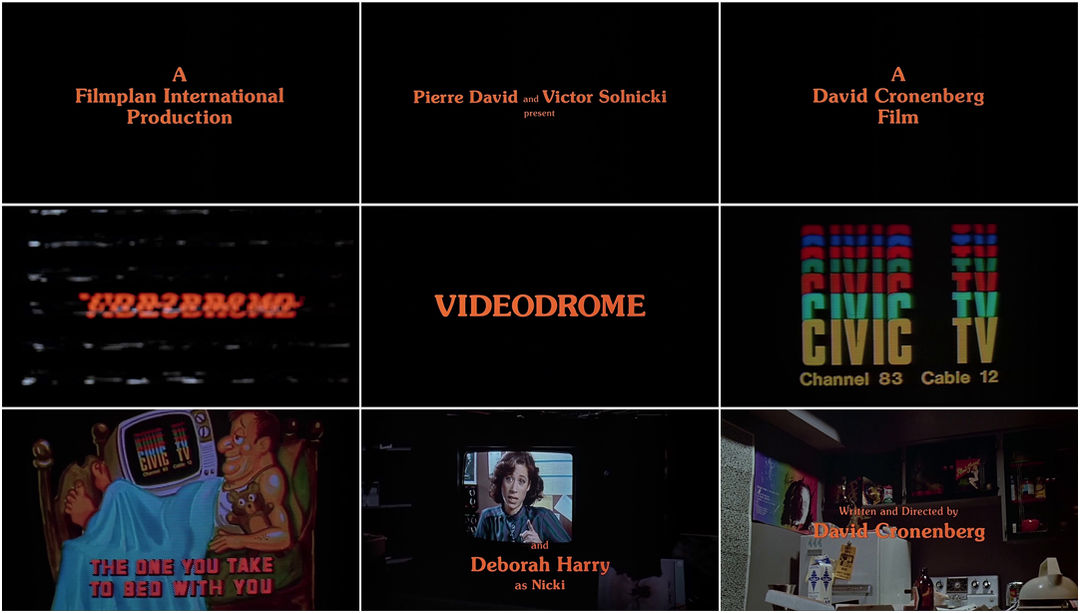

Director David Cronenberg’s 1983 film Videodrome is a hallucinatory meditation on the future of television; a malignant love letter to the power – and danger – of mass media, delivered to viewers as only he can, in the trappings of a genre picture. Videodrome also happens to feature one of the most thoroughly effective opening sequences of Cronenberg’s long career, an opener that would foreshadow the Canadian filmmaker’s frequent and authoritative use of title design to set the stage in subsequent works.

Arriving with a hiss, bent and distorted, Videodrome’s bright orange title card coalesces in a storm of static, giving way to a TV station ident: "CIVIC-TV (Channel 83, Cable 12) … THE ONE YOU TAKE TO BED WITH YOU." The cheerful message is accompanied by the image of a lonely man lying in bed with his television, a teddy bear tucked beneath his hairy arm. These opening moments will tell viewers most of what they need to know about Max Renn (James Woods), the film’s main character – a pioneering television impresario and purveyor of schlock and shock. Renn’s faithful executive assistant Bridey James (without whom it is evident he is completely hopeless) then appears on screen to deliver his docket for Wednesday the 23rd. Month and year unknown.

Animation of the Videodrome title card.

The personalized video wake-up call, busy schedule, and elaborate watch reveal that Renn is a man of means, but as the camera tracks through his apartment the viewer sees that he lives in a sort of affected squalor. Lit and warmed by a cathode ray tube, the only of object of importance in this gloomy, cluttered abode is the television. Like the man in the station ident, Renn goes to bed with CIVIC-TV every night; unlike the man, Renn sleeps on the couch and in his clothes. No teddy bear in sight. Successfully roused by the TV message, a freshly showered Renn dines on a breakfast of coffee and cold pizza. It’s here, chuckling at his kitchen counter, that Renn gets his first glimpse of Samurai Dreams, the bizarre and racist porno movie that sets the events of the film in motion.

But let’s go back to the start. Composer Howard Shore’s dark, electronic score gives Videodrome a foreboding edge right from the get-go, playing over the normally grandiose Universal fanfare. Though overriding the studio bumper is a fairly common practice today, it was an unusual way to kick off a film in the early 1980s. Composed for an orchestra, Shore recorded both a classical arrangement of the soundtrack and a completely digital version programmed into a Synclavier II synthesizer – mixing between the two throughout the film. The latter gradually becomes the more dominant sound as Renn descends further and further into signal-induced madness.

The CITY-TV channel ident compared to the CIVIC-TV channel ident from Videodrome.

Despite the largely American cast, Videodrome is a Canadian film to its core. The setting and even some of the characters will be familiar to anyone from Toronto, Cronenberg’s hometown and backdrop for the action. Renn’s CIVIC-TV is inspired by the real-life CITY-TV, an upstart UHF channel infamous for broadcasting violent midnight movies and softcore pornography in its early days; his colleague Moses a reference to CITY co-founder Moses Znaimer. However, the increasingly nightmarish goings-on might feel familiar to viewers in other ways. Though Videodrome preceded the Internet age by more than a decade, Cronenberg’s film presents an eerily prescient vision of the future – a world where ceaseless stimulation and untold perversity and depravity are just a screen and a few button presses away, on demand, all the time. Cancer guns and killing sprees notwithstanding, Renn’s excitement for – and feverish pursuit of – overstimulation (be it torture or titillation) seems almost pedestrian in light of our own current clickbait, multi-tab, instant gratification culture. Long live the new flesh, indeed.

Supplementary: Videodrome's original theatrical trailer

Titles by: Film Opticals

SUPPORT ART OF THE TITLE