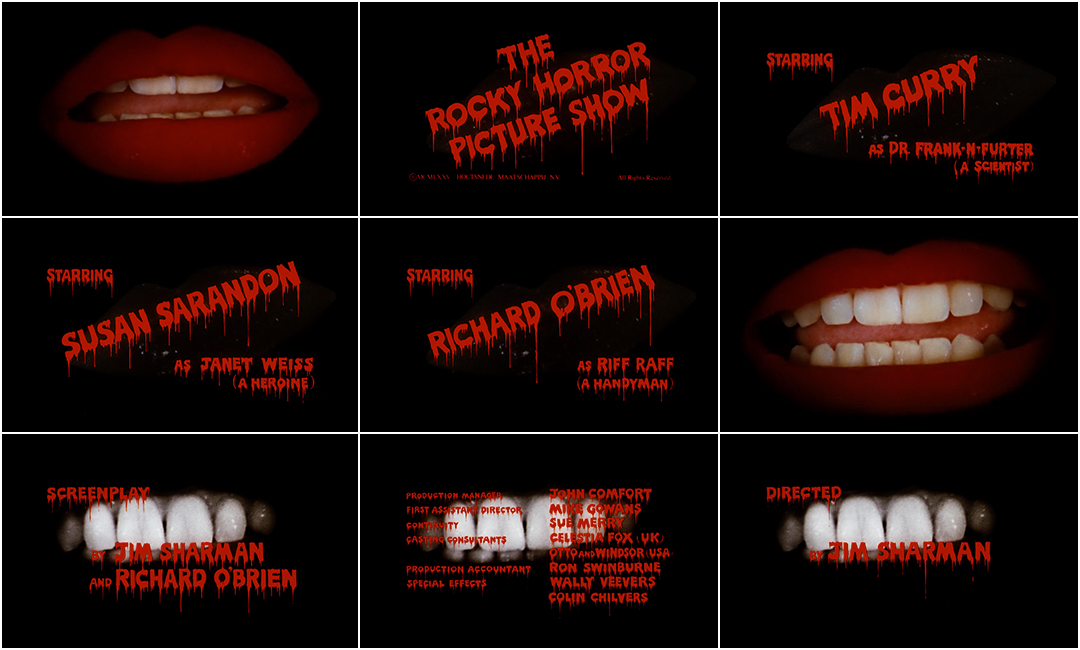

As a stripped-down version of the Twentieth Century Fox theme plays, a midnight screening of The Rocky Horror Picture Show begins. "And God said, Let there be lips!" And there were lips: red lips, white teeth, black background. An androgynous voice sings “Science fiction, double feature.” Between verses, the lips freeze in black and white before fading into a cross above a church.

If it were not for expensive usage rights and the studio’s inability to secure Shirley Bassey-level talent, these unforgettable ruby-red lips, singing a song with someone else’s voice, might never have come to be. An iconic and blustering introduction to one of cinema's greatest cult films, the opening credits to The Rocky Horror Picture Show set the tone for the film's punk energy and playfully paradoxical atmosphere.

The ruby-red lips that sing "Science Fiction, Double Feature" during the opening titles of The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975)

The Rocky Horror Picture Show, now one of the most successful cult films of all time, began as a stage play. Originally titled They Came from Denton High, it was written by Richard O'Brien while he was a broke actor trying to find work in London and intended as an homage to the science fiction B-movies he loved as a child.

The original stage play, initially entitled They Came From Denton High, also starred Tim Curry as Dr. Frank-n-Furter.

Against the backdrop of the emerging glam scene in the U.K., O'Brien would throw in a dash of rockabilly and an ironic sense of humour. In the play, the car of a square, newly-engaged couple breaks down during a rainstorm. Welcomed into the strange and beguiling castle of Dr. Frank-n-Furter, they find their boundaries challenged and their universe expanded.

O'Brien showed an unfinished version to Australian theatre director Jim Sharman. Throughout the 1960s, Sharman had made a name for himself as an important director of experimental theatre in Australia. In 1972, he directed a self-funded film called Shirley Thompson vs. the Aliens. While difficult to track down in full, the film's clips reveal its wry, post-modern tone. Writing about a clip available on the Australian Screen official site, critic Richard Kuipers describes the film's subversion of suburban conformity, saying:

"The scene shows a lively mix of influences. The setting recalls British kitchen sink realist dramas of the 1950s and '60s; Rita talking directly to camera echoes a technique employed by many French New Wave directors. A thick layer of melodrama and black humour is added [...]"

Sharman was an obvious match for the anti-conformist bent of O'Brien's writing; they shared similar influences and a dark sense of humour. The production began as a small experimental piece but gained traction and other collaborators like set designer Brian Thomson, costume designer Sue Blane and actress Patricia Quinn.

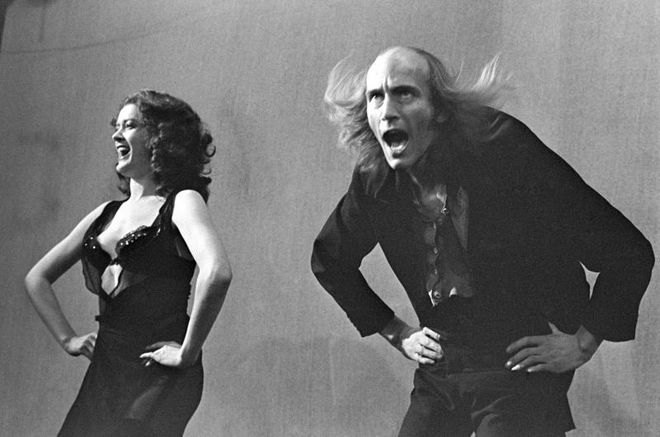

Patricia Quinn as Magenta and Richard O'Brien as Riff Raff do the Time Warp in the stage play The Rocky Horror Show, 1973

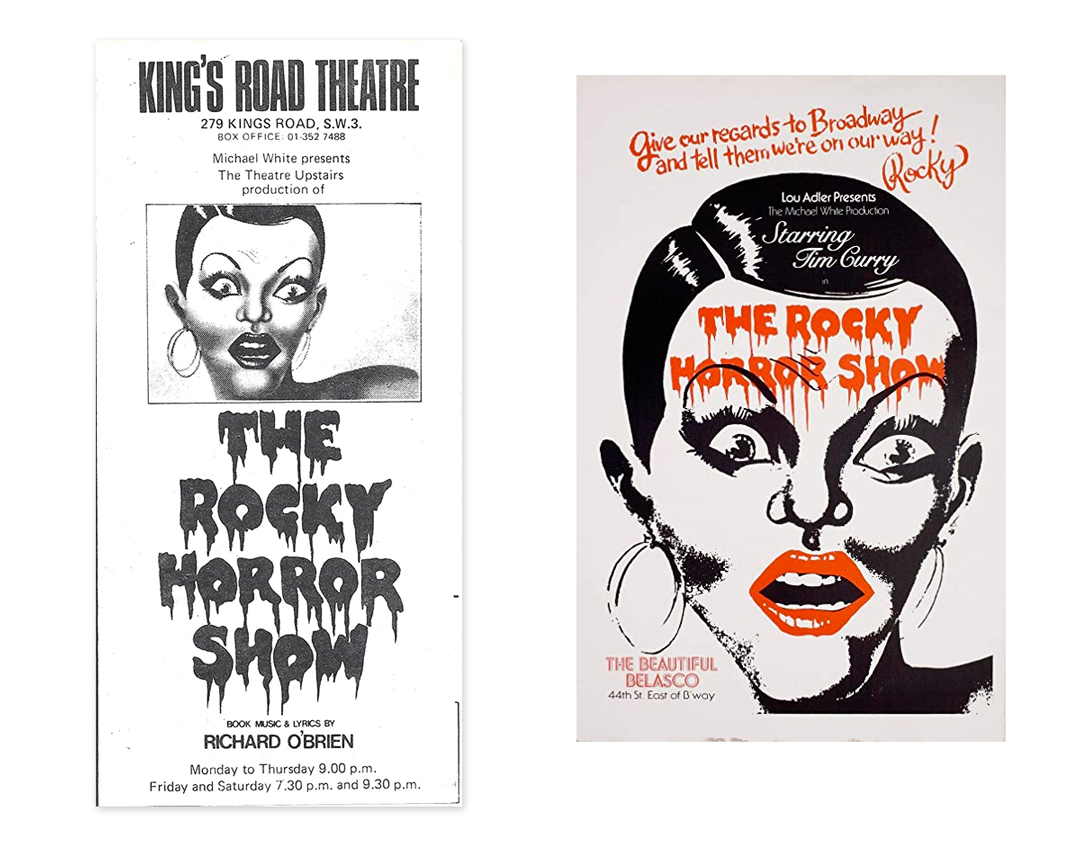

While it started in the smaller London theatres, it grew in popularity, eventually finding a home at the 500-seat King's Road Theatre in November 1973, where it ran for six years. The musical made its U.S. debut in Los Angeles in 1974 before being played in New York City and other cities.

Cover of an original programme from the King's Road Theatre production in London, where it played from November 3, 1973 through March 31, 1979 (left) and a poster advertising the show at the Belasco Theater in New York City, where it ran for 45 performances in 1975 (right).

Seeing the stage production’s success, Twentieth Century picked up the rights and O'Brien set to work adapting it for the screen. In the stage production, the opening song “Science Fiction Double Feature” was sung by a character called The Usherette. She was played by Patricia Quinn, who also played Magenta on both stage and screen. For the big-screen treatment, however, O'Brien wanted to pay homage to the song's influences by opening the film with a montage of classic monster movie clips. In the script, he selected not only the films to be included but specific scenes or shots as well.

Patricia Quinn as Magenta and Richard O'Brien as Riff Raff in The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975)

With that change in the opening, the filmmakers also wanted a different singer. Patricia Quinn had revealed in many interviews that she almost turned down the film when she realized she would not get to sing “Science Fiction Double Feature,” her favourite song in the musical. She was only convinced to play, as she tells it, after producer John Goldstone brought her to see the sets. At that point, she was eager to start and, unbeknownst to her, she would still get her shot at singing “Science Fiction.”

Brad and Janet (top left) watch as convention attendees do the Time Warp

Actress Patricia Quinn as Magenta in The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975)

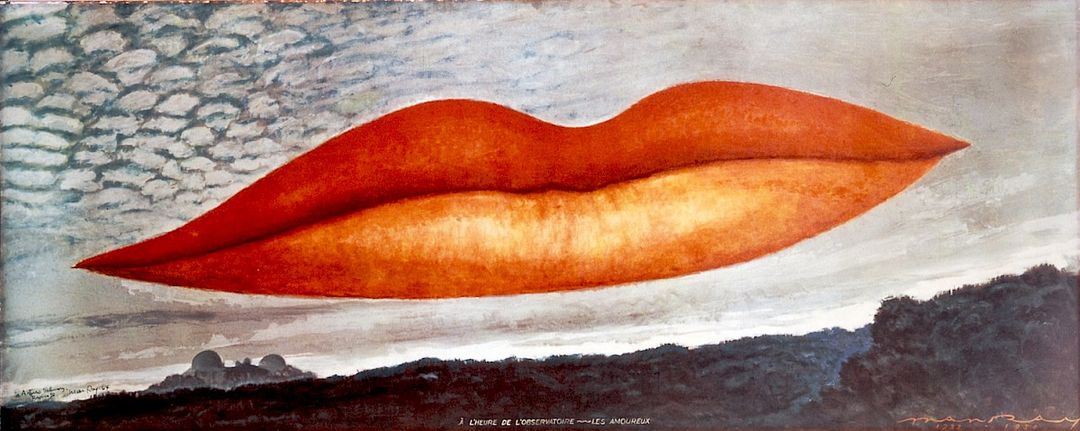

Producers quickly realized that O'Brien's opening clip show would be prohibitively expensive and another solution needed to be found. At this point, set designer Brian Thomson had an idea. Inspired by the Man Ray painting Observatory Time: The Lovers (better known as The Lips, 1936), he imagined a close-up of a pair of lips singing the theme song.

The painting "Observatory Time - The Lovers," is often called simply "The Lips," was created by artist Man Ray from 1932 to 1934.

The connection with the work of Man Ray has substantial thematic implications. As a painter and photographer, Ray is best known for his work that toyed with the perception of bodies. The Lovers recontextualizes an organic shape and subverts and amplifies its sexual power. The lips on the horizon take on the simultaneous role of God and Monster. Like an apparition from another world, they inspire both fear and reverence.

Another point of reference was Samuel Beckett's play Not I, which was presented in 1973 at the Royal Court House in London. In the play, actress Billie Whitelaw plays "the mouth." The stage was completely dark except for a spotlight that illuminated Whitelaw's lips eight feet above the stage. The rest of her body was cloaked in black material and gauze so only her mouth was visible.

A segment from the BBC Two video "A Wake For Sam" in which actress Billie Whitelaw introduces her 14-minute performance of the Samuel Beckett play "Not I" at the Royal Court in London, 1973

The images of the production are remarkable for the intensity of the idea and for its resemblance to what would become Rocky Horror's opening.

Billie Whitelaw during rehearsal for Not I in 1973, seated with her head between rostrum clamps to steady her head. She would then be cloaked in black, creating an image of a mouth floating in darkness.

Photo by Zoë Dominic

Most accounts seem to agree that the lips in Rocky Horror were shot on one of the last days of production. As Quinn tells it, she was approached at the last minute to ask if she'd be the lips. She was still under the impression that the studio would hire a big star to redub the song. "Someone like Shirley Bassey," she said. It was at this point she was told that it would be Richard O'Brien singing, a kind of homage to his authorship. She harboured resentment but it was finally a way for her to get back her favourite song, even if it wouldn't be her voice.

Immediately, though, the crew ran into technical problems. In an interview for Australian TV, Quinn explains:

"They blacked out my face; then they drew the lips. Then they put me on camera. When you sing, you move, so the mouth kept going out of frame. So, they screwed my head into the lamp thing so I couldn't move."

As Quinn says the words "lamp thing," she gestures to suggest barn doors, often used to control lighting. While this was seemingly uncomfortable for Quinn, she says it didn't take long to shoot as she knew the song well. Also, having worked with O'Brien for a long time, she had an idea of his particular gestures, contributing to the almost seamless relationship between her movements and his voice.

In his book, Punk Slash! Musicals: Tracking Slip-Sync on Film, David Laderman introduces the idea of Slip-Sync:

"Slip-sync hinges upon the more mainstream performance technique of lip-synch. But in slip-sync, the singer-performer slips out of sync, alienated from yet caught up by the performance spectacle. Rupturing lip-synch from within, slip-sync articulates both resistance (the singer refusing, or unable, to be synchronized) and conformity (the sound track, or the performance spectacle subsuming the performer)."

The Rocky Horror Picture Show becomes a big point of discussion in his work, as one of the most significant examples of the technique — most of it focused on the discordant and iconic opening sequence.

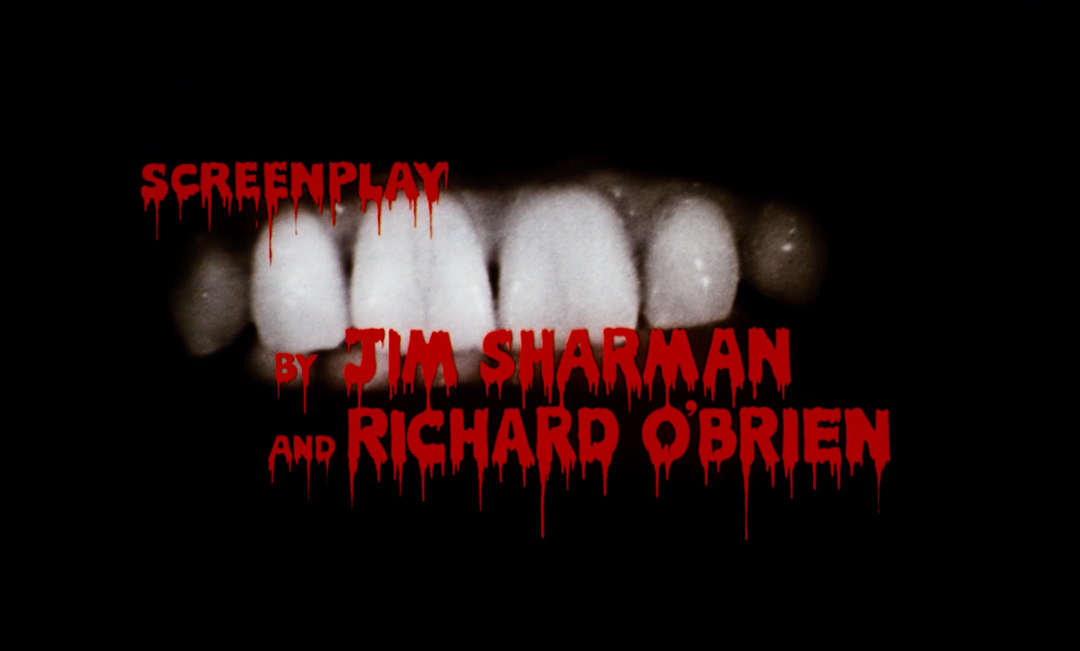

"Screenplay by" credit dripping with blood on top of a black-and-white rendition of Patricia Quinn's teeth and lips

Referencing the film's hodgepodge of references and strange temporal shifts (aka Time Warps), the film fundamentally toys with the concepts of time and synchronization. Furthermore, the way it "denaturalises gender" similarly contributes to the sense that it purposefully throws convention and expectations out of sync. He writes:

The Rolling Stones band logo was created by designer John Pasche in 1970. Read more in How the ‘Greatest Rock and Roll Band in the World’ Got Its Logo

"Perhaps deliberately evoking a similar, early 1970s Rolling Stones icon, these provocatively androgynous lips fill the screen in tight close-up, prefiguring slip-sync in several ways. First, they are disembodied, lips without a face, floating like some giant sea creature against a black void. More to the point, the singing lips slip out of synch ever so slightly. [Jeffrey Andrew] Weinstock notes the tension between Richard O'Brien's ‘particularly plaintive’ and ‘thin tenor voice,’ and Patricia Quinn's ‘lascivious red lips,’ which ‘disguise’ this voice. In this way, the sequence intimates a gap or separation between voice and body, one that, anticipating punk, problematizes traditional gender as well as traditional synchronization in film."

The effect not only anticipates the gender-bending of the film itself but sets a tone of destabilization. Rocky Horror Picture Show's familiar unfamiliarity tears down conventions as represented by Brad and Janet, turning everything slightly askew.

Janet, Brad and Dr. Frank-n-Furter seen through the crook of Rocky's flexed bicep

Tim Curry as Dr. Frank-n-Furter as seen through the elevator gate

The lyrics to “Science Fiction Picture Show” also serve as an annotation for the film's various references. Rocky Horror fans like James M. Curran have worked hard to deconstruct the possible meanings and allusions of the different film moments, connecting them to the film. Many of the movies referenced are produced by studios Fox and RKO (both of which are referenced within the film). Originally as part of the floor show and the performance of "Don't Dream it, Be It,” they planned for the set to include an art deco Fox fanfare logo but this was scrapped in favour of the RKO tower.

Rocky, Janet, Dr. Frank-n-Furter (center), Brad and Columbia dance in front of an RKO tower stage set in The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975)

Yet Richard Hartley and the band had already recorded a new version of the Twentieth Century Fox theme that they'd end up using in the opening credits, one of the first times that the Fox theme was changed or not used entirely. It seems that Fox was reluctant to have their brand associated with the strange movie and similarly scrapped an idea that would have both Magenta (Patricia Quinn) and Riff-Raff (Richard O’Brien) manipulating pulleys to move the spotlights in the Twentieth Century Fox logo.

The other important elements of the credits are the typography and the bleeding letters. More than a reference to a specific title, the effect evokes the "shock" trailers associated with science fiction and horror B-movies of the 1950s in particular.

The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975) main title card

In trailers that warn audiences to "Prepare to be shocked!" the typography is distressed, often connoting danger and movement. While not exactly blood, many older credits or posters like those for Dracula or Frankenstein employ expressive font choices to signal the horror or monstrosity that lies ahead. Because the production aesthetic was already established, its title graphics grew out of existing marketing material, maintaining the bloody brand. Post-Rocky Horror, there are more examples of the blood effect used in posters for films like Wolfen (1981), Basket Case (1982) and Chopping Mall (1986), though their title sequences, notably, feature very little blood.

Posters for the films Wolfen (1981), Basket Case (1982), and Chopping Mall (1986), all featuring blood-dripping typography

While the Rocky Horror Picture Show film was considered a flop upon its release, it developed a dedicated fan base through its cult midnight screenings. Rather than fading into the dark corners of oblivion, it swiftly became a huge cultural reference point and Patricia Quinn’s lips are now among the most famous in film history. Only the haunting close-up of Orson Welles’ mustachioed upper lip whispering “Rosebud” in Citizen Kane evokes the same iconographic status. Rocky Horror also echoes title sequences like Vertigo (1958), Repulsion (1965), and Seconds (1966) in its use of intimate close-ups of the human face to disorient and set the tone for the rest of the film.

Seconds (1966) main titles, designed by Saul Bass and Elaine Bass

The opening sequence of Rocky Horror, brandished and echoed in the poster art, has similarly come to represent the most cultish elements involved. A precursor to punk and a startling homage to camp sensibilities of the past, Rocky Horror's subversive energy still resonates today. Both of its time and beyond it, the film's credit sequence plays no small part in its continuing cult status.

The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975) end titles

Title Sequences by: Camera Effects Ltd.

Lips: Patricia Quinn

Music: "Science Fiction Double Feature"

Written by Richard O'Brien

Performed by Richard O'Brien