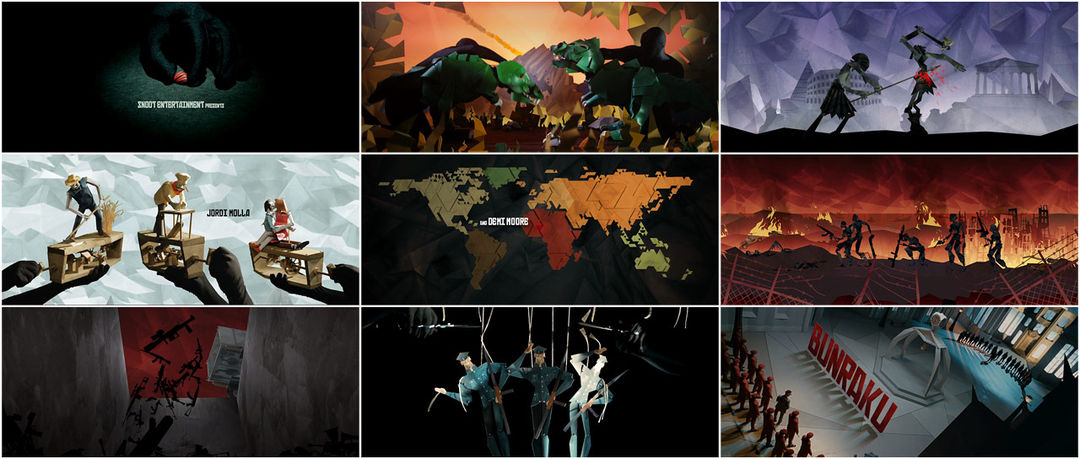

A solitary shell placed carefully by dark hands sets the stage for a bunraku play of prehistoric ages past: papier-mâché cephalopods give way to darting sea creatures and lizard beasts locked in combat. Humanity is introduced as the style changes to the two dimensional and animated cave paintings begin to slaughter one another with newly discovered weapons. Time progresses further and mankind’s weapons grow increasingly efficient, requiring less and less effort to kill and maim.

Utilizing varied styles of stagecraft to denote each passing era and narrated by a deep and commanding voice, Guilherme Marcondes’ title sequence for Guy Moshe's Bunraku brings us forward to the time of our story. A tyrant strides forth with his axe and an army stands in formation.

A discussion with title sequence director GUILHERME MARCONDES at Hornet.

Can you give us a little background on yourself—where you started and where you are now?

GM: I’m originally from Brazil, where I attended architecture school. I didn’t go to design or art school, but I was drawing a lot and I thought I’d be an illustrator. Eventually a friend who owned an animation studio called Lobo hired me as an intern and I absolutely loved it. One of the owners saw my drawings and offered to help me make a short film. It was a dream. I worked really hard and then they hired me. I stayed there for five years and that ended up being my design school. There were a lot of young people—it was the early days of motion graphics as we now know them. All these companies were in their early days, like Brand New School, Psyop, Motion Theory, and MK12, and we loved it all.

Guilherme Marcondes' short film Tyger

I left there in 2005 and started freelancing immediately, living in London to work with MTV and then went back to Brazil. One company really wanted to keep me so they offered to help with my Tyger short film project. Meanwhile, someone from Motion Theory visited Brazil for ResFest and we ended up meeting. They invited me to join the company and that’s when I decided to move to the U.S. At the same time, I finished Tyger, which blew up and went to all these animation festivals. It was a great time. I moved to LA to work for Motion Theory, but I stayed for only a year—it was hard to get back to a full-time schedule. I liked it there a lot, I was just—I wanted to do something by myself. Then I signed with Hornet and have been with them ever since. I moved to New York three years ago.

How did you first become involved with this project?

One of the producers of the film, I believe it was Nava Levin, came across my work online. Tyger had gotten great exposure and it featured Bunraku-style puppetry. Guy Moshe, Bunraku's director, invited me for a chat and we got along well. He showed me what he had already developed for it and I thought it was really interesting, but it's not the most exciting thing in the world to be invited to recreate something, so I was a little uncertain. I said, “I’m interested in doing this if you let me do some story-telling as well—I don’t just want to be a technical guy, accomplishing your vision.” I mean, of course it is his vision but I wanted to bring something to the table myself as well. I wanted to know how much creative freedom I would have so I wouldn’t be stuck repeating my short film all over again. He was very happy to let me do it. He was very receptive and that meeting went really well.

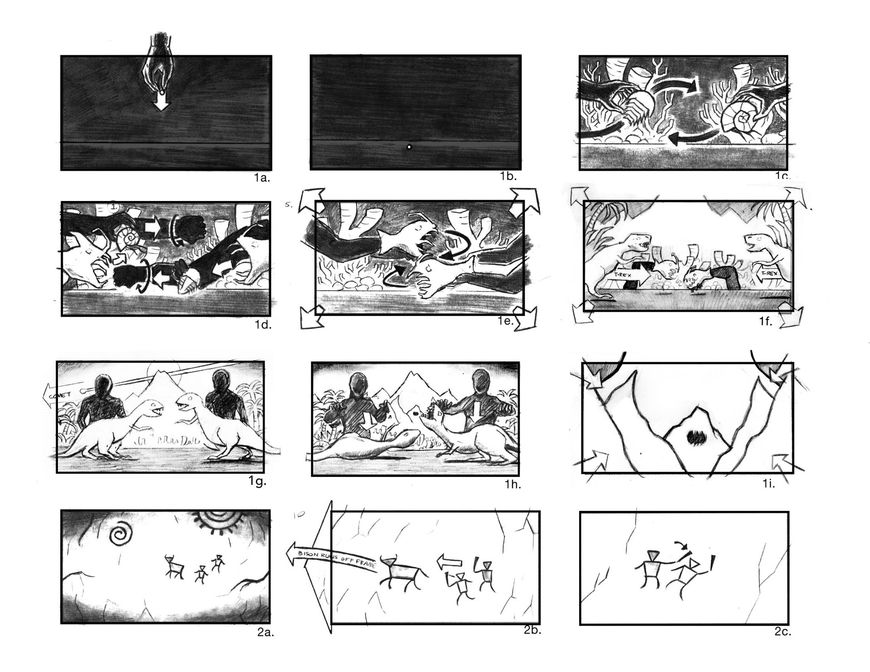

Original storyboards

So, what year was this?

This was early 2008. We started working on the opening before he had even started shooting the film! It probably wasn't the smartest thing to do but at the time we were all thinking of it as a part of the bigger picture—he didn’t want it to be just titles. Guy treated it more like an opening short film before the film. Initially, we didn’t even have the names of the actors or anything in there—he wanted it to be just an animation piece explaining the back story—because the concept was this crazy post-WWIII world where guns are banned and you know, there are all these things that you have to understand before the film starts. He wanted that to bring you into the movie.

In terms of the research materials, did the director have artwork that was specific for the opening titles or was it just for the main film?

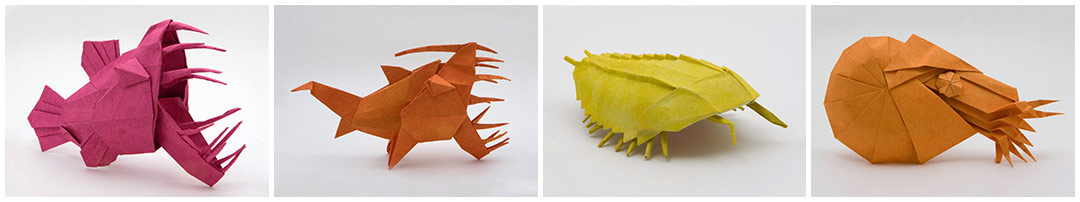

They had lots of overall research. They had research of the architecture, painting, origami photographs, and of course they had stills from films that were very theatrical. The film itself is shot with minimal backgrounds with a lot of stuff composed on top of it so it’s very gaudy, the colors are really strong. It’s a highly stylized movie and the action sequences are choreographed almost like dance acts. So, it was very unusual. They had their ideas for the whole world set up and then I developed the opening from that concept.

Origami models

The style partly came from Tyger but also some of that mix of origami and German expressionism which is very wacky but it was also what really sold me on the project. It wasn’t like I created that marriage of origami and expressionism—that’s something that came from their production designer Alex McDowell. But they seemed to be made to work together because if you look at German expressionism it’s all about straight lines and folds and the images are cut along different axes and when you look at origami it visually makes a lot of sense although culturally it’s so far apart. That was the main concept.

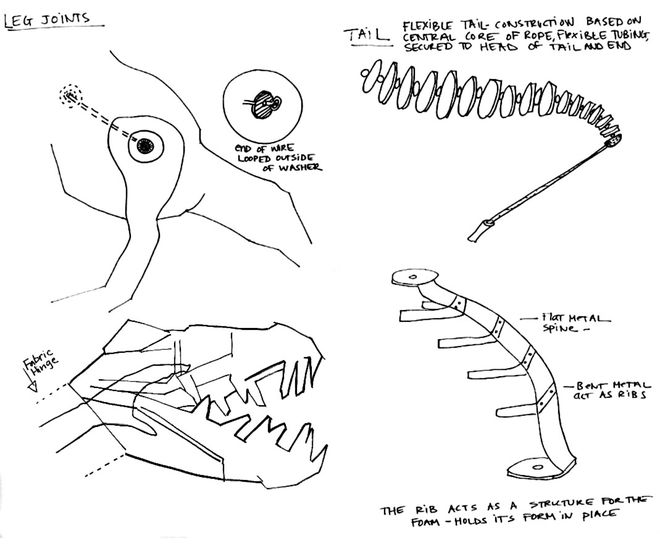

Dinosaur details

In terms of the script, did you have the voice-over material?

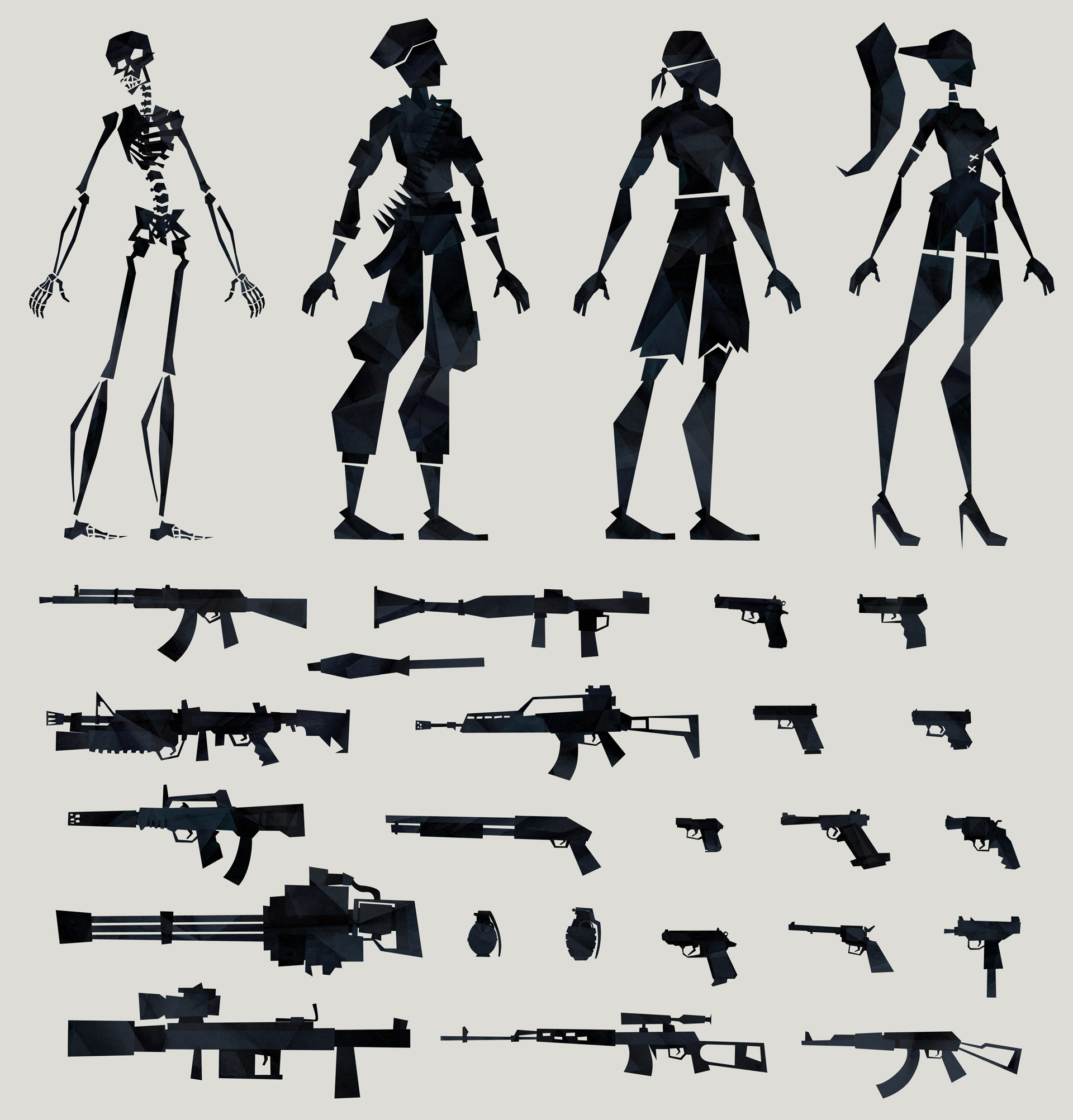

Not really. It changed a lot up to the last minute. I had rough texts and that’s how I started. I wrote down an overall concept. I wanted it to start with the theater and some very crude origami animals and for it to get more and more complex as it develops—a movement from simple puppets to more complex puppets to 2D animation and finally to 3D animation. Because the narration talks about the evolution of violence I also wanted the technique to evolve throughout the opening. It didn’t happen exactly like that but that was my initial vision—for the technique to reflect the evolution as much as the story.

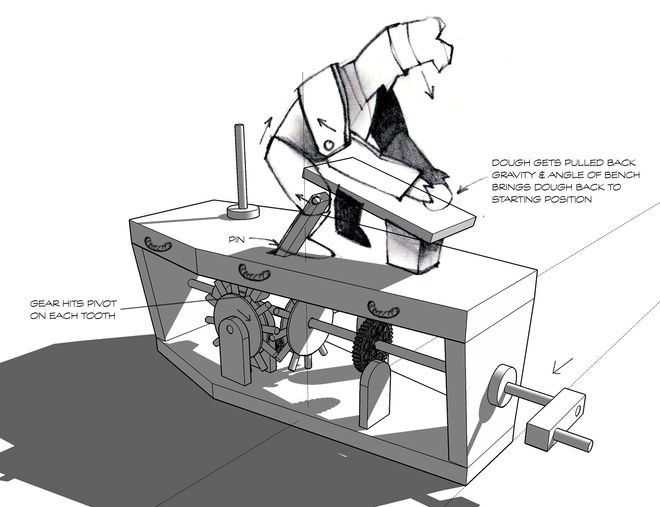

3D cut scenes

In the end I don’t think any of the 3D sequences made it into the final. In a feature film there’s this feeling, this pressure from all sides to make the opening as clear as possible and as audience-friendly as possible. Guy thought it was really important that people understood the story first and were amazed by the graphics second, which I think in the end was a good thing. It was painful at times because we had to throw out a lot of work, but it was a good challenge.

How big was the production team?

There were a lot of people on and off, contributing little bits, but I think the total team was about 20-30 people. I don’t know exactly because there was both a live-action team and an animation team and the project started in 2008 and finished in 2010, so sometimes people left. And there were freelancers.

Set building, puppet tests and puppeteering

How did you decide on the ratio of the puppetry to 2D animation and to the 3D you had at one point—how did you figure out where you wanted to see each of those techniques?

Roughly, I wanted the puppeteering parts to be non-human, so when the narration talks about death, violence, the primordial drive, and things like that. When it gets to human beings, the evolution of civilizations and the development of weapons, I wanted to shift over to 2D animation. Then when we got to the present time I wanted it to be all 3D, which didn’t end up happening. They were starting to get a little worried that there was too much technical showing-off which was detracting from the story. I wasn’t happy at the time, but eventually I thought it worked better—it forced me to tell the story with more clarity, so that was good.

Character designs

In terms of puppetry and animation, did the two teams work separately or together?

Separately, because the nature of the production was completely different. We had one pre-production team for the live-action puppetry and then we had the 2D team for the animation. First, I started doing the animation myself and then more people joined. Early in 2008 I gave the director, Guy Moshe, the treatment and we started storyboarding. There was a little back-and-forth and eventually we signed off on them in the spring of that year. Then we started on the pre-production for the shoot in summer 2008. So, the shooting of the puppetry coincided with the shooting of the actual film. We finished the live-action, and then we started some post-production on that and on the animation. We started having some conflicts between what the film was going to be and what the opening would contain. So, we had to put the project on hold for a good…I don’t know…maybe six or eight months, something like that. Because he really needed to have a first cut of the film, so that he could judge what would happen with the opening.

Baker, farmer and Lovers automation creation

Then we came back to the project almost a year later. We started doing the second round of the animation, and things kept changing. We put it on hold again. Then another edit. Then we made a final decision and went back to animation and we finished it early last year. So we started in 2008, and it was on hold for most of 2009. By the end of 2009, we got back to it. We finished in early 2010. Then the film…they were still finishing the editing and post-production! It took a while to get the distributors on board. Finally, the film is out where we can all see it!

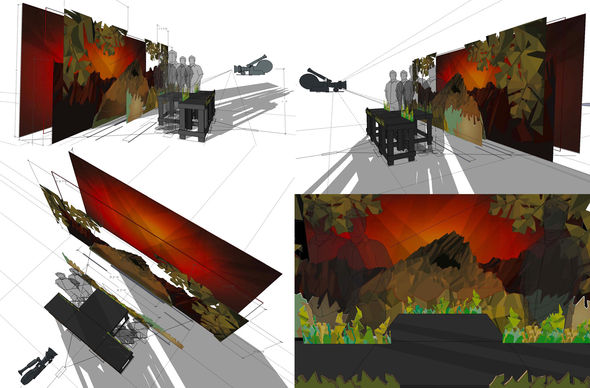

Set design previs

It was crazy. You work so hard on these things and you start to fear that you are never going to see it come together. It's so much back-and-forth, and it's so hard to get distribution. If it was hard for us, I can only imagine how hard it is on the director of the film itself. You put so much work and so much time in! Then after the work is done, it’s almost like it has really just started because you have to start publicizing the thing and trying to get a distributor and all that. It's a lot of production for not such a big budget. It's very ambitious. The opening was very ambitious, [laughs] and the film itself was very ambitious.