This article is part of a collaboration between Art of the Title and Kill Screen, celebrating video game title sequences and the artists who made them happen.

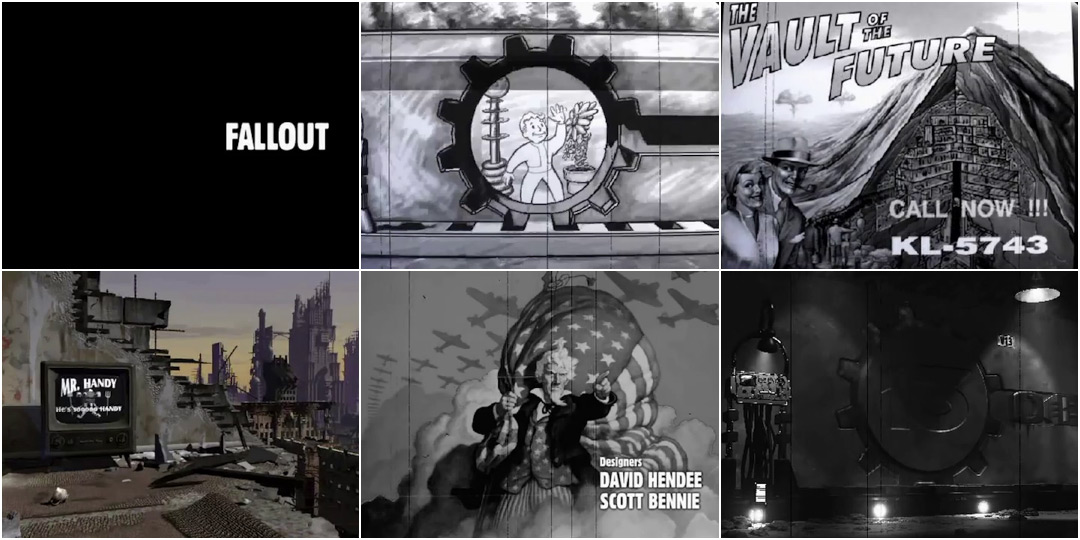

“FALLOUT.” One word in block letters, set against a black background. The crackle of a needle dropping on a vinyl record starts up; a black-and-white animation emerges from the wavering void of an analog TV signal. We see propaganda broadcasts rendering the apocalypse in determinedly cheery tones. Then the camera starts to pull back, the TV still going, to reveal the blasted-out husk of an American metropolis. The record starts to skip on the word “maybe” – an infinite halting loop of possibility – and the screen fades to black. Like an irradiated cockroach, the post-apocalyptic role-playing series Fallout has persisted through nearly 20 years of sequels and spin-offs. But its kitschy, retrofuturistic appeal arrived fully formed in the full motion video (FMV) that opens 1997’s Fallout.

“War. War never changes.” This line, delivered by narrator Ron Perlman, has long since calcified into a meme. But here, over grainy, noisy monochrome images of nuclear war, it still has a grim power. The second half of Fallout’s intro does a lot of heavy lifting plotwise, but it also works on a more primal level; tapping into anxieties about nuclear destruction and the decline of the West. The series has never really broadened beyond these concerns, instead tunneling deep into the aesthetic Fallout established in its opening moments.

Fallout’s opening posits a brutal future built on the bones of humanity’s most idealistic imaginings: it’s the ‘50s caught on an endless skipping “maybe,” poisoned by the bile of war.

A discussion with Fallout Director TIM CAIN and Art Director LEONARD BOYARSKY.

Can you talk about the original concept for the title sequence and how it was developed?

Leonard: There really was no team meeting about the intro, other than Lead Technical Artist Jason Anderson and me sitting in our office deciding what it should be. How could we set up the game world in an interesting way? More importantly, how we could accomplish it?

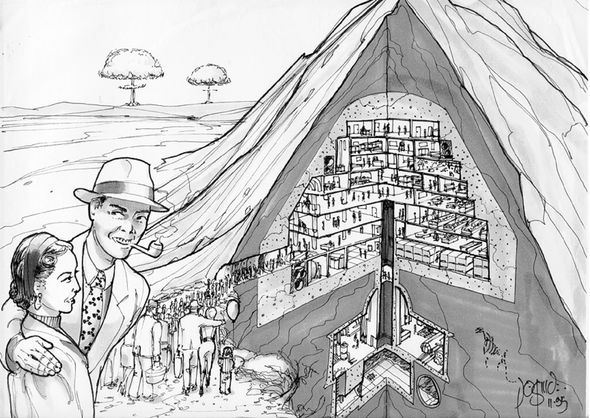

Fallout (1997) vault concept illustration by Tony Postma

Initially, I knew we wanted something haunting, something that would evoke a similar feeling to the end of Dr. Strangelove, when “We’ll Meet Again” is playing over the end of the world. That was pretty much what we started with – and from there all of our decisions were dictated by the limitations of the technology at the time.

In 1997, it was near impossible to make decent-looking people in 3D that would hold up to close scrutiny, so our first decision came out of that – that we’d put the whole thing on a TV screen that the camera was pulling away from. That led us directly to the end reveal. The whole thing took shape within minutes of those initial decisions – we had the tone and overall feel, and then we just made a list of that we wanted the scenes on the TV to be.

Tim: My contribution to the title sequence was mostly just the narration by Ron Perlman. When I wrote that, I suggested to Leonard that we show scenes from nuclear war and the preparation for those battles, but rendering all of that proved impossibly beyond our budget. But Leon came through with those awesome photographs from World War II, and combined with what we did render, it looked great.

Was there anything that took you by surprise when working on the opening?

Leonard: The most interesting thing for me that we hadn’t originally planned for was the guy getting executed. It was just going to be a shot of power-armored soldiers in combat, but, when I started working on it, I felt that there needed to be more happening in the scene and it just grew from there.

Fallout (1997) T-51b power armor render used for the box art and opening sequence.

Leonard: On Fallout, we constantly kept pushing the dark humour contrasted with violence, and that scene just kept evolving along those lines as I developed it. First it was just the contrast between our “dedicated boys keeping the peace” and the execution, then the second soldier laughing, then the waving at the camera. Like a lot of the game itself, we were just going on gut instinct much more than detailed planning.

How did The Ink Spots come onto your radar? Their music is inseparable from the Fallout vibe.

Leonard: I was looking for music to help achieve the mood we were looking for, and one of our artists, Gary Platner, brought in The Ink Spots’ “I Don’t Want to Set the World on Fire’, and we thought that was great. It was a bit too on the nose, but we liked the feel of the song as well as the joke, so we were going to run with it. However, we couldn’t afford it, so we began going through a huge library of songs from the ‘30s to the ‘50s, until I came upon “Maybe” – also by The Ink Spots. I could not believe how much alike they sounded; it wasn’t until later I realized that most of their songs were virtually interchangeable! Fortunately, it was within our budget. At this point, we had not yet changed the ending of the game. When we did, and added the song on top of it, it felt like we had planned it that way all along. It not only added more emotional weight to the end, but also made the intro seem even more haunting in retrospect.

It not only added more emotional weight to the end, but also made the intro seem even more haunting in retrospect.

Fallout (1997) end credits

Tim: “Maybe” fit the opening and ending of our game so much better. The line “maybe you will remember me” seems directed in the opening at the player from the old pre-apocalyptic world. But in the ending, that line is going from the player to his Vault. He helped them and they abandoned him, but maybe they will remember him. So tragic.

The Ink Spots were my grandfather’s favorite band, and he took my mother to one of their concerts in 1938 when my mother was only five years old. I didn’t know this when the opening title was made. In fact, I didn’t find out until a few months after Fallout shipped. I went to see my grandfather for Christmas in 1997, and I showed him the opening movie. He thought I had added The Ink Spots music just to please him and that wasn’t in the game itself. I told him the game shipped that way, and he was really happy.

What about this sequence are you most happy with?

Leonard: The whole thing, really. I feel like we accomplished what we set out to do, and I was very proud of the overall quality level as well as the effect we achieved emotionally – especially with our limited resources.

Image set: Fallout (1997) gameplay screenshots

Tim: I love how iconic they have become. They resonated powerfully with the viewers, and they really did establish the mood and tone of the game: violent and darkly humorous. Our team did a great job.

What are some of your favourite title sequences?

Leonard: There are too many great title sequences to name, but two movie intros that heavily influenced Fallout's intro are The Road Warrior and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, whose brilliant opening was “meta” before anyone even knew what “meta” was.

Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior (1981) main titles, designed by Optical & Graphic

Leonard: I think it's pretty obvious how we were inspired by The Road Warrior in general, but I loved the mythic quality the intro bestowed on the whole movie. That aspect of it – and how it was returned to at the end of the movie – not only inspired our intro, but also the ultimate end of the game, and even some of our initial designs for Fallout 2.

We didn't consciously set out to echo the mood from the Butch Cassidy intro, but when I saw it again, well after the fact, I realized some of the emotions I knew I wanted to evoke with Fallout’s intro had their origins in the effect that movie had on me when I was a kid.

Butch Cassidy And The Sundance Kid (1969) main titles, designed by Glenn Advertising, Inc.

Leonard: And, speaking of things that influenced us as children, we all know the best TV intro of all time was The Six Million Dollar Man.

Tim: For games, there are a lot of title sequences I love: Half-Life, Borderlands, Saint’s Row 3, and World of Warcraft all spring to mind. They established the tone and the look of those games so well.

As for movies, I think my all-time favorite is Alien. I think it’s the first time that a title sequence – just the font itself – seemed scary.

It’s the first time that a title sequence — just the font itself — seemed scary.

Alien (1979) main titles, designed by Richard Greenberg

Tim: When it came out, I was too young to see the movie alone, so my mother took me and my brother to see it. She watched the whole movie with her hands up to her face, ready to block out any scene that was too frightening, but my brother and I loved it, especially the meal scene. I don’t think my mother cooked spaghetti for a month afterward.

SUPPLEMENTARY: Fallout (1997) end credits easter egg – typing "boom" brings up an animation of Tim Cain's head exploding.