U.S./Mexico border town of Los Robles. Connoisseurs of L.A. architecture will recognize the looped arches and fanciful galleries of Venice, California [which was] built in the 1920s by Abbot Kinney, a developer with a mad crush on Venice, Italy. These magical facades were ideal for Welles' purposes as storyteller. They anchor us in a place apart from either the U.S. or Mexico. We can think of it as a geographic Twilight Zone.

Here are the two great romantic leads, the two greats of their time, Charlton Heston and Janet Leigh as Mike Vargas and Susie.

Henry Mancini's music here is sensational. He organized a latin-style band using talent from outside Universal Studio. It's a perfect counterpoint to the sensuous muscularity of the camerawork and the very precise criss-crossing of all the people; an enormous operation. Welles originally intended that the music blasting from the cantinas would create a surf of sound and atmosphere (for that see the 1998 Restoration cut where those intentions are scrupulously honored). But I have to say, as a life-long fan of the film, I find Mancini's magnificent overture indispensable to the power of this opening, I even prefer it, with all due respect to Welles.

Small wonder there is an explosion when these two kiss. The blast plunges us into another world altogether. We are free of the elaborate crane and we are running with the characters [the camera is] handheld.

Restored Version feature audio commentary excerpt with Charlton Heston, Janet Leigh and Restoration Producer Rick Schmidlin from the Universal Studios’ 50th Anniversary Edition DVD:

Charlton Heston: The beginning of the project...I read the script and thought that it was okay...it was a police story [so I mentioned] that they had been doing police stories for fifty years, [so] who going to direct? [The studio] told me that they got Orson Welles to play the heavy and I said, "Why don't you have him direct? He's a pretty good director." They seemed surprised at that but in the end they gave in and here we have the beginning of a remarkable film.

Janet Leigh: I remember we were [shooting] all night to make this one extraordinary shot. It was tedious and long but we knew it was a historical shot.

CH: Of course the shot was enormously difficult to do with a Chapman Boom...and it was further complicated as we get to the border crossing [in the scene]...the music is of course a marvelous contribution to the whole.

JL: [the music] gives the feeling of a border town.

CH: The border guard had a terrible time remembering his lines. You can see that dawn is breaking. This was the last time we could possibly do this shot and Orson said "We will do one more take." And then he told the guard, "This time, don't you say anything. Just move your lips and we'll post-dub it, but for God's sake don't say 'I'm sorry Mr. Welles.'"

Rick Schmidlin: [As the onscreen Charlton Heston & Janet Leigh kiss prior to the explosion] Okay, I want you to watch something here. Watch the shadow against the wall. Who does that look like?

CH: Orson

JL: It looks like [Orson's] Quinlan.

Preview Version feature audio commentary with Orson Welles Historians Jonathan Rosenbaum (Author, “Discovering Orson Welles“) and James Naremore (Author, “The Magic World of Orson Welles“) from the Universal Studios’ 50th Anniversary Edition DVD:

James Naremore: This is the second version of Touch of Evil.

Jonathan Rosenbaum: [This] was found in the mid 70′s and it 15 minutes longer, but we should emphasize right now that there is no such thing as a director's cut, nor could there be. This is another version that was found that has more material by Welles but also more material not by Welles.

JN: One of the things we are seeing that he didn't originally plan is the credits are playing over this sequence that [Welles] wanted without the credits...the photographer for this film is Russell Metty, a contract photographer at Universal and he was well known for his use of crane shots.

JR: This is the most famous shot of the film, but Welles himself was much prouder of a couple of other shots he did later in the film because this is the kind of thing that calls attention to itself whereas he thought that the most effective virtuoso work was the kind that wasn't noticed by the audience.

JN: This shot is not simply a flamboyant tracking shot, it also has to do with the theme of the film. The film is very much about the ambiguous border between the U.S. and Mexico...the two leading characters are representatives of either side of the boarder and there is a kind of racial/ethnic theme running through the film. It's almost as though the kiss between the Mexican character and the woman from Philadelphia sets off racial tensions. The timing of the kiss is important in relation to the explosion.

JR: This has got to be Orson Welles most politically incorrect movie, which is one of its strengths.

JN: Yes, and it is very much a political movie...with the explosion, the film shatters into montage. We might want to keep in mind that this film was shot not too long after the Supreme Court desegregation decision of 1954, the integration of Little Rock high school had taken place, the Civil Rights Movement had begun, and Welles had a long history of being involved with activities of that sort. And, in this case, he had completely transformed the novel that this film is based on (Badge of Evil by Whit Masterson) and made it into, I think, an indirect commentary on racial tensions in the United States.

Touch of Evil (1958) main titles (restored version), directed by Orson Welles