The visionary and essential novelist Toni Morrison was born on February 18th, 1931 and died on August 5, 2019. In between, she was a voice of great power and resounding truth, a celebrated writer and editor, a recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom and a Nobel Prize winner, a mother of two and a teacher of millions.

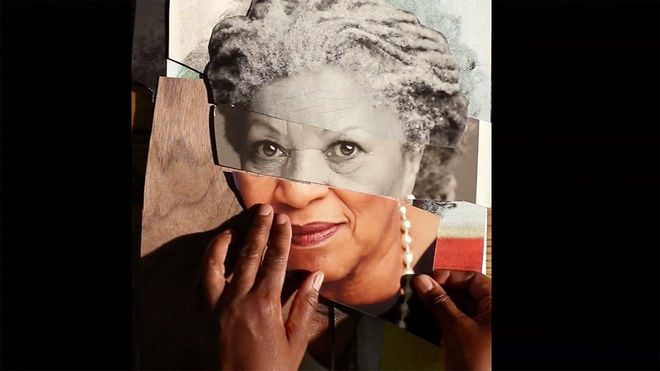

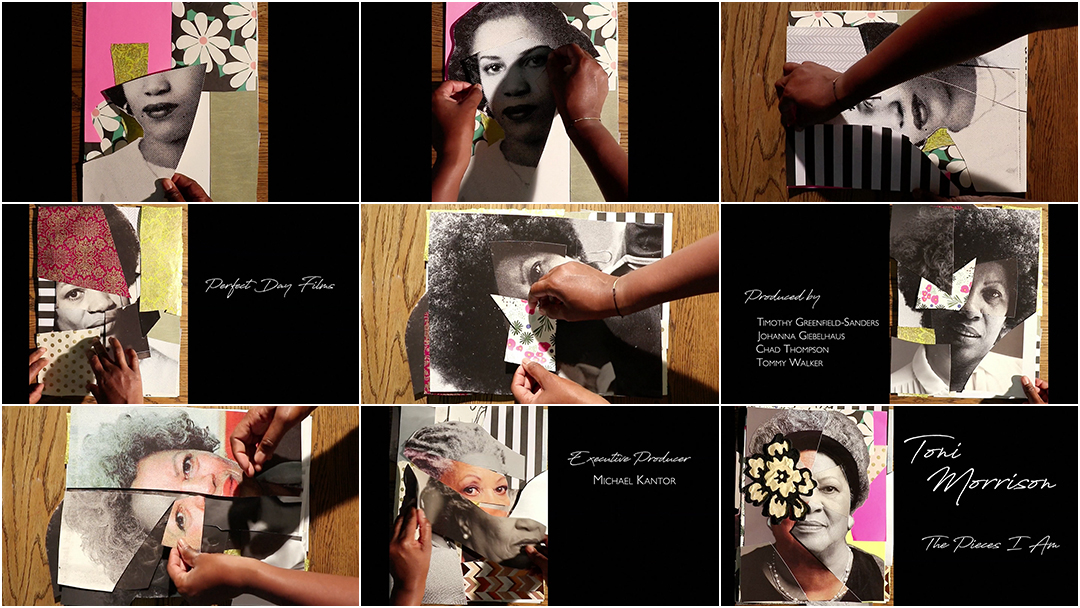

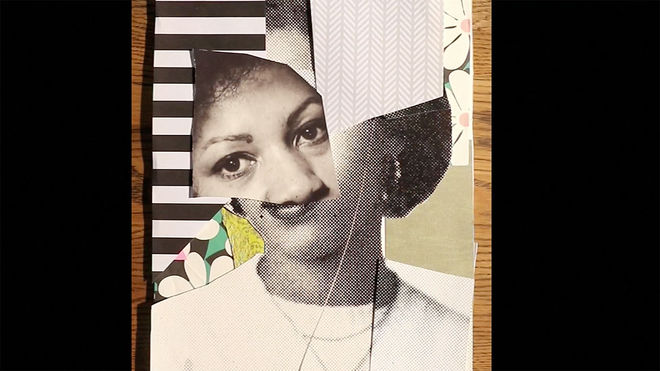

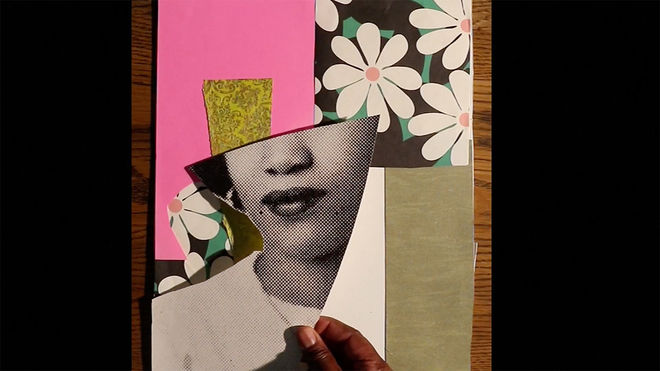

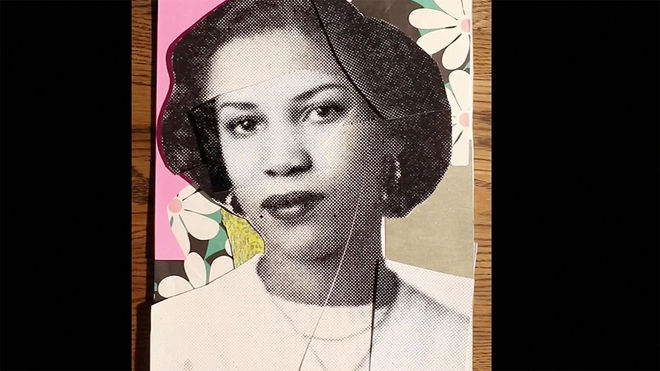

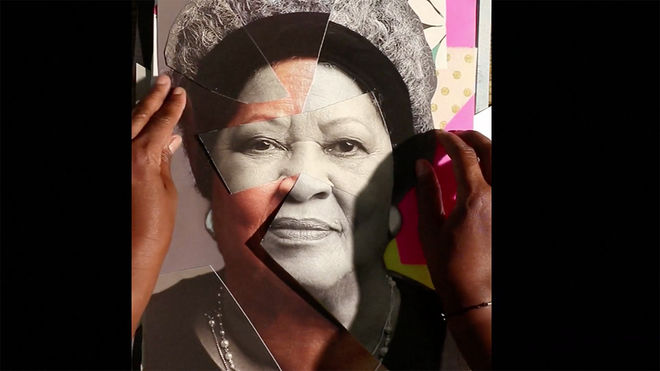

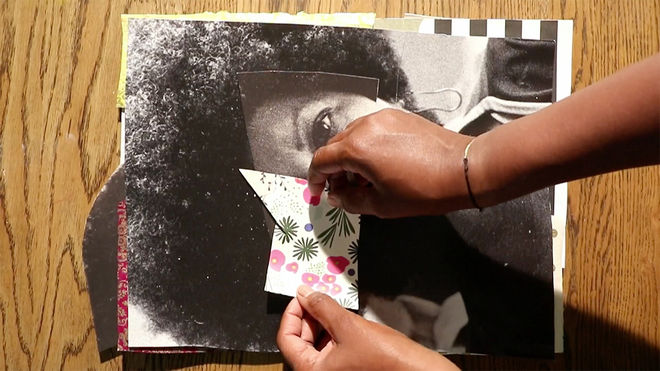

It is her powerful voice that carries us through director Timothy Greenfield-Sanders’ sweeping and intimate documentary Toni Morrison: The Pieces I Am. “She is a friend of my mind,” says Morrison in the opening moments, reading from Beloved, her 1987 Pulitzer Prize-winning novel. “She gather me, man. The pieces I am. She gather them and give them back to me in all the right order.” Her voice is soft and warm and smooth, the cadence measured and even, inviting us into her extraordinary life. We watch as a pair of hands assembles irregular shards of photographs and patterned paper, a scrapbook portrait built, piece by piece, upon itself. The hands belong to Brooklyn-based Mickalene Thomas, a mixed-media artist whose work often takes shape through painting, collage, photography, and video and draws on culture, history, and themes of sexuality, beauty, and power.

Mickalene Thomas in her studio.

Photo by Les Guzman for Upstate Diary (issue 8). Used with permission.

In the opening sequence, Thomas physically gathers pieces of Toni Morrison which include photographs created by Greenfield-Sanders as well as others and arranges them into a shifting video portrait. The opening recalls the style of Morrison’s 1974 nonfiction project The Black Book, “a lavishly illustrated scrapbook spanning three centuries of African-American history, reproducing newspaper clippings, photographs, advertisements, handbills and the like.”

Read the New York Times' obituary, written by Margalit Fox:

Toni Morrison, Towering Novelist of the Black Experience, Dies at 88

The footage of Thomas’s collage assembly is beautifully buttressed by Kathryn Bostic’s lilting and contemplative jazz score, joined with credits designed by Declan Zimmermann and Perpetual Motion Graphics, and made whole through cuts and rotations by the film’s editor and producer Johanna Giebelhaus.

It’s an astounding opening, a prelude that takes Morrison’s words literally and continues her work championing Black artists and voices. It also gorgeously sets the stage not just for Morrison to speak candidly but also for her friends and colleagues Hilton Als, Angela Davis, Oprah Winfrey, Fran Lebowitz, and others to share their memories and thoughts. The film goes to great lengths to create a sense of craft, ease and intimacy between subject and viewer and it all begins right here, in the opening titles.

Director Timothy Greenfield-Sanders and Producer and Editor Johanna Geibelhaus discuss working with Toni Morrison and the challenges of distilling her remarkable life for film.

A discussion with Director TIMOTHY GREENFIELD-SANDERS and Producer and Editor JOHANNA GIEBELHAUS.

Timothy, you had a relationship with Toni Morrison that spanned decades. How did you first meet?

TGS: I first met Toni Morrison 38 years ago, in the winter of 1981, when she came to my East Village studio for a Soho Weekly News cover portrait. She wore a dark suit with a white blouse and smoked a pipe.

—Timothy Greenfield-SandersHers was a monumental life that has impacted the world’s culture, a life that deserved an important documentary.

Toni Morrison in 1981.

Photos by Timothy Greenfield-Sanders

TGS: I was a young photographer and Toni had just finished her fourth novel, Tar Baby. I was impressed by her confidence on the set. Toni liked my work and we became friends… and I eventually became her photographer of choice, for book jackets, publicity photos and the like. Her trust in me began way back then.

Toni Morrison and members of the documentary crew. Clockwise from left: Chad Thompson, Johanna Giebelhaus, Jackie Sanchez, Graham Willoughby, Leon Coltrane, Tommy Walker, Sandra Guzman, Toni Morrison, Timothy Greenfield-Sanders.

Photo by Timothy Greenfield-Sanders

How and when did you begin work on this documentary?

TGS: I’ve wanted to make a documentary about Toni since we worked together on my documentary series The Black List that aired on HBO in 2008. Toni was the first person to sit for that film and she was just so compelling in front of the camera. In 2014, I approached her about making a documentary about her life. At this point, Toni was world famous but quite private. She had always said that she wouldn't write a memoir or authorize a biography. She was reluctant to talk about herself and hesitant about the hours required for filmed interviews. But she didn’t say no. I explained how important I thought it would be to hear from her friends and colleagues and to capture on film her history, accomplishments and the important themes of her many works. Hers was a monumental life that has impacted the world’s culture, a life that deserved an important documentary. It was also a film I really wanted to make. Eventually, Toni agreed.

Johanna, how did you become involved? This is your second collaboration together, right?

JG: It’s my second collaboration with Timothy, yeah. The first film that I worked with him on was The Trans List, that was the most recent installment of his List film series. I edited that.

TGS: She had come highly recommended by my long-time producing partner Tommy Walker. For The Trans List, Johanna showed a sensitivity to the material that I admired. When it came time to put together the team for Toni Morrison: The Pieces I Am, I was very conscious of what Toni describes as “the white male gaze.” I very much wanted to assemble a team that didn’t look like me so I would have different perspectives and opinions helping to shape the film. Johanna’s passion for the project and her understanding of Toni and Toni's work made me certain that she was the right person to edit this film.

JG: There was a lot of trust that started with Toni Morrison’s trust of Timothy, and then Timothy’s trust of me, and then that trust extended to Kathryn Bostic and Mickalene Thomas... As a team, there was a lot of creativity and trust and inspiration.

TGS: Johanna is a stellar editor. She is thorough, creative, collaborative and passionate. However, her talents go far beyond the edit suite. She was also the lead researcher on the film and one of our producers.

So, Johanna, you wore a number of hats on this production. Tell me about the different roles that you embodied.

JG: Yes! [laughs] I’m a producer on the film and I’m the editor. I did all the research – at Princeton, in the Random House archives, in Toni Morrison’s personal archives. She was incredibly generous in giving us access to her personal archives. So I did the archival research, the thematic research as well as the visual research, compiling images that needed to accompany the film.

TGS: She traveled to Lorain, Ohio to research Toni’s childhood and family and even shot Super 8 footage of Toni’s childhood home there. She combed through the archives at Princeton and Columbia that house Toni’s papers.

JG: I also wore the hat of the music supervisor and doing the research on the music that would be in the film in addition to working with Kathryn Bostic, who is an incredible composer. She did a tremendous score. The music that you hear in the opening is hers. She scored to picture after I had edited the title sequence.

Documentaries don’t often have special opening titles like this. How did you approach the titles?

JG: The opening title sequence really is special. It’s something that we’re all proud of and certainly, watching it now after Toni’s passing, it has even more meaning and emotion to it. The artwork in the collage was by the extraordinary artist Mickalene Thomas. Some of her other paintings are in the film.

An overhead view of the desk of Mickalene Thomas featuring pieces of collage, including the artwork for Toni Morrison: The Pieces I Am.

Photo by Les Guzman for Upstate Diary (issue 8). Used with permission.

The opening emerged from the editing, quite late in the game. We didn’t have the title locked down. We weren’t sure about the title. We weren’t sure exactly what the opening would be. It emerged from thinking about artwork and figuring out a way where artwork could be a part of honouring Toni from the beginning, but also being an entry point for the film.

Let’s start with the photographs. Timothy, as well as directing films, you’re also a photographer. What does photography mean for you as a filmmaker and how is it part of your process?

TGS: In my years as a fine art photographer, I’ve photographed everyone from presidents to Oscar winners. I understand the importance of putting someone at ease in front of the camera, whether I’m shooting a portrait or filming an interview. For each of my films, I photograph all of the interviewees in the film. So photographing Fran Lebowitz, Hilton Als, Oprah Winfrey, et cetera, was no different than what I’ve done for my other films. Generally I photograph everyone immediately after the interview has taken place. This is when they’re at their most relaxed and we've had time to develop that trust that’s important between a photographer and his subject.

Toni Morrison on set for the documentary, 2016.

Photo by Timothy Greenfield-Sanders

JG: The set itself is always quite an intimate space. That’s something he’s really gifted at – creating an environment where his subjects feel really comfortable. It’s always a nice way to end the experience, too, taking a portrait.

TGS: Often these portraits become the spine of the opening credits. We knew early on that we wanted to incorporate my portraits of Toni and we needed a format that allowed us to see these. For this film, because I had photographed Toni over the course of 38 years, we had so many images to choose from in creating the opening.

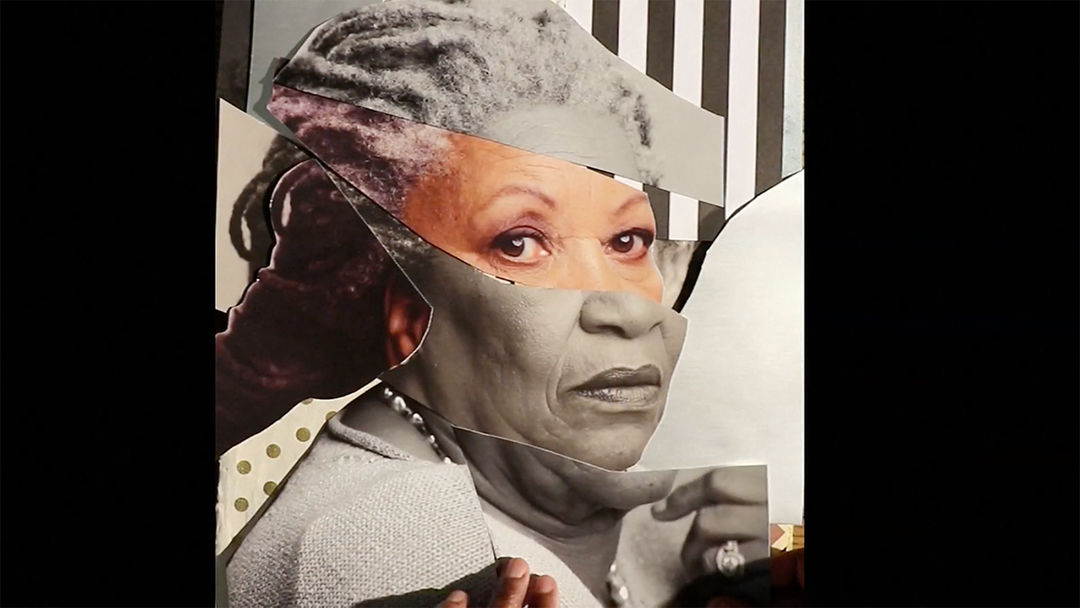

JG: In Mickalene’s opening collage, I think there are 10 portraits of Toni that Mickalene used and six of them are Timothy’s portraits. The last portrait of Toni, at the end, is also his portrait. I think the first one is her high school graduation photo, so she’s 18, and the last one she’s 87.

So you see Toni emerge through eight decades. Mickalene’s collage is very moving and it encapsulates what we experience in the film. The film is gathering the pieces of Toni to tell her story.

And the end credits, that is a part of Timothy’s style, as well. I think nearly every film of his, the end credits sequence always features portraits he’s taken of the interviewees.

Still from the end credits featuring a portrait of Angela Davis taken by Timothy Greenfield-Sanders

VIDEO: End credits sequence (featuring photography by film director Timothy Greenfield-Sanders) and crawl

Still from the end credits featuring a portrait of Hilton Als taken by Timothy Greenfield-Sanders

How did you choose Mickalene Thomas to work with on the opening?

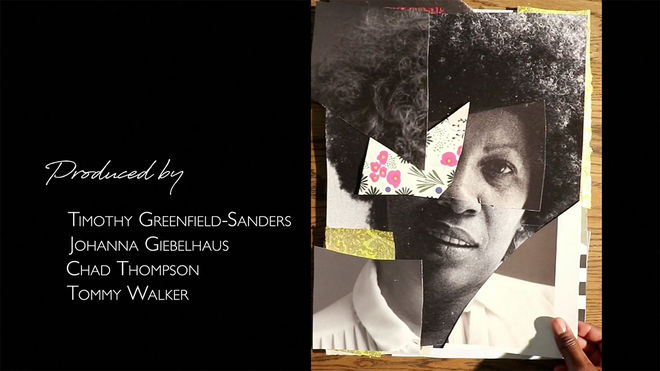

TGS: Mickalene Thomas is a world-renowned artist whose distinctive work is instantly recognizable. One of the film’s producers, Chad Thompson, first suggested her. I was very aware of her work but I had never met her. I had used a collage-type opening for my documentary About Face: Supermodels Then and Now and knew that, in the right hands, an opening collage that comes to life could be remarkable. Through my art world contacts, I tracked her down and all I had to say was “Toni Morrison” and she replied, “I’m in!” We felt Mickalene’s collages beautifully reflect Toni’s style of writing – non-linear, using bits and pieces from so many sources, and magical. We all love what Mickalene did and we love her!

Mickalene Thomas in her studio.

Photo by Les Guzman for Upstate Diary (issue 8). Used with permission.

JG: We’re incredibly grateful that she agreed. Her own body of work is so important as an artist, as a contemporary artist, as an African American woman. None of us knew exactly what it was going to be but we were all thinking about collage and this idea of fragments. I think I gave her hundreds of images of Toni. Mickalene worked for several months and then she gave me raw video. She filmed herself making her collage of Toni’s portraits.

That is Mickalene working, putting the collage together. The video that she gave me was just the raw footage of her working. It was all one position, the horizontal landscape position, filling the screen. I spent time thinking about how that would work. I edited it and this is what emerged.

I wanted to mention also the motion graphics editor I worked with, Declan Zimmerman at Perpetual Motion Graphics. Declan worked with me on the opening and he chose the fonts.

Can you talk a bit about the various artwork included in the film and the music?

JG: The artwork of the film is a really important element in the storytelling. We have almost 50 artworks by African-American artists in the film. They’re woven throughout and they accompany Toni as she’s weaving these themes together, as the film is weaving themes together.

There’s also music by incredible African-American composers, many of whom aren’t as well known, and African-American performers. Timothy and I wanted to infuse the film and surround Toni with artworks and music by African American people.

Tell me about how the film was shot and the various ways of looking. Toni is looking into the camera while the others are looking to the side.

TGS: Only Toni looks into the camera, directly addressing the viewer. Conceptually, of the film’s 13 interviewees only Toni was filmed in my direct-to-camera style. This decision allows the audience to experience an intimate one-on-one conversation with Toni. Throughout the interviews, Toni was open and intimate, thought-provoking and emotional.

Still from Toni Morisson: The Pieces I Am featuring Farah Griffin

Still from Toni Morisson: The Pieces I Am featuring Toni Morrison looking into the camera

Still from Toni Morisson: The Pieces I Am featuring Walter Mosley

JG: It comes out of Timothy’s portrait style. His filmmaking style grows from the talking portrait style. It creates a further intimacy with Toni as she’s leading us through her life. That sort of intimacy in Timothy’s style is something that I thought about in the editing, just bringing out these intimate, emotional, sensitive moments throughout the film.

And as editor, you had the monumental task of cutting down all this material. Essentially, an entire life. Was that a daunting process?

JG: It is daunting! Toni was incredibly prolific, not only in her writing but she had a generous and active public life for five decades, not to mention her work at Random House as an editor. She edited books, she wrote books, she taught books. Hilton Als, in the film, says it’s hard to get your head around someone who did so much and then he quotes Toni, saying, well, she had a life in books. She also was a single mother supporting her household and raising two sons. So there’s just a vast amount of material. The way I approached it editorially was really around themes. That was a way to start an initial organization of the content and storytelling. That was very much research-driven and driven by the incredible interviews that we had – and Toni herself. She led us through.

If you had to estimate the number of hours of footage, how much would that be?

JG: There’s a lot of still material but we were approaching almost 80 hours of footage, with everything. For Toni’s interviews, we had about six days of material with her.

Toni has a particular cadence and rhythm to her speech. How did you work with that and how did you find the rhythm of the film?

JG: Her rhythm and cadence is absolutely beautiful. When we were listening to her in interviews, it was just transformative. Toni reads all of her own novels and audiobooks; it’s really important to her that the rhythm and cadence and the delivery of language is honoured. She’s very particular about how her language is delivered. So I was very aware of that and wanted to honour that. I was very aware of her pauses. I wanted to preserve that space in her language but also find ways to create spaces visually in the film, where we as viewers can have time to process and to think and to go with her. To have room for evocative moments. It became a tool in the visual storytelling.

VIDEO: Trailer for Toni Morrison: The Pieces I Am

Building a rhythm in biographical films is always a challenge, keeping things moving. It really became an experience of figuring out how to weave the pieces together, much like a quilt. A quilt was my model or metaphor from the beginning, because that’s very much a form of Toni’s writing itself. Many of her novels jump through time, in and out, so I had that in my mind as an editor, thinking about how we do that. Keep it moving forward and keep it interesting and also having some places to go on little side journeys.

And how did you work with composer Kathryn Bostic?

JG: Working with Kathryn Bostic was a gift, it really was. We clicked personally and professionally. She’s a huge Toni Morrison fan. I had been experimenting with some music and had a temp track built. We started experimenting with keys and we settled on the palette of jazz. You hear the muted trumpet quite a bit – that really became Toni’s theme. The voice of Toni on some level. Also a rootsy palette. There was a real synergy in working together and trying things.

And getting back to your question about rhythm, you hear the upright bass – that was something that worked really well with Toni, as she’s speaking. It’s a very supportive sound but it also gives you space. Toni herself, in her language, is an instrument, so we wanted to support that.

Last question. Timothy, what does Toni Morrison’s work mean to you?

TGS: Early in the film, Toni says she learned early on in life that “words have power.” Her writing has impacted so many people around the world… to heal, to imagine, to develop their own voices. Toni was a pioneer. Her ascent to the literary canon was a significant breakthrough that allowed other women and African Americans to be seen and heard. As we’ve taken the film out to theaters across the country, I’ve been able to see the depth of gratitude for Toni's words.