After back-to-back masterpieces Sullivan’s Travels and The Lady Eve, director and screenwriter Preston Sturges pulled off a comedy trifecta in 1942 with The Palm Beach Story. At this time, there was still a tradition, inherited from live theatre, of titles that simply presented a programme, with the director, producer, cast, and crew listed in some appropriate typography on an appropriate background, backed by some appropriate theme music. All very static, all very much what the folks taking their seats expected.

The Palm Beach Story’s title sequence is something very different: a fast-paced mystery prologue in pantomime, propelled by a breathless mash-up of the “William Tell Overture” and the “Wedding March”. Given the classical theatre convention that comedies end in marriage, this could easily be the finale of a prequel to the film we’re about to see – a bride and groom racing separately to the altar in taxis, overcoming perils along the way, the breakneck action punctuated by freeze-frame shots.

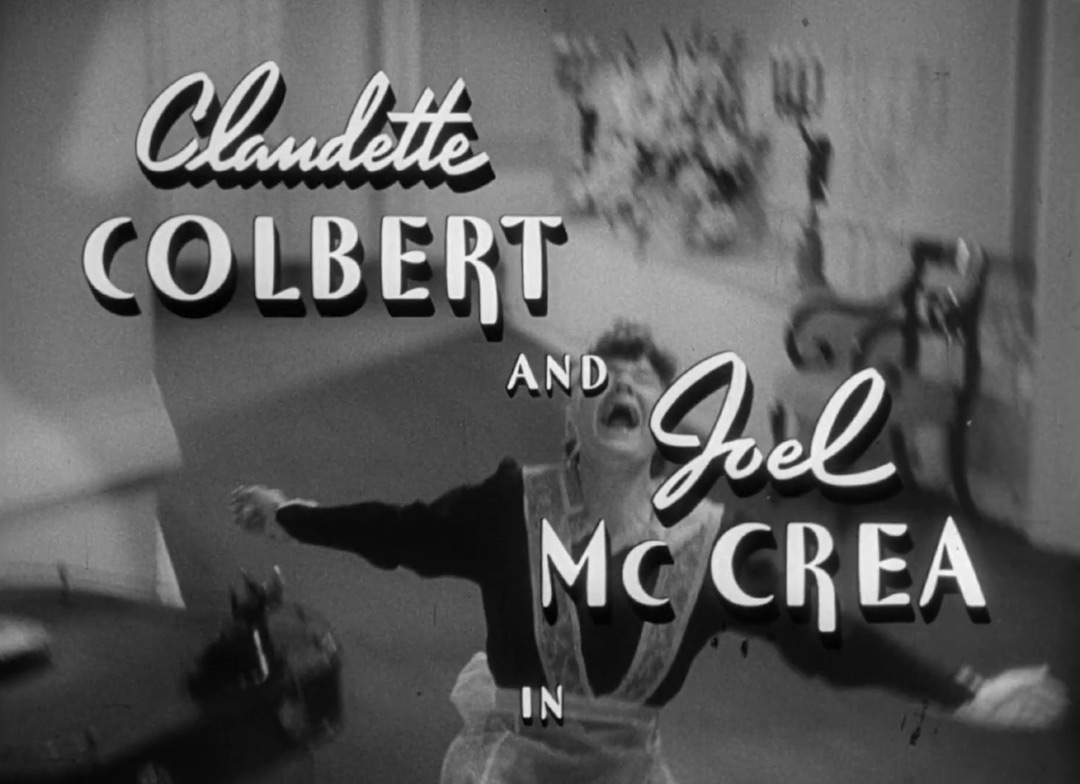

As soon as the Paramount logo fades, we are plunged right into the story: a lady’s maid, telephone in hand, jabbers at someone off-screen – then shrieks in panic and falls into a ludicrously dramatic faint at the sight of a looming shadow. Over the first freeze frame, of her collapsing backwards onto the floor, we see the names of stars Claudette Colbert and Joel McCrea.

After a quick shot of a church filled with guests, the clergyman nervously looking at his watch, we cut to McCrea’s character and some groomsmen, all in formal dress, frantically tumbling from the canopied entrance of a tony apartment building into a taxi. As McCrea stabs a finger back at the doorway, shouting, he is frozen mid-gesticulation and the main title appears.

Next, we see the shapely legs and satin undergarments of a woman, apparently Colbert, whose face is mostly hidden by the scarf used to gag her; she is locked in a closet, her hands are tied, and she’s frantically trying to kick her way out. Is she even really Colbert? The next shot clearly shows us the star – in a gown and veil that evoke her runaway bride in It Happened One Night – glancing back at that closet door and then freeze-framed as she dashes out of the room, the movie’s supporting cast superimposed over a cloud of tulle and orange blossoms. And what a cast it is! Mary Astor (playing a comic twist on her man-eating femme fatale), Rudy Vallee (then a faded teen idol getting a career renaissance with this role), and Sturges stalwarts William Demarest, Franklin Pangborn, Chester Conklin and Roscoe Ates (seriously, they don’t name actors like they used to).

Freeze frame of Claudette Colbert hailing a cab in bridal garb

Colbert dashes out of the room – to a lovely flute motif suggesting the delicacy of her lace train as it trails over the prostrate maid – into the street, where she hails a cab in her bridal garb. Her upraised arm is frozen mid-air, and we see more credits; one, appropriately, “Miss Colbert’s Gowns by… Irene”. In an exquisite touch, when Colbert unfreezes, her movements are sped up momentarily so that her impatient bounces look as if her kitten-heeled pumps are on tiny springs.

By the time McCrea and then Colbert come rushing into the church, shedding a top hat and some flowers in their madcap dash into the camera, we are no clearer about the shadowy figure, the locked-up lady, and the look-alike Colberts than we were before. As the bridal couple kneel before the minister, the title sequence ends with one last superimposed text, in the form of an elaborate doily: “And they lived happily ever after… or did they…?” The film proper begins, but we’ll have to wait until literally the last minute to know what its mystery prologue really meant.

One thing's for sure, questions about the wedded state will be a major theme; in fact, the movie’s working title, nixed by the censors, was Is Marriage Necessary? – a question which the four-times-wed Sturges certainly must have asked himself.

Elaborate hand lettering on glass

A year before The Palm Beach Story, freeze frames were featured prominently in the hit comedy Hellzapoppin’ (one of the most enjoyably wacky movies ever made); in the early 1940s, they were still a novelty, and Sturges’ repeated use of them in this title sequence surely struck the film’s first audiences as a signifier of zany times ahead. Nowadays audiences have different expectations because they were raised on freeze frames, whether as a trope in 1970s television (look at all the series whose episodes always ended on one, from Rockford Files to Wonder Woman), or in the films of directors like Martin Scorsese. However, in cinema freeze frames are not usually associated with laughs anymore, but with death: think of the finales of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Gallipoli, or Thelma and Louise.

The reason for this shift in the use of effects like freeze frames or speed-ups could be that cinematic comedy today is not, generally speaking, as visually inventive as drama (with notable exceptions, like the work of Edgar Wright). But to be really funny, Sturges is telling us in this wordless opening salvo, a movie should also look fun. And The Palm Beach Story certainly does, cementing its writer-director’s enduring reputation as the patron saint of screwball.

Supplementary: The Palm Beach Story end titles

Bonus! Watch the original trailer:

Supplementary: The Palm Beach Story (1942) trailer

Title Designer: Uncredited

Music by: Victor Young

LIKE THIS FEATURE?