Once upon a time, in a far away land, a little girl lived deep in the woods. They called her Princesita.

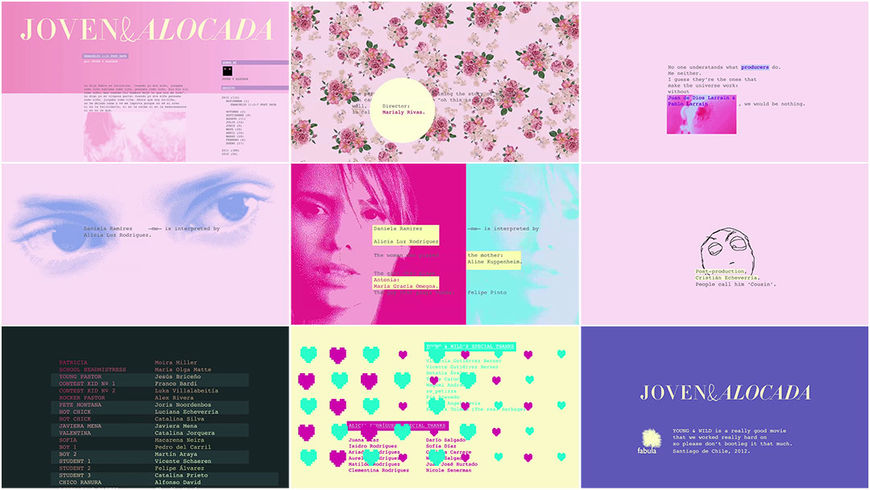

If this sounds like the introduction to a quaint, Disney-style fairy tale, it is anything but. Inspired by real-life accounts of secretive cults and the harm they can inflict, Marialy Rivas’s 2018 feature film Princesita twists the princess trope into a dark and dreamy bildungsroman. The follow-up to 2012’s Joven y Alocada (Young and Wild), a film about a young woman in Santiago with strict, religious parents and a scintillating blog, 2018’s Princesita centers on Tamara, a 12-year-old girl who was born into an isolated cult in the south of Chile. Tamara’s world is fueled by magic, myth, and the edicts of charismatic cult leader Miguel – until it isn’t. The film explores themes of purity, power, and patriarchy with a formidable deftness, presenting the story from the perspective of a child who is slowly but surely coming of age and emerging into the light.

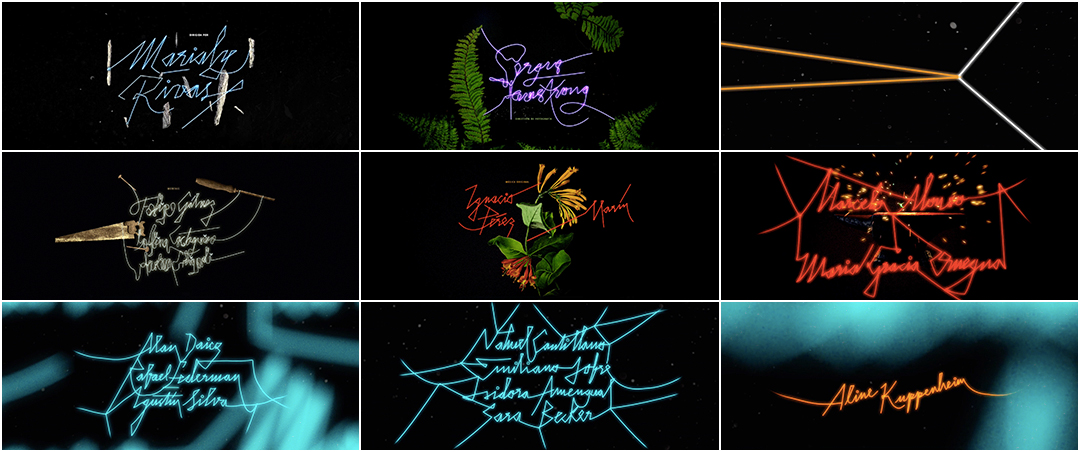

It is this idea of light and dark that is explored in Princesita’s gorgeous end credits sequence designed by Santiago-based studio Smog, also responsible for the titles of Rivas’s previous film. Smog Creative Director Pablo González and his team take an experimental approach that uses stock footage, string and hooks, rotoscoping, and digital effects, bringing together imagery of neon lights and sparks, hand tools, and the quiet, lush imagery of the forest.

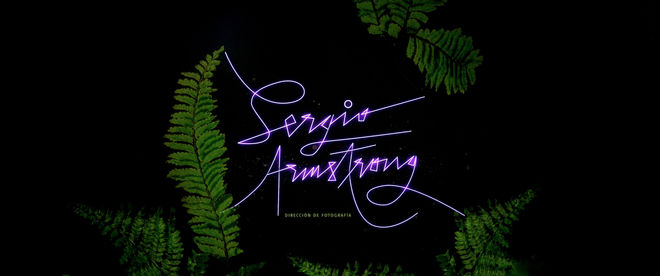

The glowing names of the cast and crew, created with string that was filmed and then digitally rotoscoped, is a real highlight. Its movement is delicate and awkward, bumbling into the shapes of names as stars spin, dust swirls, ants tumble, and ferns unfurl.

We talk to Rivas and González about the journey to making Princesita, the creation of the end title sequence, and how the film industry in Chile has changed in recent years.

A discussion with Princesita Director MARIALY RIVAS and Title Designer PABLO GONZÁLEZ.

Marialy, before you were a filmmaker, you worked in advertising. Tell me about that. How did you transition into film?

Marialy: This is the thing! From a young age I was into the arts but I didn’t watch TV until I was 20. I used to go to the movies three times a week, so I fell in love with the movies – deeply. The only thing I wanted to study was cinema. We didn’t have a cinema school at the time because they closed everything under the dictatorship.

—Marialy RivasThe idea came to me when I read an article in the newspaper in 2012. A lot of people thought the world was going to end then.

Director Marialy Rivas (center, with headphones) on the set of Princesita (2018)

Marialy: But in 1995 they opened the first cinema school where I entered with Sebastián Lelio, the winner of the Oscar for best feature in 2017.

Right, for A Fantastic Woman.

Marialy: Yes! So I did a short film, Desde sempre, in 1996 when I was 19 – the first short film about gay people in Chile – and I won some prizes. Then I went to New York because I had a scholarship to study film. When 9/11 happened, everything was extremely weird. I came back to Chile. I was 25 years old and I had no money because I was waitressing in New York. A friend of mine said, “Well, if you want, you can be my assistant.” He was doing commercials. I said okay.

DGT ad directed by Marialy Rivas

When I had been an assistant director for six months, an agency said, “We want you to direct an ad.” There was no other way at that time to even shoot. I thought: I will learn the craft. How to use a lens, a dolly, everything – to be able to do movies!

Marialy: Advertising, it was hard for me in the beginning. I didn’t understand the code because I never grew up watching TV. But it taught me how to shoot. Film is a very technical thing. So I was happy to know the technical side. I started directing in 2003. I directed the campaign for Michelle Bachelet, Chile’s first woman president, in 2005. Then I started to develop projects in fiction. In Chile, we only have one prize a year to make movies. So it took me a long time to actually win the money to make a film! [laughs] In the meantime I was shooting commercials and then in 2010 I did Blokes, the short film. We went to the official competition in Cannes.

Trailer for the short film Blokes (2010), directed by Marialy Rivas

Marialy: From then on, I’ve been doing films as well as commercials because films don’t pay the rent still. [laughs] I hope one day they do!

Pablo, can you talk about the film and animation industries in Chile? Have you seen a change since the success of A Fantastic Woman?

Pablo: There’s been a lot of change. With the Oscar for A Fantastic Woman the film industry is becoming more adult, more professional, more serious, unionizing and stuff like that. That is basically putting animation and film on the map for government funds. The amount of funding that animation has seen in the last few years is increasing. That makes people appreciate everyone on the chain more, so you get more requests for collaboration on titles and posters and other stuff. The industry in Chile is booming.

Marialy, was it easier to make your second film, Princesita? What was that journey like?

Marialy: Oof, it was a complicated journey. Mostly because the subject of the second film is a dark one. I see now how films infiltrate your life. When I shot Young and Wild, everything around me started to seem sexy and fun like the movie.

—Marialy RivasWhen I shot Young and Wild, everything around me started to seem sexy and fun like the movie.

Joven y Alocada (Young and Wild) (2012) end title sequence

Marialy: Then when I shot Princesita, a lot of abuse stories started to come out around me, from people that I knew, people that I love. I had the luck to not be near abuse in my personal life so when I started researching it, it was a very intense experience.

The idea came to me when I read an article in the newspaper in 2012. A lot of people thought the world was going to end then. In the south of Chile there was this family cult only composed by males and they had this girl with them, their niece. They claimed that this girl was the chosen one to carry the messiah that will stop the end of the world. It was striking for me. I thought, “How is it possible that these men don’t even consider what this girl wants?” For them, the girl was only a vehicle for their objectives. It seemed, for me, like a micro-story of the female experience throughout history. They are not valuable as themselves, as human beings, just valuable when they serve a purpose that a male needs them to serve.

—Marialy RivasTamara lives in this kind of fantasy world. She sees Miguel as a good guy but she can also feel that something is not right.

Stills from Princesita (2018)

Though it’s a dark tale, the film often has a gentle, magical and fantasy-like atmosphere. Why was that important to convey?

Marialy: It came from different sides. When I started interviewing women that were abused during their childhood, what astonished me was when they described their abuse, they have confusing memories and feelings. If a painting was in the room, they remember the painting. Psychiatrists told me it’s because the mind cannot wrap around the abuse. It’s too strong so they need to go to a different place. I realized that I needed to do something nightmarish. Also, all of these women were seduced as children by the abuser. Most of the time it is someone that the child trusts; the child thinks they are everything. Tamara lives in this kind of fantasy world. She sees Miguel as a good guy but she can also feel that something is not right. This is the experience that all these women told me. This was one side of it.

Another side of it was that the original girl, this family cult called her “Princesita” which means Little Princess. I started to think, This is a girl that is a princess that lives in the middle of the woods in a very far away land . . . It sounded like a Disney story but with a dark twist. So through all of these sides, the aesthetic came about.

Princesita (2018) opening title sequence

Both Young and Wild and Princesita have vibrant and energetic end sequences. What is it about this energy and colour that attracts you?

Marialy: With Princesita, I was thinking about how people are so interested in the surface of things. That interest is based mostly on aesthetics. People want to project an image. An aesthetic discourse will carry you much further than a manifesto of 100 pages, you know? Aesthetics seduce more easily than someone talking and talking . . .

So I started researching different artists and I went to an exhibit at the MOMA and I saw this installation with neon, this cross in a corner… and I thought, Okay, this is it. Then I arrived to this video that Lady Gaga did with Marina Abramovich that has a lot of things similar to what I finally put in the movie.

VIDEO: The Abramovic Method practiced by Lady Gaga. See more at the Marina Abramovich Institute.

Rainbow Neon Cross for Two by Jonathan Horowitz. Video by Gavin Brown.

Marialy: It was a research of different artists to arrive to an image of the cult. And from that, when I talked again with Pablo, I told him, “Here is the film.” For me, a film starts with the first frame and finishes in the last frame, and by that I mean also the titles! The film is the whole thing. You are already telling something with the titles, at the beginning and at the end.

Pablo: They do tend to have different requirements, title sequences. Some throw you into the world of the movie or some need to tell you background facts. For this it was basically about creating mood.

Stills from the Princesita opening title sequence

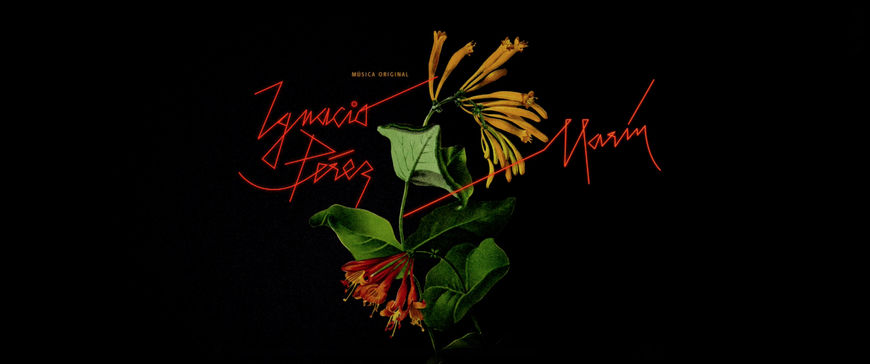

Marialy: I told Pablo that I needed to convey the feeling of a fairy tale but I also wanted it to be “pop”! We discussed fairy tale books, how at the start they usually have this big first letter of the word, that has flowers or whatever? So then he worked on the title, on “Princesita” and he came up with the idea of doing all the titles with this neon type of credits. He wanted to add flowers and moving little butterflies and plants because she lives in the woods. I said, “This is great!” From that image, he developed the whole.

Pablo: I didn’t want the sequence to look like it was basically grabbing things from the movie and throwing them onto an After Effects timeline. I wanted to create an imagery of its own for the sequence.

—Pablo GonzálezIt’s okay to use stock imagery and flowers, it’s just about how you use it.

Stills from Princesita end titles

Marialy: He did the typography, he used different textures, looking for the perfect one, and he ended up doing it with string.

Pablo: Very important in the concept of the neon strings was that double-cross the community had as a symbol. I wanted to use something that felt like neon but not exactly that. The end of the movie is dark as night. That was an important starting point. We couldn’t make too drastic a change. It was really about light. The whole conversation of the title sequence is about light. Light and darkness. That fight. The initial idea was that we would see a transit from night to day in the ending sequence. The neon strings would lose brightness. In the end we just made a contrasting card for Sara Caballero, the star actress, by using the spark.

Stills from Princesita end titles featuring Sara Caballero's credit

Pablo: I didn’t have an idea of how we are going to actually do it. We did a lot of testing. We simulated strings on 3D and we tried to animate it by hand in After Effects. We ended up filming the title designs. We would have like, a cardboard with pins and we would recreate the design and untangle them in front of a camera. We ended up rotoscoping that. It was so painfully long, that process, but it was really worth it. The result was very interesting. It’s funny that it was so handmade.

Reference shoot for string credits using cord, nails, and a board

Reference shoot with strings for Gutierrez credit

Reference shoot with strings for Camila credit

Pablo: It had so many layers: dust, light, 3D elements. There’s so many things that need to co-exist in that space. It’s very different to the work we usually do at the studio so it took extra testing. We are a very small studio so there’s a lot of multi-tasking. It’s not like we have one person that specializes in light and one that specializes in string animation. We just have one generalist, Marco Lizama, a 3D artist, who did a lot of the heavy lifting.

Rotoscope test on credit for Camila

Animation test on credit for Marialy Rivas

The bark, the butterflies, the flowers – these are all stock footage, right?

Pablo: Yes, we grabbed photos from stock sites and used them as maps for 3D geometry. Most of them are recreated in 3D. The images come from the idea of the forest. Other than the reference strings, we didn’t shoot any of the elements. The dust particles that float are filmed by us but not the elements, the flowers opening and such, that’s stock timelapse. They’re not trying to hide or anything – it’s okay to use stock imagery and flowers, it’s just about how you use it.

Stills from Princesita end titles

What tools and software did you use? How did you animate and what did you use to add texture, to colour grade?

Pablo: It’s mostly After Effects and some 3D elements are Cinema4D. All the compositing, animation, rotoscoping is Photoshop and After Effects. This was a very experimental piece for us. We really went out of our comfort zones, we went very out there.

Stills from Princesita end titles

Do you have favourite title sequences? Ones that inspire you?

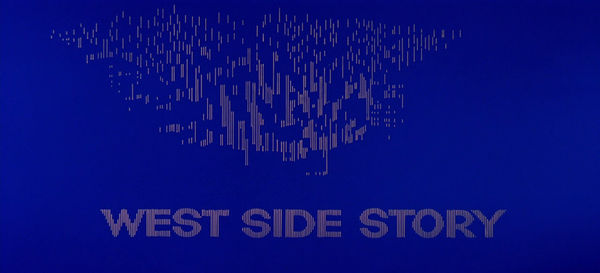

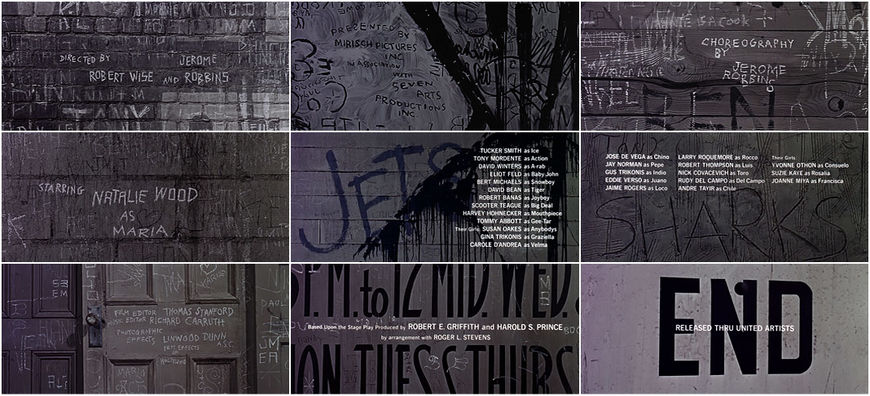

Marialy: One of my favourite movies is West Side Story. I think they have a very interesting way of putting the titles at the end and also at the beginning, with all that colour changing and how all the lines become New York. That amazing first shot. At the end the titles are on the wall, on the bricks, the gang wrote over them. In that movie, you can see that [attention to detail] from beginning to end. This is something that I have always admired.

West Side Story (1961) opening prologue and title design by Saul Bass and Elaine Bass

West Side Story (1961) end credits sequence designed by Saul Bass and Elaine Bass

Pablo, do you have favourite titles these days, things that have been exciting to you?

Pablo: I’ve found myself very bitter on that front, actually. I’ve been seeing shows and thinking, like, “Agh. That was a lame sequence.” No. I don’t think the title sequence business is very exciting anymore. [laughs] My good angel on my shoulder right now is saying, “What are you saying, man?” But it’s true! Title design is an industry that people are getting more interested in but people are not willing to pay for the amount of work it is! Making movie titles is a ridiculous amount of work. You’re not working for a client that wants to increase sales, that has specific goals in mind. You’re working with an artist on their art piece. It’s tough for them to open up, to make space for you to do your work.

I hear that a lot. Title design is generally not something designers do to pay the rent.

Pablo: That’s where I’m coming from and saying that I’m fed up with it. On the other hand, you get to do these crazy, sometimes beautiful things but it takes so much more energy than regular animated motion pieces.

So what is the benefit of making a movie title sequence? Why do you do it?

Pablo: It’s a fantastic question. At the end, you are very happy you made it. I don’t think title sequences are fun to do but they’re great to have made. I get goosebumps when I see them on the big screen and no other thing that we make do you get to see 16 meters wide. You just don’t. They’re very specific conditions that movie theatres create. You are whispering into people’s ears in a dark room with a massive screen with no interruption. It’s amazing to see them ready and done. That’s why we do it.