The Exorcist was not your average blockbuster film. Called “the greatest horror film of all time” by many, it has remained unparalleled in terms of its initial reception, its cultural impact and its subsequent adoption into the American film canon. With a worldwide gross of over $440 million, countless magazine covers and Evangelist preacher Billy Graham proclaiming “the Devil is in every frame,” it was a phenomenon. On its release Variety called the film “pure cinematic terror” and the New York Daily News proclaimed it “a brilliantly successful horror movie.” Pauline Kael, writing for the New Yorker, grudgingly admitted that, “The Exorcist is too ugly a phenomenon to take lightly.”

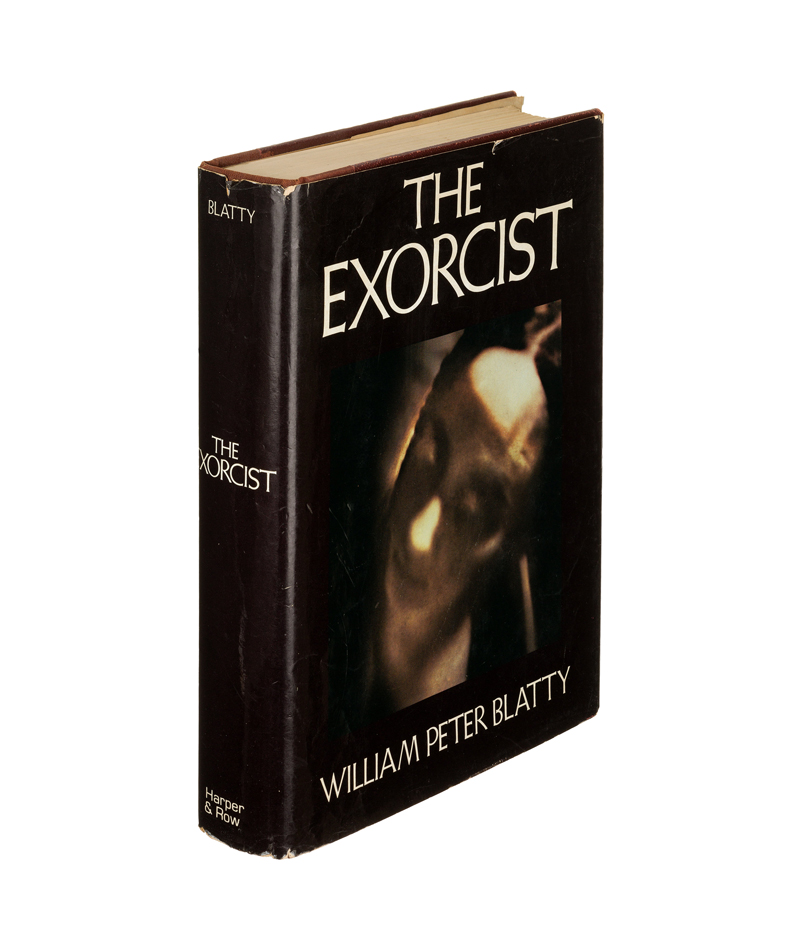

Based on William Peter Blatty’s book of the same name, The Exorcist was inspired by an account of a real-life exorcism Blatty had heard of while attending Georgetown University in 1949. It would take him another two decades to write and publish the book but, remembering the incident which inspired it, he decided to use Georgetown, Washington as a setting for the screenplay.

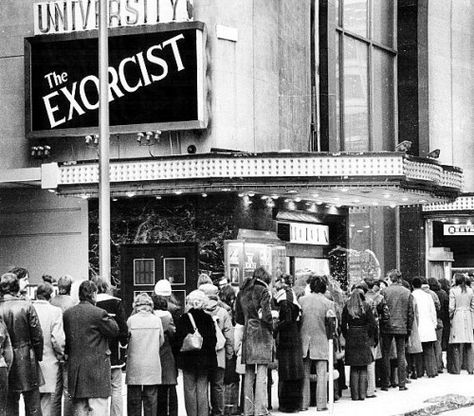

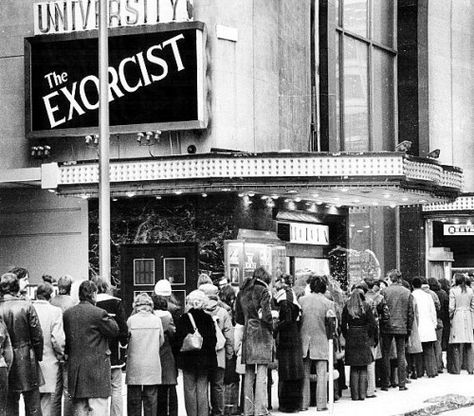

Patrons line up in record numbers in freezing temperatures outside a theatre in Toronto, Canada, in January 1974 to see The Exorcist.

Both the book and the film follow elderly Jesuit priest Father Merrin (Max Von Sydow) who, while on an archaeological dig in Iraq, uncovers an ancient amulet.

Merrin, who is no stranger to performing exorcisms, is immediately fearful and wary of an impending confrontation with its owner, the demon Pazuzu. Meanwhile in Georgetown, a young girl, Regan MacNeil (Linda Blair) becomes possessed. Her mother Chris (Ellen Burstyn) tries multiple medical interventions but comes to believe that her daughter’s ailment is spiritual rather than physical. She requests the help of Father Karras (Jason Miller), a young priest going through a crisis of faith. Eventually the Catholic Church agrees to let Karras perform an exorcism under the condition that a more experienced priest help. Enter: Father Merrin.

Still from The Exorcist showing Father Merrin and the Pazuzu statue

When we first encounter Merrin in Iraq, he is not in his robes. A young boy runs to find him and reports, “They found something… small pieces.” When Merrin investigates, his colleagues tell him they have found arrowheads and coins. Merrin peers further into the small opening in the rock and uncovers an amulet. It is an amulet which, depending on your interpretation, puts the narrative into motion or acts as a warning to Merrin that something is already afoot.

Still from The Exorcist showing the discovery of the Pazuzu amulet

What an excellent day for an exorcism

The novel was a bestseller when it was published in 1971 and soon Warner Brothers came calling for the rights to the book. Blatty would stay on to write the script of his novel while Warner Brothers courted most of the hot-shot directorial talent of the time, both in Hollywood and abroad. Blatty, however, was insistent on William Friedkin, who was just coming off of multiple Oscar wins for his first film The French Connection (1971).

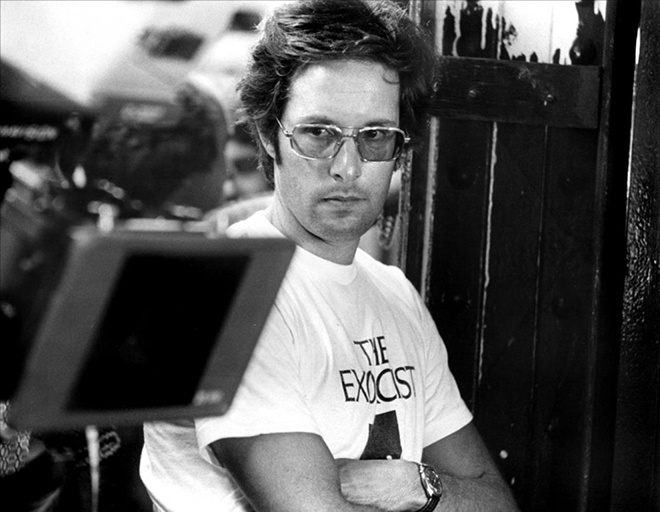

Director William Friedkin on the set of The Exorcist

After much back and forth between Blatty and Warner Brothers, who were interested in directors such as Stanley Kubrick and Arthur Penn, Friedkin was eventually given the reins to The Exorcist, igniting a contentious relationship between Blatty and Friedkin, as well as a storied and troubled shoot.

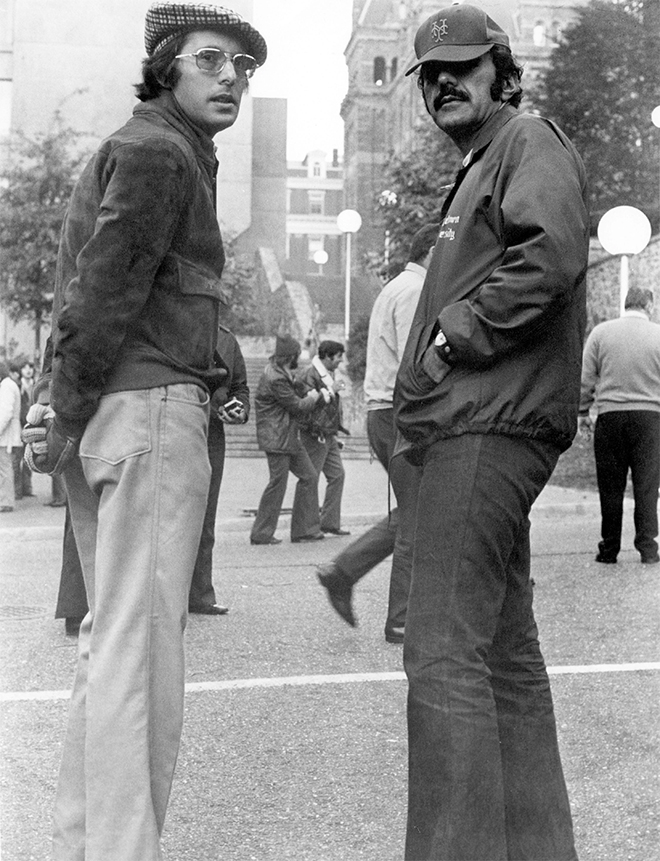

William Friedkin and William Peter Blatty on the set of The Exorcist.

Credit: Alamy

Blatty was a practicing Christian while Friedkin was an agnostic, causing tension on how firmly the film should be entrenched in a religious gaze. The Exorcist is a rare film that holds on to these competing viewpoints, allowing the film to become its own creature. It is a contemporary religious film because it does not uphold the minutiae of religion but instead explores more universal themes of faith, forgiveness and redemption.

I'm the devil. Now kindly undo these straps!

For title sequence designer Dan Perri, The Exorcist was an important milestone: his first major studio job. Perri would go on to design titles for films such as Star Wars (1977), Raging Bull (1980), Insomnia (2002), The Aviator (2004), and Suspiria (2018), among many others.

Title Design: The Making of Movie Titles (2016) featuring Dan Perri

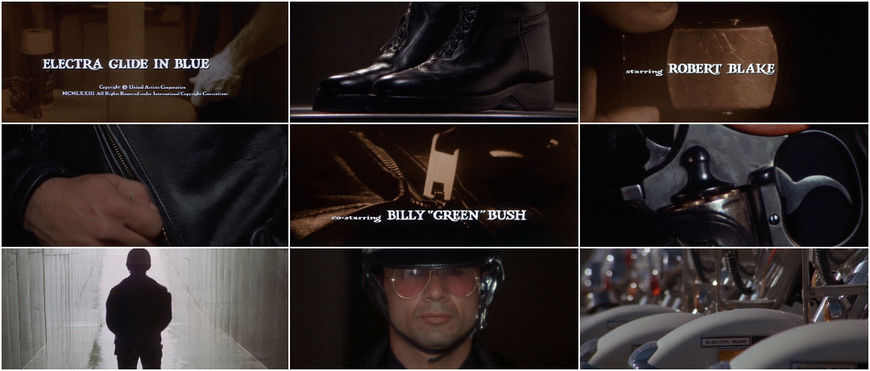

He was asked to join the Exorcist production after Friedkin saw his work in another film. “Billy [Friedkin] invited me to work on the film after seeing Electra Glide in Blue,” remembers Perri. “Then about a year-long experience began, working with him on The Exorcist as he was busy editing and re-editing it.”

Electra Glide in Blue (1973) main titles, designed by Perri & Smith

With the prologue of the film taking place in Iraq, outside of the larger narrative, the world of The Exorcist immediately opens up and becomes bigger than the fight for the soul of a twelve-year-old girl in modern-day America. When Friedkin’s director’s cut was theatrically released in 2000 several elements were added such as the infamous “spider-walk” sequence and a more subtle shift in the first moments of the film. After a brief glimpse of the MacNeil house and the soon-to-be defaced church statue, the credits appear and the shrieking string music changes to a man’s voice chanting as “The Exorcist” appears on screen.

The Exorcist title card

“It took a long time to design the simplicity of what we wound up using due to experimenting as the film changed shape. As [Friedkin] was tightening and evolving the story it would affect how the opening took place,” says Perri.

“When Billy [Friedkin] played me the music he was going to use over the titles, that pushed me further. The simplicity of the titles is in the delicate handling of all the elements. On screen, the fewer the elements, the more important each becomes. So we’re dealing with two elements: a screen that’s black and type, the name of the film. How those two words interact, the size relationship, the size on the screen, the placement, how it enters the screen, all those things have impact and those are all part of my process.”

Captain Howdy said no

It was a well-known fact that Friedkin and Blatty were not getting along during filming, and the design of the titles reflected that tension as well as certain legal obligations. “The two credits that precede the main title have to announce the director because it’s his film, and then the writer’s connection to the film,” explains Perri.

“It’s ‘William Peter Blatty’s The Exorcist’, it’s his possessory, but then it’s ‘A William Friedkin Film.’ There are legal guidelines as well; their names had to be the same size but where Bill Blatty has three names, of course they had to be the same size. ... If you look at the Friedkin title next to the Blatty title, the Blatty title looks bigger because it’s three names and two lines, whereas Billy’s name is ‘William Friedkin’ in one line. I could have stacked ‘William’ over ‘Friedkin’ the way I stacked ‘William Peter’ over ‘Blatty’. When I showed these to Billy I probably showed him a version where both their names were stacked similarly and the version we wound up using, which gave him distinction as being arranged differently than Blatty’s name.”

This cuts into a black-and-white sun which slowly suffuses with colour. The audience is confronted with a familiar image – the sun in the sky – but its slow bleed into colour gives this early moment an otherworldly feeling – possibly something unnatural, something coming alive.

“[Friedkin] came to me at one point and said, ‘I want to have a sunrise to open the film and establish the Northern Iraq sequence’ which he had shot the year before. And he said, ‘But I didn’t shoot a sunrise.’ The image he had was the sun in the sky. It was midday, hot, with ripples of heat going through the frame. I suggested that we create an implied sunrise and that’s what’s in the film now: a very, very long fade in, like a 30-second fade in of the sun in the sky but in black and white. It very slowly dissolves into colour."

"That emotionally gave us the feeling of the day beginning, the movie beginning, the story beginning," says Perri. "So it solved the problem.”

The power of Christ compels you

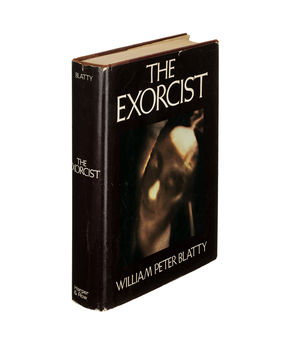

Cover of The Exorcist first edition

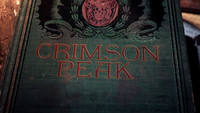

And what of the iconic typeface that has carried The Exorcist through its multiple reissues and re-releases? Perri kept the font used on the first edition of Blatty’s novel, a nod to its success and the audience’s familiarity with it. “The title itself came directly from the novel that Blatty wrote and the text style was Weiss Initials,” says Perri.

“Relative to putting it on the screen we all felt it had to be red. But dealing with red at all on film is always difficult because it’s so intense, the colour is so raw. When it’s exposed against black it tends to, what’s called, bloom. It swells, it glows, it’s very hard to control. I had to do a lot of exposure tests just to get the right red that wouldn’t bloom. Then the typography could do its job and convey its subtleties in the letters.”

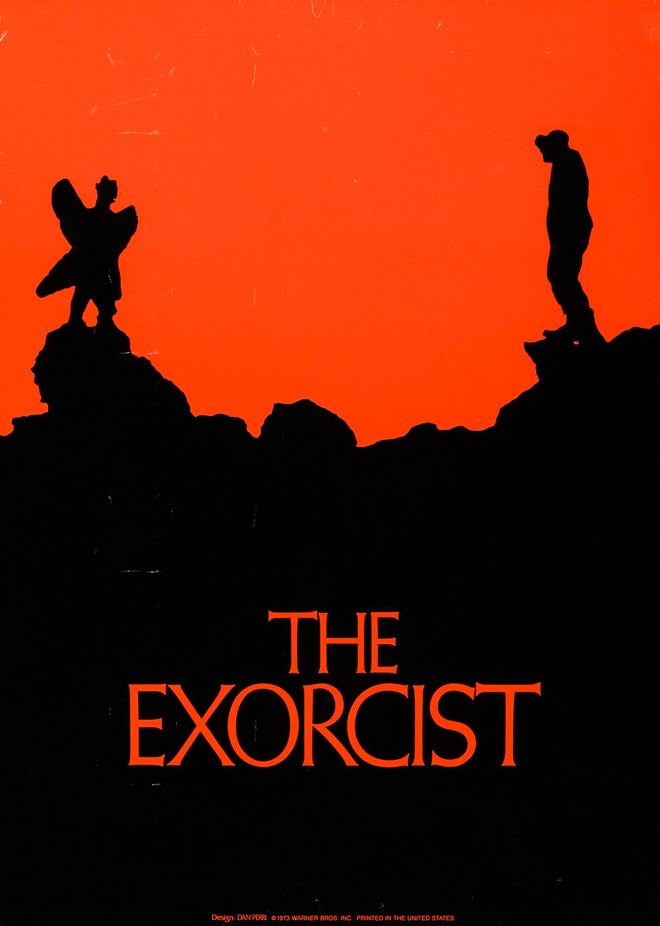

Perri’s work extended to the ad campaign for the film as well as a now-rare promotional poster.

Promotional poster for The Exorcist designed by Dan Perri

The campaign would take the film’s atmosphere, in which Perri was now deeply embedded, and translate it into a series of graphics and images that would introduce audiences to the world and mood of the film. This decision created a more detailed and focused ad campaign that few films had in those days.

“Along with the ad campaign I also did a teaser poster that was meant to be distributed around the world prior to the release of the film. The images from the film, one of Merrin in Northern Iraq while he’s on the dig standing on a cliff and across from him, on another rock, is this sinister statue. A good half of the poster is black and it says The Exorcist, that’s all. That went out in six languages and they gave me the translation in each language and I set the type in the same style and I fortunately was able to supervise the printing – silk screened rather than lithography – and printed thousands of each and they were distributed around the world.”

I think the point is to make us despair

Writing in 1976 for Film Comment, critic Robin Wood established much of the framework that would influence the analysis and writing about contemporary horror films. In his article “Return of the Repressed” from 1976, Wood wrote, "Five recurrent motifs (frequently interlinked) dominate the American (or American-influenced) horror film from the early ’60s to the present: the schizophrenic personality, cannibalism, Satanism, the monstrous child and the revenge of nature."

Still from The Exorcist

The Exorcist contains several of these motifs which helps to explain the film’s powerful impact. As Wood says of the devil himself: "The devil has traditionally been civilization’s image for the repressed (but ultimately irrepressible – like Dracula he is never really destroyed) energies, regarded as 'evil' so that they can be disowned." The opening of the film is mysterious and disorienting. From the Gothic architecture of the Georgetown home to the blistering sun of the Northern Iraq dig site, Friedkin introduces the viewer to two locations with an unclear connection.

Still from The Exorcist's opening showing a home in Georgetown

Still from The Exorcist's opening scenes set in Northern Iraq

By keeping the same Iraq prologue Blatty wrote in his novel (scenes a lesser film would have cut to get to the main attraction) and keeping Merrin out of sight until the final act after his introduction, The Exorcist plays with expectations. The film asks its audience to hold ideas, timelines, and locations on the other side of the world in mind. The importance of these varied narratives of the main characters in the film allows The Exorcist to extend the battle between good and evil beyond a family home in Georgetown, Washington and reveal the demons that lurk all around us.

Read more about Friedkin's shoot in Iraq in the Wall Street Journal:

At Home in Mosul, Mr. Fakhri Recalls an Exorcist's Visit to Iraq

Under his own steam, Friedkin traveled to Iraq to shoot the opening sequence with actor Max Von Sydow. He was only allowed to shoot if he gave filmmaking lessons to locals. Warner Brothers was dubious that he would return at all due to the turmoil in the region.

The Iraq opening at first seems at odds with the trend of horror “coming home” to Western residences, suburbs and cities which began with films like Rosemary’s Baby (1968) and Night of the Living Dead (1969). The Iraq prologue opens up the world of the film creating a narrative where the man of faith is also a man of science and research (as demonstrated by Merrin’s work on the excavation site) and how the seemingly small series of events that lead him to encounter the statue of Pazuzu shakes him to his core.

In utilizing these elements from Blatty’s novel, Friedkin builds a depiction of an evil that is eternal. It is the kind of evil Wood would have regarded as repressed – both literally, as the Pazuzu amulet which begins Merrin’s journey was buried under ruins, and metaphorically, as the demon comes to represent the greatest fears of the main characters (Chris’s fear of losing her daughter and Karras’s guilt over the death of his mother). In his 1979 essay “An Introduction to the American Horror Film,” from his book American Nightmare: Essays on the Horror Film, Wood elaborated on his thoughts on the repressed to include the idea of the Other:

“Closely linked to the concept of repression – indeed, truly inseparable from it… [is] the concept of the ‘other.’ Otherness represents that which bourgeois ideology cannot recognize or accept but must deal with in one of two ways: either by rejecting it and if possible annihilating it, or by rendering it safe and assimilating it, converting it as far as possible into a replica of itself.”

While The Exorcist remains an iconic film, it is also a film rooted in faith and the return of the good (AKA “normal”) to cast out the evil (AKA “abnormal”). The film tells its story in a way that renders it realistic; a fully realized New Hollywood version of the ancient tale of good versus evil.

Still from The Exorcist showing Father Merrin holding a rosary

Blatty’s succinct and unflinching writing (featuring shades of his personal Christian beliefs) and Friedkin’s documentary filmmaking style create an emotional response, still inspiring audiences to question how much of what they are seeing is real. The Exorcist is a truly singular film that not even multiple prequels, sequels or a television show could truly capture the spirit of. It tapped into the zeitgeist of the 1970s and a cultural subconscious swarming with moral and physical panic of a world that, in light of events such as the Watergate scandal and the Vietnam War, was becoming a scarier and less trusting place.

The abrupt cut on the title of The Exorcist and the change in music immediately subverts expectations, setting up a film that will keep its audience guessing throughout the narrative that follows multiple characters all on their own journeys who converge to save a life. The shifting plot set up in the first moments of the film establishes the lengths to which evil will go to reach us and how seemingly minor moments can lead to the biggest battles.

Director of Photography: Owen Roizman

Title Designer: Dan Perri