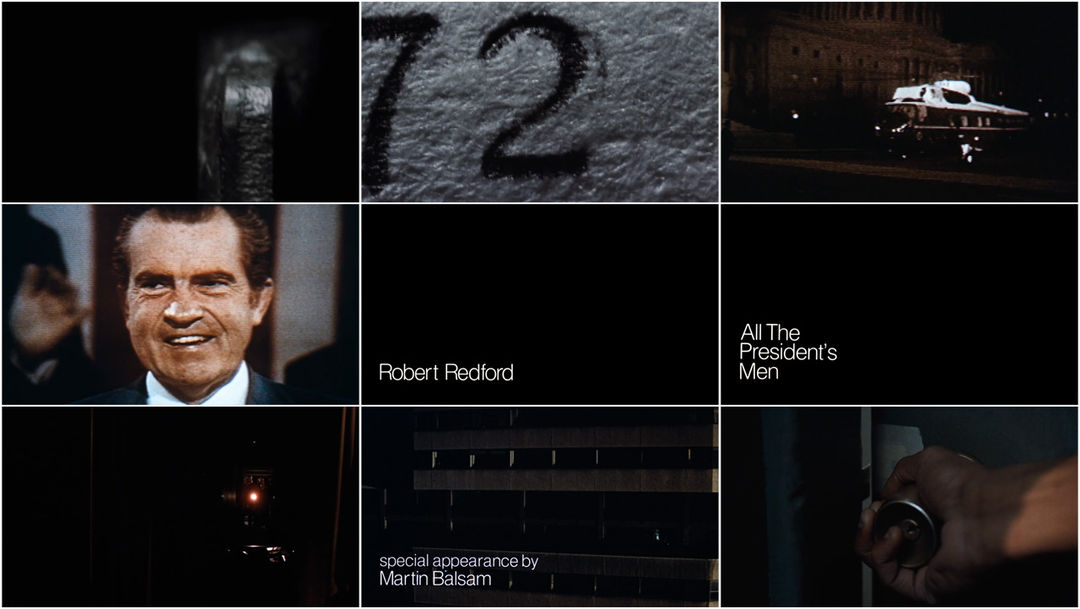

Though it centers on one of the greatest political scandals in living memory, director Alan J. Pakula’s 1976 film All The President’s Men starts the same way most stories do — with a writer staring at an empty page.

After a very pregnant pause, a typebar hits the paper with all the force of a cannon shot, inking the letter J and snapping viewers to attention. Three letters, two spaces, five numbers, and two pieces of punctuation are then delivered in quick succession, like a boxer working a heavy bag.

June 1, 1972.

Blank paper can only become something more through hard work, tenacity, an unhealthy supply of caffeine, and a whole lot of luck - and even then there’s no guarantee that anyone’s going to read what’s printed on it. But with a lede as compelling as the opening title sequence of All The President’s Men, the viewer immediately knows that this is a story worth investigating.

Barely four years removed from the notorious Watergate scandal, a piece of actual news footage helps to anchor this political potboiler firmly inside the Beltway. The viewer knows this story is far bigger than Washington, D.C. though. A smiling President Richard Nixon has just returned from his historic trip to China and is about to address a joint session of Congress, oblivious to the fact that just two weeks later events would transpire that would eventually lead to his resigning in disgrace.

Fade to black — A shadow-filled hallway in the Watergate Hotel, hushed voices, and the sound of a lock being picked. Slight, white Helvetica typography breaks the darkness just before the burglars make their presence known, the credits and title card quietly phasing in and out as if trying to avoid detection.

Uncredited authors Gemma Solana and Antonio Boneu on title designer Dan Perri’s typography:

Uncredited: Graphic Design & Opening Titles in Movies

by Gemma Solana and Antonio Boneu.

The choice of a Helvetica at a time when typographic excesses were still the rage, the clarity and intentional dryness of the composition, and the absence of music make for a title sequence very advanced for its time.

Until this point in the sequence, the instructions laid out by screenwriter William Goldman have been largely ignored by Pakula and Perri. Goldman’s script provides little in the way of direction for the opening, stressing only that the movie should start with “as few credits as possible.” Perri’s minimalist type design adheres to that request in its own way, leaving the viewer with only fleeting impressions of names and titles before disappearing into the night.

Goldman’s screenplay does however outline the film’s only real set piece — the Watergate break-in — focusing on the many “if-onlys” that could have changed the course of events. As the sequence comes to a close, the audience gets the first of those “if-only” moments: Watergate security guard Frank Wills (playing himself) discovers tape covering a door latch. Two years later, Nixon would become the first US president to resign.

Main title designer DAN PERRI revisits his work on the opening title sequence of All The President’s Men and discusses its creation.

What was the first meeting like about the project?

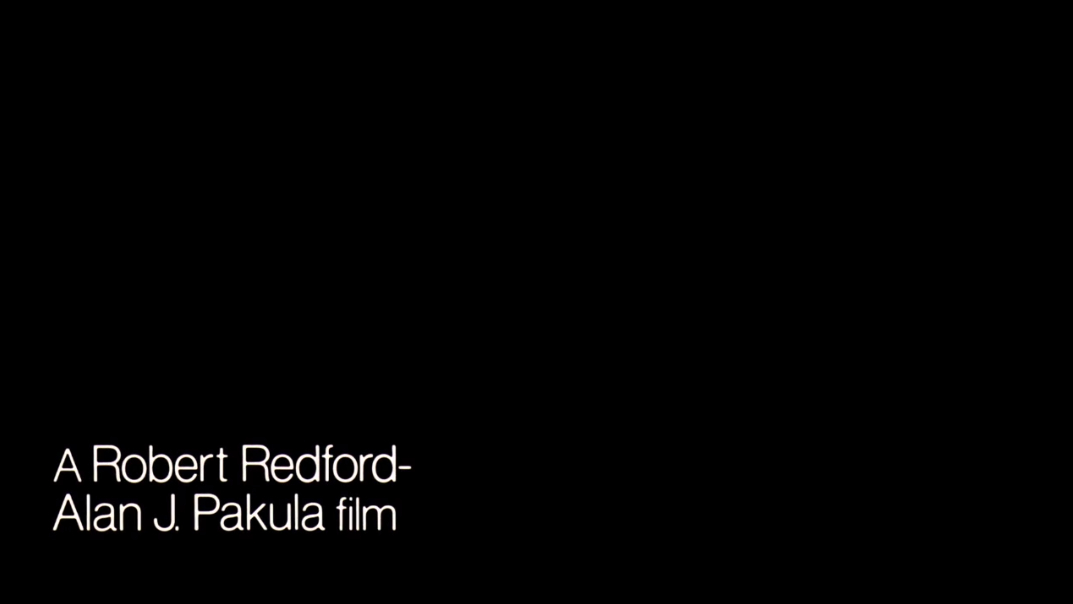

DP: When director Alan Pakula asked me to design the titles for All The President’s Men, he told me that producer and star Robert Redford had to approve of me first. So, I was invited to meet him at his Wildwood Enterprises office on the Warner Bros. studio lot. Out in front of his bungalow was a beautiful vintage Porsche 911 coupe. It was one of many that he owned. He drove a different one every day.

Director Alan J. Pakula and actor Robert Redford on the set of All The President's Men

I entered an ordinary reception room and then was taken into Bob’s inner office, which was totally converted into a Western-era line shack. The walls and ceiling were covered in distressed wood, the wooden floor had a bearskin rug, and there were Western objects and artifacts that filled the room.

He was immediately cordial and friendly and as soon as we learned that we went to competing high schools in the San Fernando Valley – though he was several years ahead of me – I was in. We laughed and swapped stories and then I went off to work.

What were your initial ideas for the titles?

DP: After viewing a cut of the film, I thought the titles should be as secretive as the story and the characters. I suggested the thinnest weight of Helvetica in caps and lowercase to represent the anonymous nature of the characters. They had to be very quiet as they entered, small and elegant and almost unnoticed.

There was an opening exposition sequence establishing the underground garage and the 28 opening titles were to be over these scenes. I made them very dark gray so they almost completely blended into the backgrounds. I tested various sizes in trying to make them as small as possible. Then, I placed them as close to the lower edge of the screen as safe title area allowed.

Sequence still: Robert Redford and Alan J. Pakula's executive producer credit

I experimented with fade lengths and finally arrived at a length for the fade in that was half of the on-screen reading time and then the other half was for the fade out. They came in so smoothly and quietly, like smoke, then they died away gracefully. It was beautiful.

After I’d finished the main titles and Alan previewed the film, he decided to change the lengths of many backgrounds and I had to re-do the sequence many times. Alan was known for his indecisiveness. There was a joke in the editing room that due to his unending changes, that the film was finally in single-frame splices held together completely with editing tape. It wasn’t far from the truth!

The preamble sequence of Nixon arriving at the White House abruptly began with an ECU [extreme close up] of typewriter keys slamming into a piece of paper. It was very powerful and demanded your immediate attention. It spelled out the date that Nixon arrived in Washington.

I had wanted to further punctuate the impact of that moment by holding off the shot – just holding a black screen almost interminably until the audience began to think there was something wrong and then – BAM!

Sequence still: the letter "J" as hammered out by a typewriter

The first sharp report would hit and they’d be thrown back in their seats. We tried it and it worked nicely, but eventually the Warner Bros. brass overruled it for a shorter length.

Do you have any other interesting stories about this sequence?

DP: After several previews, Alan felt that the ending wasn't working and decided that we needed to sum up the story of these two reporters writing all of these revealing stories that made the front page of the newspaper. We decided that seeing every important front page of every date during those weeks of historical events would be the most direct and organic way to sum up the story.

So, I was dispatched to fly to Washington DC to The Library of Congress to photograph every front page, then rush back to LA and create a montage to close the film.

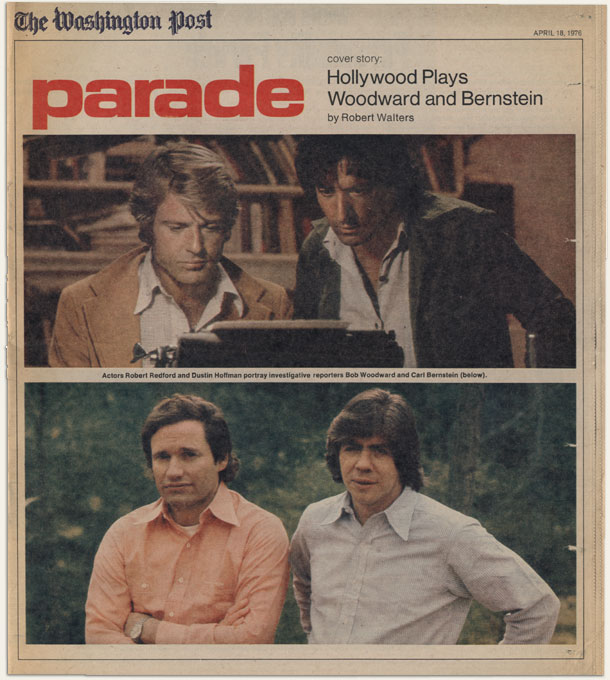

Redford and Hoffman as Woodward and Bernstein (affectionally called "Woodstein") on the cover of the Washington Post Parade, April 18, 1976

On a Friday night in January, I took the red-eye on the coldest day of the winter and took up residence at the Watergate Hotel. I hired a local photographer and on the following Sunday morning The Library of Congress was opened up just for me and I met the curator there to gather the various editions with their special front pages.

She pulled out every required date and right there, at the entrance to the metal vault, we kneeled down, laid down some paper, and photographed the front pages – right there on the cement floor of The Library of Congress.

The photographer gave me the rolls of negatives and I raced to Dulles, hopped on a plane, and was back in LA by nightfall. The next day I had the negatives developed and special prints were made while I designed the sequence. The following day I filmed it on the animation stand.

It was done, delivered, and cut into the film by the end of the week. Alan was very happy with the outcome. He didn’t even change it and the film was released in April 1976.

The end credit sequence you describe isn't actually in the final film, though. Did they not use it?

DP: Interesting you should mention that because I only remember all the travel, cold weather, and hard work to create that sequence! I never went to the cast and crew screening, nor did I ever see it after the release to have noticed that it wasn't used. So it's news to me. In any event, I did the work, delivered it, and Pakula – at the time – was happy. Who knows!