The Steadicam is a combination of several large pieces of equipment, worn on the operator’s body that support the camera. The design of the equipment allows for the operator to walk and move about, without translating his or her footsteps or other vibrations into the lens, and subsequently the shot. —Steadishots.org

A jitter-free alternative to expensive and laborious tracking platforms, the Steadicam “revolutionizes the ways films are shot” (Stanley Kubrick). The apparatus’ XYZ axis of motion is an easily rotated flotation device for the director’s vision. It is reliant upon the camera operator’s athletic grace and sense of composition. It is a visual language.

Our thanks to Afton Grant, a Steadicam owner and operator from New York, who’s excellent Steadishots website was an invaluable resource in the creation of Single Take Titles, Part 3, and who’s commentary highlights each film here.

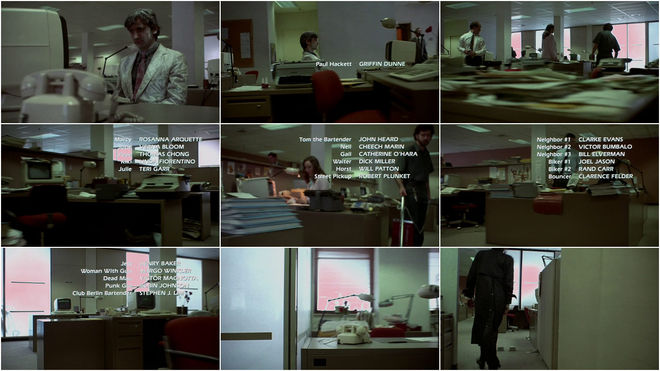

After Hours

A synthy clarion bell beckons a plaster-dusted (but alive) Griffin Dunne’s “Paul Hackett” in Martin Scorsese’s After Hours. Note Hackett’s elevator door-reveal of an expression that Robert Downey Jr. has come to own over the years. With Mozart elevating the sequence the camera’s movement casts a damning eye upon the worker hive. The film is a Kafkaesque (thank you kindly, Mr. Roger Ebert) salve; Paramount had just canceled Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ.

Afton Grant, from the Steadicam resource site Steadishots:

This is a very fun little shot, though not simple in any way. Done in low mode, at a relatively quick pace, this shot displays the great importance of good dynamic balance. With the fast paced pans and turns around the set, if the sled had not been balanced properly, it would have rolled very dramatically with each turn.

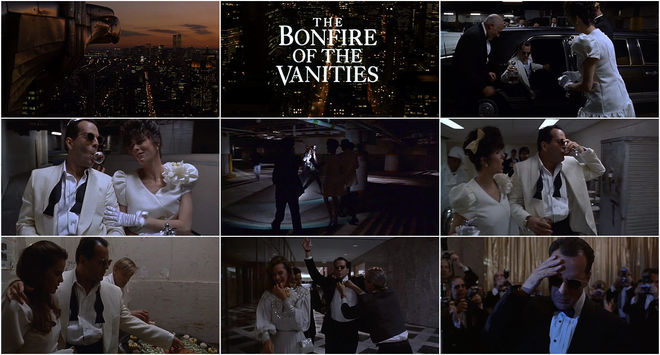

The Bonfire of the Vanities

After a time lapse shot for the ages an air of inebriated whimsy ushers us along with the Bruce Willis character.

Afton Grant, from the Steadicam resource site Steadishots:

This would be one of the more famous opening sequences in the world of Steadicam. An almost 5 minute take, executed to near perfection. McConkey's skill can really be seen in the final few seconds of the shot where the motion slows way down and ends in a lock-off with perfect headroom, horizon, and no wiggle.

Commentary with Steadicam operator Larry McConkey:

I fell on the very first take, due to the introduction of an ice sculpture that extras were wheeling in front of the camera for the first time on the take. Up until then they had rehearsed with an empty cart to save the ice from melting. The extra weight slowed them up considerably. I was following the actors into the underground garage and I had choreographed the ice sculpture to wipe through frame between the actors and me before after which I planned to race in front of the group in time to back through a narrow doorway.

Unfortunately there was an army of people trailing me who had to then race around and precede me through that doorway (Brian, Vilmos, AD's, sound, my assistant, etc.) and there really wasn't enough time. Someone tripped my AC, Larry Huston, who graciously offered his body for me to fall on top of. I was completely unharmed, as was the rig, but Larry H. had a nasty gash in his head. He refused a ride to the hospital so we could continue to work, and the nurse reopened his wound after every take to keep it from healing improperly until he could get stitches. What a trooper!!

Brian, who is a master tactician and strategist just hadn't considered this possibility: he stood over me, and after seeing I was OK said "I didn't think you could fall!" He had anticipated every potential disaster but this one. We did another 11 takes until dawn when Vilmos informed me that this last take "must be the one!!! The light at the beginning and end were perfect, and that WAS the one.

Each take was a full 500′ and the shot was over when the end of the film flapped through the gate.

I wanted a device to let Bruce pass by me a little too close to the camera for focus in the elevator, and he came up with the idea of scooping up some salmon mousse, and twirling a little drunkenly past me. This also delayed the action enough for the rest of the crew (same group as before except for Larry H. and the boom woman with a wireless boom mike who rode with me) to exit the elevator next to us. They were timing their elevator to synchronize with ours on the way up to maintain a good RF link to the mixer. If the elevators rose side by side it worked fine, otherwise complete dropout.

After exiting, I wanted to get back in front of Bruce so he came up with the Mousse Toss onto the wall thereby backing away from the camera enough to allow me to make a clean exit. There were many other devices like this throughout that I came up with to make the shot flow... I figure the more work everyone else does, and the less work I have to do, the better it will look...

Snake Eyes

Here comes the pain.

Feeding off Nic Cage’s dickish-but-funny vapors the opening sequence to Brian De Palma’s Snake Eyes impresses as bits of narrative register and bullets fly. The sequence plays continuous but reportedly has eight cuts. Where are they?

Afton Grant, from the Steadicam resource site Steadishots:

The full opening sequence continues for almost 13 minutes but the first 7 minutes contain the best examples of the Steadicam work by McConkey. Within the full 13 minutes, there are 8 well hidden cuts, mostly in either whip pans or something crossing full frame.

This shot, and the sequence as a whole, are excellent examples of a director’s vision, and understanding of the tool. Add to that vision, a great amount of trust and collaborative respect for an operator, and you get a shot that people talk about for years to come.

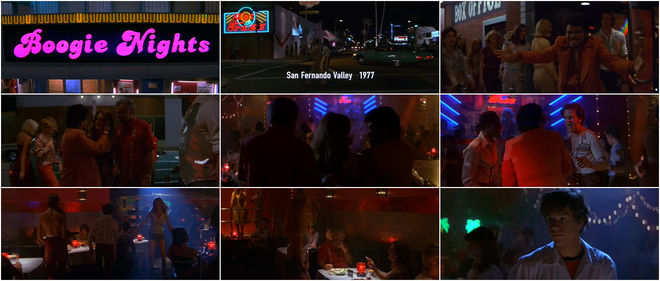

Boogie Nights

After what can be described as an Balkan sounding prelude over black pops practical bubble gum type. “Doesn’t take much to make me happy.” The camera swoops like Burt Reynolds eyebrows and rolls like Heather Graham bringing us into the club making introductions.

From the Steadicam resource site Steadishots:

An amazing opening sequence. Starting on a crane, moving through a couple dutch rolls and tilts down to the ground, entering the club, and tracking the action for nearly 3 minutes.

Outbreak

As we skirt a declared national emergency in H1N1 let us consider Wolfgang Petersen’s employment of the long take title sequence in Outbreak; touring the military’s Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases, specifically the various “biosaftey levels” of the Virology Section (from Salmonella to Hanta to the reassuringly-described “unknown”) in a single take grounds us in discomfort.

From the Steadicam resource site Steadishots:

This is an excellent opening POV sequence. Such a long opener requires an incredible amount of coordination. Take note of the many cues and actions that move the camera in and out of the rooms and hallways.

The continuous appeal of Joss Whedon’s characters on the raggedy edge is on parade to begin the title sequence ofSerenity, his film based on his Firefly television franchise.

Afton Grant, from the Steadicam resource site Steadishots:

An excellent single shot in a movie that, unfortunately did not get a lot of attention. This opening sequence is fantastic. The set is a large part of a spacecraft and the camera goes all through it – upstairs, down corridors, through doorways and more.

If you watch closely, slight zooms are used to close and retreat larger distances without forcing the camera operator to break into a run, or crowd the actors, or backpedal quickly.

Durval Discos

When Art of the Title watches a fluid Steadicam composition what takes place is a kind of sustenance.

Filmed at Rua Teodoro Sampaio, famous in São Paulo (Brazil) for its concentration of shops selling musical instruments, the opening sequence to Anna Muylaert’s film Durval Discos is organic in its ease as DP Jacob Solitrenick treats us to the relaxed pathology of the street.

At once you figure the arrangement and mute any notion of it, allowing the credits to simply come when they come.