Part two of our exclusive two-part feature on the opening title sequences for Hulk (2003) and The Incredible Hulk (2008). This week we interview Kyle Cooper, title designer for Louis Leterrier’s The Incredible Hulk.

Kyle Cooper’s opening title sequence for The Incredible Hulk depicts Dr. David Banner putting himself in harm’s way with a few well done visual quotes from the original series’ opening. The diaphanous daughter, Betty Ross, is bloodied and a hectoring General Ross is loosed.

After graduating from Yale, Kyle Cooper began at R/Greenberg Associates in New York and eventually relocated to Los Angeles, acting as RGA/LA’s creative director. He went on to found Imaginary Forces (a result of a transfer of ownership of RGA/LA) in 1996 and later Prologue Films in 2003. His title design credits include Dawn of the Dead (2004), the Spider-Man films, The Island of Dr. Moreau, Se7en, Braveheart, and a number of the Metal Gear Solid installments.

A discussion with Creative Director KYLE COOPER.

How did you initially become involved with The Incredible Hulk?

Kyle Cooper: Well, I hadn’t worked with Director Louis Leterrier before, but I have worked with Marvel quite a bit. I designed the Marvel logo comic animation with Avi Arad, and I designed all three Spider-Man titles. Our company, Prologue, also created titles and VFX for Iron Man. In addition, I knew Gale Anne Hurd, who was a producer on both Hulk films, so they called me in at the outset. We met with Marvel and discussed the challenges. Louis had shot several different openings. In one alternative, for example, Edward Norton was up on a mountaintop, consumed with guilt for having hurt Betty Ross, and planning to shoot himself in order to keep others safe.

Cooper-designed Marvel logo

The initial idea for the opening was to create a prologue that included Banner’s backstory. It was an idea that I liked quite a bit. In fact, one of the two reasons I called my second company Prologue is that I feel if a title sequence is done well, it can often serve as the first scene, or as a prologue to the story you are about to see. Studios quite often have test screenings and realize that a prologue is needed and call us. I took the names of both my companies, Imaginary Forces, and Prologue, from the prologue of Shakespeare’s Henry V. So the idea of laying the groundwork for the story which is about to follow is something that I have always been interested in – in literature as well as film. The title sequence can create an introduction or relay the back story of a film. Condense the film’s themes and the characters’ obsessions is an interesting challenge.

For the Hulk, the primary goal was to tell the origin story in a prologue, rather than spending time on the expository during the film as Ang Lee had done. We approached the problem in various ways. We tried creating a prologue, and having the credit sequence at the end. We tried having some credits mixed with the prologue, and the rest at the end. Ultimately, I proposed integrating the credits fully into an opening that would serve as the main title as well as encapsulating Banner’s story.

I knew it was a lot to ask. Oftentimes if a director puts the credits at the end of a film, then he will just have a simple presenter card with the main title at the front. But for Hulk, we needed another element – a separate sequence to set up the story. In the past, test screening audiences have sometimes indicated that they were not clear on certain aspects of a film that could have been explained in a prologue. And yet, most of the time integrating or inter-cutting the credits with a prologue is not considered. It is often assumed that this approach would end up trying to convey too much information – that reading the credits demands a certain amount of time, and that trying to tell a story while this is happening would generate confusion. But I always say, “Let us try.” And I did that here. So I directed a second shoot with soldiers kicking lab doors down, looking for Bruce Banner, searching for clues, and discovering experiments left behind in old motel rooms long since abandoned. We generated a lot of great footage from the shoot which ultimately enabled us to tell the story in a concise and engaging way.

So how much of the production footage was already shot and brought to you and how much did you create?

We did use some footage provided by Marvel, but they didn’t just bring it to us and say, “Here, use this.” Normally I ask for what I need. I go through all the outtakes and dailies. Then I request the footage I am interested in working with and start to edit with that. Sometimes we can do a second unit shoot to fill in where the sequence is lacking, but often this is not possible due to budget concerns. It just depends on the project. For Hulk, we were lucky enough to have both.

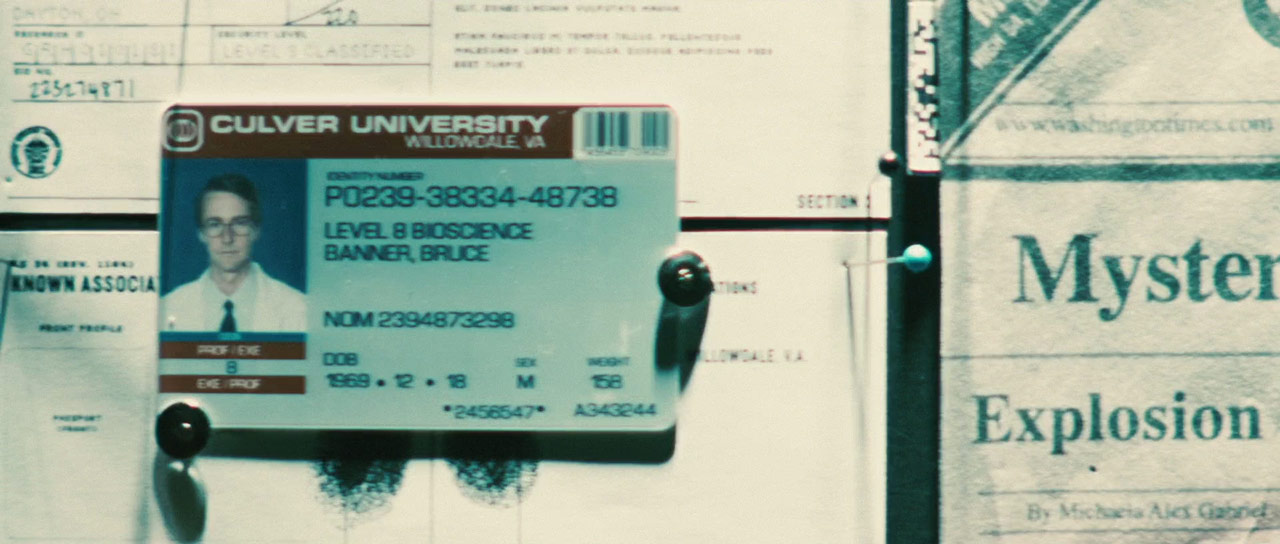

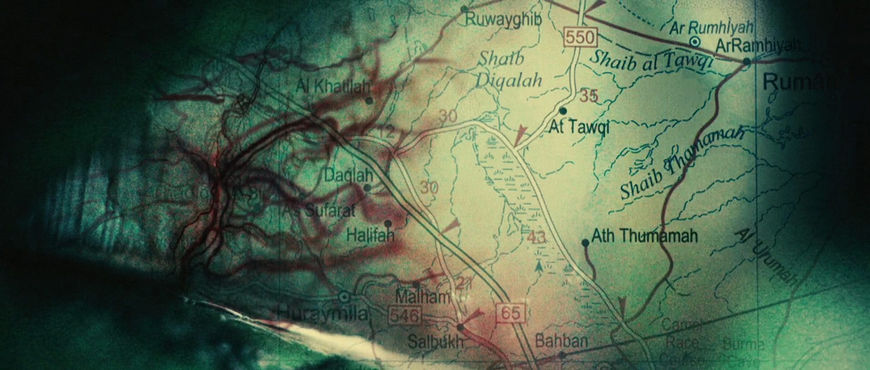

In the final sequence, there are shots of General Ross looking at the maps and smoking a cigar. There are shots that were turned into surveillance footage, as well as a wall of photographs and information being studied by General Ross. It’s all about the hunt: where he’s been, what he’s done. In many ways the sequence follows the path of the Hulk’s destruction around the globe from Ross’s perspective – Banner becomes the Hulk, hurts Betty, and the hunt is on with Ross following close behind.

"Surveillance wall" examples

So the wall we built essentially became the documentation of that hunt. The central element was a large map where Ross had tracked all the sightings of the Hulk, and stemming out from these locations were all the materials collected from that location. We spent a lot of time on research for this section, looking for images of destruction, rage, fear; looking for and creating images that would suggest the presence of something that was no longer there. We wanted to create the feeling that you had always just missed the moment – that you were always one step behind, one moment too late; leaving you with nothing but the aftermath. A destroyed pick-up truck, a blurry image from a CCTV camera, the dusty remains of a homemade laboratory. We created all kinds of medical reports and police records. We generated a full background report on each of the Hulk’s known associates, then linked them together on the wall, showing how all the connections were interwoven.

We didn’t just want to create the illusion of a large-scale wall with endless amounts of data and images. We could have done that by generating small-scale setups for each shot. But we wanted it to be real, so we built it fullscale. And in fact, we had to rebuild it several times over the course of the project, photographing it extensively during the development of the sequence, and then doing the final build on set for the shoot.

The scene in the hospital, on the other hand, was shot by the director, but it wasn’t put together as a sequence – it was just raw footage. A lot of what I wind up doing is editing and figuring out how to simplify. Initially, they had shot an origin scene, which they had cut a number of different ways, but it was long and the story wasn’t clear enough. It did prove to be a good foundation, however, so we essentially began with that and developed the story from there.

In fact, the television show with Bill Bixby also had an origin story in the opening credits and I think Louis felt that the approach was an interesting one. Although I don’t want to speak for him, I think some of what they shot tipped its cap to that original opening, and nicely so: Banner being in the chair, doing experiments, Betty looking through the glass, and, of course, the transformation. But they didn’t want to reveal too much of him in that scene, just as we hadn’t wanted to show him clearly in the images of the hunt. They didn’t want to give him away before the movie even started. So we had to come up with ways of getting around that – ways of showing the Hulk without revealing too much.

TV show open comparisons

We filmed high-speed close-ups of shirts ripping and seams coming apart. We used the camera to shoot close-ups of teeth, to follow veins down an arm or inside an eyeball, then used those veins as a way of transitioning into lines on the map, always hinting, always working to heighten the sense of urgency and mystery without being too explicit. We even worked on an over-the-shoulder shot of the Hulk standing up from his chair, shot from the Hulk’s POV and using an effect to create the Hulk-vision similar to the old TV show.

Did you start out with a list of elements or ideas from past Hulk stories that you wanted to use?

I do a lot of research. I had not read The Hulk in a number of years but I read the comics a lot when I was growing up. I had all The Hulk comics, and the entire first set of The Hulk and Submariner comics, so I certainly knew the story. I was kind of a hardcore Marvel Universe guy. Growing up, my brother and I had 6000 comics. We even had The Amazing Spider-Man #1 but my mother threw it away because she would do that if we left them out on the floor. She also would not let us watch The Three Stooges – you know how mothers are. I loved the Hulk, I loved the Fantastic Four, and I feel lucky that they have all come back to me working on these projects.

But for a comic, as with any main title, the first stage is always research. I read the script. I find out everything I can. I listen to the director and watch the movie. Then I try to figure out how to best answer the brief. We wanted to get right into the movie by telling the origin story in the credit sequence, and yet the story we needed to tell was extremely important. I didn’t want to walk into this with the attitude that we just needed to get the origin story out of the way fast so the real movie could start. I wanted it to be an essential part of the film, to add another layer of meaning to the overall script. Everyone thought it would be a very difficult thing to do. In fact, I was really surprised at the number of people who wrote about the title sequence online and in the press. I actually put a lot of those quotes on our website because it was wild to me how many people mentioned that the origin story was done in the opening credits. I didn’t understand why that struck people. To me, it always seemed possible. And more than that, it seemed natural. It always just seemed like the right thing to do, although looking back, I guess it was a challenge.

I went to the first Hulk premiere with Garson who was the title designer for that film. Garson and I are old friends. We went to school together, and I hired him at R/Greenberg Associates in New York. I had met with Ang Lee about doing the first film, but Garson got the project that time. The two movies had some of the same producers, but they didn’t want to do it the same way, so I ended up doing the titles this time around.

Spider-Man 3 title frames

You’ve also done the titles for the Spider-Man films. Is there anything about doing a superhero film that is different from any other? Is your approach any different?

I don’t think the process is any different. The tendency is to lean more towards something illustrative or animated. It is a different problem to solve, but I don’t approach it any differently. I like doing comics. I loved working on Spider-Man. There is a need to set up the story each time, to tell the audience where they are and what has happened before, although the first Spider-Man was a bit of an exception. For the first film we had more of a blank canvas, which enabled us to play more freely, coming up with visual metaphors and ideas that did not have to be tied to a narrative. I liked the idea of type being caught in a web and so that became a form of typographic wordplay that we used throughout. But in each of the subsequent films we had to tell the story of what happened in the last episode, so again, the opening turned into a prologue, setting the stage for the next chapter in the story.

When did Craig Armstrong’s theme music come in? Did you have access from the start?

When we first began doing editorial sketches, we did not have the music. We started by cutting to temp music and as we progressed, Craig provided us with different pieces. He kept refining the music, making it better, and so we would modify the edit to his music as it developed.

This goes differently every time. Sometimes we get a piece of music like we did on Mission: Impossible, where it already exists, but often I pick the music I want to cut to and offer my opinion to the composer. Sometimes the rights to the music used in the edit are obtained, but it can be a lengthy process. The composer is generally very proprietary about the title score, and prefers the opening to be his own music.

How do you work with members of the production team, in terms of participation? How many people worked on this sequence?

There’s always someone who has to lead the team. For this project it was me. But people collaborate on different levels. There are animators, there are editors. Sometimes I’ll have more than one editor trying different things. For The Incredible Hulk there were two editors, at least three animators, and a full crew for the live action shoot. The team at Prologue built props for the shoot and everyone kind of rallied around the project.

For most films or commercials it seems like there is a team. I know these days you can have a one-man band, where a single designer can do his own boards, his own typography, can shoot his own footage and even do his own animation. But usually we have to work fast and having a team allows you to have each person dedicated to one thing. For myself, I’m usually working on a couple of things at once and function more like a director, which is what I really enjoy most.

Shirt tear moment

What are some of your favorite elements from this sequence? You use live action, typography as well as still imagery, a whole range of media. It seems to have most of what you like working with.

Everything but the kitchen sink? Yeah. Sergei Eisenstein talks about the “immutable fragment of actual reality.” It’s like breaking reality down into all its pieces and thinking about each frame as a singular composition – and each element within the composition of that frame as a separate entity as well. You can break it down that far.

I try to go through each sequence frame by frame and not have any frames, or any sequences of frames, that I think are poorly color-corrected or composed. So to answer your question – what did I like best about this Hulk? Well, for the image gallery on our website I went through the sequence frame-by-frame and pulled the ones I liked the best. There are a couple of frames that could be made better, but the ones that I like are the ones I picked for the website. There is one frame that you cannot even see when it’s running in real time; a moment in which the seam of the Hulk’s shirt is tearing. I like the color correction on it. I like the composition. I think it’s beautiful even though it is depicting a violent moment. So that is an element I think is good even though you hardly see it. I also like the skeleton of Edward Norton’s face, just before the Hulk credit comes up. I like moments like that where you are seeing many things at once, many layers coming together to create a whole.

Veins to map frame

You mentioned filming eye veins and maps earlier, and that image really stood out when going through the end of the sequence frame-by-frame prior to this call.

Thank you for reminding me of that! That would be the next one I would mention. I really like the idea of the veins of an eye becoming a map – he’s changing, but he’s also running away. It’s a very short moment, but as a frame, and as an idea, I really like it. It’s well composed. It’s beautiful, and it tells the story in a very quick and concise way. So those kinds of frames – those kinds of little details – perfection is made up of trifles. I’m not saying it’s perfect, but those kinds of trifles are interesting to me.

To have perfect moments within?

Yes, and that’s maybe the argument for going through frame-by-frame. On the other hand, even if every frame is beautiful, if the animation isn’t choreographed in an interesting way or if it is not interesting to watch, but rather just a series of good-looking frames – then it will not transcend the sum of its parts and become something more. There are so many choices. There is so much stock, and so many elements, and so many stills, and so many key frames. There is so much stuff going on in the sequence, in the office, in my life, I have to ask myself, “What do I do right now?” And the answer always seems to be, “Just focus on one little, small thing first.”

SUPPLEMENTAL: Original TV show open