The viewer is greeted by an eerily empty theatre – dark, desolate and silent. Suddenly, a shuffling of feet, a startled pigeon, and our main man hobbles into the spotlight, sparking an explosion of sound.

As ringleader Ian Dury, Andy Serkis is obscenely hypnotizing, his eyes rolling about as he hunches over the microphone, satirical and lyrical in that “Mockney” accent. Serkis, best known for his performance capture roles as Gollum in the Lord of the Rings and Hobbit films, Captain Haddock in Steven Spielberg's The Adventures of Tintin, and others, here deftly captures Ian Dury's frenetic energy.

As well as being lead singer of The Blockheads, Ian Dury was an artist and actor who rose to fame in the 1970s, during the punk and new wave eras. The film, titled after Ian Dury's 1977 single of the same name, is an attempt to bridge the gap between the general public and Ian – to bring attention to a man often misunderstood – in a vibrant mélange of colour and movement. Often misinterpreted to this day, the song "Sex & Drugs & Rock & Roll" aims to offer listeners the option of alternative lifestyles:

Don’t do nothing that is cut-price

You know what they'll make you be

They will try their tricky device

Trap you with the ordinary

Get your teeth into a small slice

The cake of liberty

And so the title sequence presents a variety of styles and approaches: the starry backdrop melds into pop-art animation, Peter Blake’s hand-written typography trembles, and the scene oscillates between the raucous stage show, band practice, and a birth. Buffeted between public and private, the sequence is at once disorienting and cohesive, ultimately underlining Dury’s unofficial modus operandi of boldly turning life into art.

A discussion with Creative Director MATT BATEMAN at Flat-e.

Give us a little background on yourself and Flat-e.

MB: Flat-e is a London-based studio. We make films and animation for music promos, advertising, feature films, and live events. I’ve worked with the studio as a creative director and animator since its conception in 2002.

And how were you first approached about Sex & Drugs & Rock & Roll?

I was initially contacted by Richard Bullock, the film’s production designer. I had previously worked with him on the film Bunny and the Bull as an animator and back projection designer. Richard and Mat Whitecross, the director, had initially discussed using back projection for the title sequence and after our initial meeting it felt like we were on the same wavelength. Later, we decided against back projection although we did approach the sequence with that aesthetic in mind. After that, we arranged a meeting with Sir Peter Blake and began to sketch out ideas from there.

Sir Peter Blake artwork examples

Did you already know you wanted to use footage from the film? Was the film already in production?

No, and a great deal of planning and consideration had to be taken before any shooting took place because the title sequence transitions between filmed footage and animation. We had a pretty good idea of the sequence in the days leading up to the shoot. The closing credit sequence didn't begin to materialise until well into the production process and, for a while, we didn't have any idea of how it might work.

What was the timeline for the project?

We began discussing the animated sequences before shooting started in April 2009 and we finished in November of the same year. This involved multiple animation sequences in the film, as well as the front and end credits.

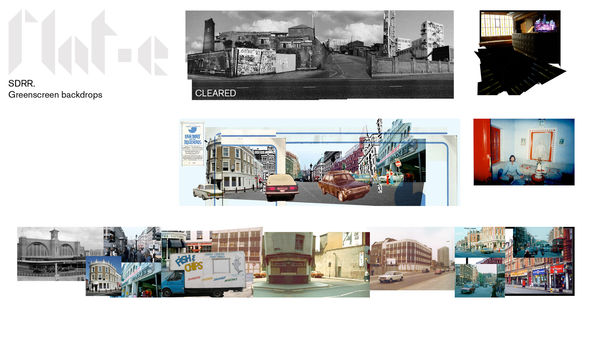

Backdrop concept board

What were the initial design stages like? How many different concepts did you go through?

Regarding the main title sequence, the initial meetings with Mat, Peter, and myself were very open and relaxed. We talked about Ian's life and career and Peter's memories of him, since he taught Ian painting at the Royal College of Art in the 1960s. Mat already knew he wanted the opening to be based around a live Ian Dury performance, but also wanted to introduce a Blockhead version of London.

So we would transition between the live performance, the birth of Ian’s son Baxter, and the scenes of Ian and Russel driving to a gig. I took a variety of photos of the van and did some initial animatics of how I thought the animation could work. Once the shooting was done, Mat took the animatics and edited a rough cut of the whole sequence. These initial timings became the basis for the finished product.

Driving scene animatic

Talk about the research and references that went into the sequences.

The early stages of the project were very inspiring. We pulled elements from all over the place: Richard's set designs, Peter's archive of art, and my own designs.

Peter's personal archive is vast, so getting the opportunity to have a guided tour was unbelievable! We began sharing imagery and ideas with which to populate the animated version of London.

Set photos

We were drawing from all aspects of the art, design, and animation of the time. I specifically remember Mat showing me the original video for the Beatles song “Eleanor Rigby” and some early Terry Gilliam sequences. There is a definite charm in those animations which we tried to draw on without making it too much of a pastiche.

Also, Peter's daughter Liberty had a personal collection of Blockheads memorabilia which was extremely useful, particularly the illustration by Ian Dury that became the catalyst for the end credits.

We placed his music, performance, and painting within the first few minutes to help establish the breadth of his creativity. For me, his paintings are a visual echo of that creativity. The bright colours and textures seemed perfect to finish the film with and the illustrations provided a perfect framework with which to show the cast.

Ian Dury collages and end title treatment

Talk a little about the collaboration with Sir Peter Blake – how did it transpire? How did it evolve?

After initial discussions and reference swapping, Peter set about creating a type treatment for the main title. He visited our studio on a number of occasions where we would look at how the type was developing and insert it into the sequence.

Then, he would comment, make notes, or suggest changes. He would also bring materials from his archive which were scanned and used to build our mixed media, pop art vision of London. His approach was very deliberate and considered, which was inspiring to see. For me, I grew my practice working with computers and tools where things are infinitely changeable and trial-and-error is a large part of it. But Peter would do it differently – he’d think long and hard about decisions regarding colour or composition before physically committing to them. Strangely, although it would feel slow and leisurely, we would achieve a lot in our sessions together which is testament to his great talent as an artist.

Main title treatment

What was it like working with the director, Mat Whitecross?

From the first meeting with Mat, it was clear that he not only had a vision for the title sequence and animations in the film, but that he wanted to collaborate. Mat has an unbelievable energy and he was often on hand to help with questions regarding the work we were doing, which included some very late night visits to our studio. Even though he was very much involved, it still felt like we had plenty of freedom to come up with things that were personally satisfying. I think this was because our initial meetings were so warm and open and I had a good understanding of what he wanted.

Which tools and software did you use to put it all together?

We used Adobe CS with After Effects for the animation. We also used many non-digital tools: hand-drawn typography, inks, paints, felt-tip pens, and photocopies.

And finally, what is it about Ian Dury that drew you toward this project?

Ian was an inspiring character. I was acquainted with his music before the project but knew little of his life, so when I was first contacted about the job, I began to watch some of his live performances.

"I Want To Be Straight" (1980) music video

He had such an amazing stage presence: confident, understated, at once raucous and calm. This, combined with his extraordinary talent as a songwriter, completely hooked me. He was also a very visual person so the way he dressed and the style of his paintings gave me plenty of inspiration.

The footage we filmed with Ian and Russel in the van shows them on the way to a gig sometime around 1974. London at this time was quite a grim place – the Three-Day Week was being implemented and the economy was in serious trouble.

The Three-Day Week was one of several measures introduced in the UK by the Conservative Government to conserve electricity, the generation of which was severely limited due to industrial action by coal miners. From January 1st until March 7th 1974 customers were limited to three days of electricity per week.

Despite this and dealing with his disability, Ian saw the world in such a colourful way. In a BBC interview, he was asked whether living with a disability affected his life. He replied,

“Although I'm severely disabled in some ways, I'm not restricted that much by it. I can't run for buses but I don't really mind missing a few buses.”

End Credit sequence